Quentin S. Crisp is not Quentin Crisp. For a long time I thought they were the same person. Perhaps you can guess why. In any event, this mistaken assumption led me to also believe, for some years, that the collection of horror stories by Quentin S. Crisp called Morbid Tales and published by Tartarus Press, used copies of which were priced well above what I was willing to pay, was the work of Quentin Crisp. Quentin NMI Crisp, I mean, The Naked Civil Servant and whatnot. I became very interested in Morbid Tales, and bitterly mourned my not-rich-person status. Of course, part of my interest hinged on the belief that The Naked Civil Servant had written it, because I hadn't been aware that horror fiction was anywhere close to the kind of thing he ever wrote. Now, over the course of my periodic obsession to learn more about this, certain clues should have indicated to me that this was another different Quentin Crisp altogether (why that "S" all of a sudden, for instance), most of which I won't bore you/embarrass myself by relating. But skipping ahead, an entirely affordable copy of Morbid Tales finally revealed itself to me, and I pounced (if I hadn't, I doubt it would have been available much longer). When it arrived in the mail, I turned to the introduction by Mark Samuels, which opens with this:

Sometime during 2001, Matt Cardin, a friend and correspondent of mine in the United States, suggested I contact an author then resident in Taiwan who shared our interest in the work of Thomas Ligotti. I think my first reaction was to ask whether the author's name was genuine. Doubtless those of you who have bought this book without first being in contact with its author have asked yourself the same question. So to clear up any confusion, this Quentin Crisp is a thirty-one-year-old writer and not the late Quentin Crisp, 'Professor of Style' long exiled in New York.

I have to say, I was vaguely disappointed to learn this, despite the fact that whoever had written Morbid Tales was being noticed and approved of by, as far as I was concerned, all the right people. No doubt this is why, the night the book arrived, I read two short stories, dubbed them good but uninteresting, and set the book aside. But let me, at long last, cut to the chase: Quentin S. Crisp has been publishing books since 2001, many through small specialty presses, many out of print and basically unavailable (or actually unavailable, in some cases), but in recent years has founded, or co-founded -- I don't know the details -- an excellent publishing company called Chômu Press that makes books by writers like Mark Samuels, Reggie Oliver, Michael Cisco, and plenty more, available at regular normal-person prices. And as you might expect, and as you might wish (if you're me, at least), Crisp has thrown a couple of his own books into the mix: "Remember, You're a One-Ball!", his first full-length novel (he'd previously published a stand-alone novella called Shrike through PS Publishing), and just last month a reprint of his 2009 story collection, All God's Angels, Beware!.

Earlier this year, I got over my moping over this being a different Quentin Crisp and read "Remember, You're a One-Ball!". Certain blurbs contained in the pre-book ancillary pages proved too fascinating to resist, none more so than this one, which is not a blurb but rather a "rejection from a publisher who wished to remain anonymous":

You write like a dream, Quentin, and the novel is well paced, but the subject matter is so challenging; so unremittingly inhuman, cruel and full of hatred that it is unbearable.

I'm not sure about all of that, but it was certainly cruel, it contained at least some hatred and inhumanity, and Quentin S. Crisp does, as it turns out, write like a dream. "Remember, You're a One-Ball!" also turned out to be fairly challenging, unquestionably bizarre, occasionally baffling, both sickened and sickening, despairing, sexual, morbid, melancholy, and lonely. That title doesn't refer to billiards, incidentally.

So I was somewhat primed, if not a little bit uncertain, when embarking on today's reading. In fairness to you, at the height of my beneficence, I have chosen to work from All God's Angels, Beware! rather than Morbid Tales, seeing as I snapped up the last affordable copy of that one in existence. After some research, I finally decided to go with what might be considered the centerpiece of All God's Angels, Beware!, a 70-page novella called "Ynys-y-Plag," which, I know, sounds Lovecraftian, but don't worry, it's only Welsh. Although I suppose the Lovecraftian lilt, or warble, of "Ynys-y-Plag" is probably no accident -- there is a certain Lovecraftian spike to the story itself, I suppose, though in terms of influence, two other writers stand out much more sharply: Thomas Ligotti (a Lovecraft acolyte anyway) and Arthur Machen. Machen's "The White People" in particular comes through strongly in the first half, as does Ligotti's "The Red Tower," with its total absence of any people, by which I mean any characters, only a kind of inexplicably sinister production.

But "Ynys-y-Plag" is very much its own thing, and it's something of a masterpiece, I think. It takes the form of a new introduction -- ostensibly an introduction, I should say -- to a reprint edition of our narrator's most famous book of photography. Our narrator is nameless, of course, but the story is written as if we should obviously know who he is. He's a famous and successful photographer, an artist, and the book for which he's writing this introduction, Traces, is a very well-known and sought-after collection of his work. The photographer himself, however, is ambivalent about his own talent, and rather less so about Traces:

If I can call Traces great art, and if I can also say that I dislike the work, that -- let me be frank -- I hate it, it is because in a sense it is a work that has little to do with me as an artist. It is a work, also, that I wish had nothing to do with me as a person. It was created by circumstance and a camera, and I, unfortunately, was there at the time, pushing the button.

"Ynys-y-Plag" then takes the form, as you might expect from the kind of introduction that it's pretending to be, of a "making of" account. The photographer explains the course of his career up to the point that the idea for Traces occurred to him, though he does so with a sort of bitter indifference, and how the idea for the book transformed into something else. Essentially, he'd hit on the idea of exploring parts of England and the rest of the UK with which he was unfamiliar, being an "urbanite," so he'd started putting a map on his wall, closing his eyes, and sticking a pin into the map. If the pin marked a location that was at all usable -- not in mainland Europe or in the ocean, basically -- then he would drive there, and the location would become his subject. One day, when he was ready to begin a new project, he stuck his pin into Ynys-y-Plag, a town in Wales. So that's where he went.

The first twenty to thirty pages of "Ynys-y-Plag" are very dense with descriptions of the the Welsh landscape, and the strange effect Ynys-y-Plag, the town, has on the photographer. I read a quote from Crisp where he said that his greatest strength as a writer is "description," which might seem like an awfully general thing to single out, but reading this novella I think I know what he means. Here he's describing a particular photograph of a strange dome he took in Ynys-y-Plag, one that wound up in Traces:

I still don't have a very clear idea of the purpose of the dome. A high and untrimmed hedge along one section of the main road largely obscured the dome from sight. Its round, tiled apex, however, rose about the hedge outlandishly, as if it were a flying saucer squatting on some private but poorly concealed landing pad about which no one dared enquire...When I looked upon the dome in daylight, it gave me a bleak feeling of being lost -- like a a child separated from his parents in a strange place -- and seemed a symbol of the kind of emptiness that creeps increasingly into life when you reach adulthood, casting over everything an irreversible chill that tells you there is no such place as home. However, the photograph I took in daylight somehow failed to capture this feeling, and I knew I had to come back at night. When I did, what I saw gave me a quite different feeling. Beneath jellyfish bells of sodium streetlight glare, and the blue light of the moon that made all shapes bestial and squinting, the dome seemed otherworldly. This was a stage beyond emptiness. If nature abhors a vacuum, then it seemed, looking at that dome in the crabbed and space-distorted darkness of the miserable night, that all that was left in the universe to fill the vacuum of the soul was some alien spirit whose strangeness was so potent that it could not whisper and sigh within the knowledge of a human being without intoxicating, possessing and transforming.

There's a lot of this kind of thing in "Ynys-y-Plag", and in Ynys-y-Plag. Upon entering the town, the photographer experienced a wash of uneasy feelings, including that he was trespassing just by being there at all, and that his trespass was not going unnoticed. His descriptions of his own photographs dig deeper, though still deepening the mystery. Traces most famous photograph, the one that graces the cover, is of one of the town's many bridges -- indeed, every road and path seems to lead to another bridge -- and what inspired, or rather forced, perhaps, the photographer to take that particular picture was the presence of a child's shoe. Later he finds different manholes sunk into the earth, which may lead, as you'd expect, to the sewer system, but may not. At one of these manholes, he sees a tiny sock nearby. At both manholes, he feels a terror at the very idea of turning around, though he must in order to retreat. Elsewhere, he sees a massive tree that grows up and out over a slope of ground, and over a body of water. From one of the branches hangs a swing made of a rope of blue nylon and a stick. He takes a picture of this, wanting to capture a particular stillness to the swing, and the strange light of Ynys-y-Plag's twilight, and then he meets a man. The man approaches him, and points out an otter swimming in the water behind him. As the two men begin to talk, the stranger begins to sound more and more wild as he warns:

"...There's a bug down there. Some people round here catch it sometimes...You see something strange, though, you don't look, unless you want to catch the bug...They say that sin and evil's human, but there was some kind of sin here a long time before people came. The worst time was the plague. That's when it was everywhere..."

Ynys-y-Plag, by the way, means Island of the Plague.

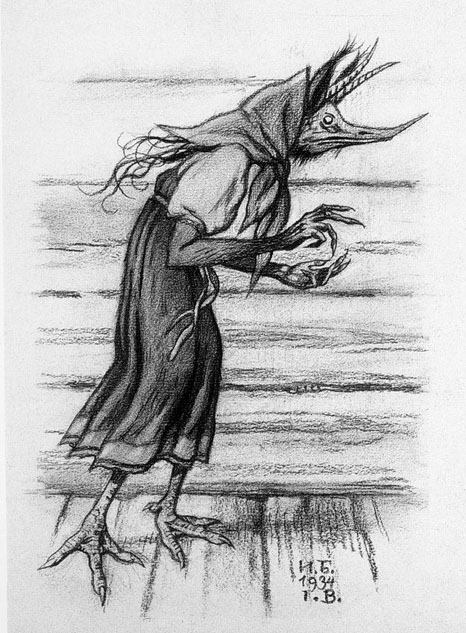

There is so much going on in this story. The plot is actually fairly rich -- it's not all mood and atmosphere, and the horror imagery becomes increasingly more explicit, before drawing back again into insinuation by the end. Along the way, Crisp writes of the strangeness of humanity, the seeming near-emptiness of Ynys-y-Plag, a town rich with creeping, eerie nature that itself is dotted with man-made structures, such as bridges, the dome, the lights that light the trees as night falls -- it's like weeds growing through a split in the pavement, but in reverse. Yet there's almost no one around. The photographer meets three townspeople within Ynys-y-Plag limits. The photographer learns about that swing, and about the bug the man -- "The Otter Man," the photographer dubs him -- warned about, or rather, in Welsh, the bwg, which itself, we are told, is the origin of "bug," but when we see centipedes and millipedes and flies and caterpillars and think "bug," that is a misuse of an ancient word with an ancient meaning that we can't know about, though we are probably in some subtle, unnoticed way infected by the "bwg," the disease that crouches within Ynys-y-Plag. If there's a horror image Crisp wants you to leave his story and dig up for yourself, and presumably connect to "Ynys-y-Plag," it's this little...lady? The Kikimora, anyway, a monster from Slavic myth, illustrated here -- and this is the exact picture Crisp specifically refers to on three different occasions -- by Ivan Bilibin:

I hasten to add, this isn't cheating on Crisp's part. It's a symbol.

Thomas Ligotti once said that the next great horror writer would be someone writing from the fringe of society, a badly socialized and slightly, but genuinely, unhinged person like, he said, H. P. Lovecraft or Edgar Allan Poe ("or me," he didn't say, but didn't need to, but he would have been right if he had). I don't know enough about Crisp to say if he fits the model, but from what I've read of his work, some of the recurring ideas are a resistance to suicide only because "Why bother?" is just as strong in its lack of action as suicide would be in its action, a crippling loneliness that one doesn't fight to conquer but to accept, a fear of sex, a disgust of sex, an inability to take pleasure from sex, abuse and cruelty and terror and confusion. "Ynys-y-Plag" itself uses occasionally blatant horror ideas to deal with almost all of this, as well as the loss of childhood and family and home -- the growing into adulthood as the awakening into horror. The more straightforward horror elements of the novella are among the more unsettling I've encountered in some time (a dead body is described without detail but with just the right simile that I could picture it instantly, and was jarred by what Crisp was showing me), and the ideas, very much like Ligotti though not quite antinatal, are at least regretful about that the idea of "human life" was ever considered.

"Ynys-y-Plag" is not perfect. Towards the end, Crisp goes about explaining more than I would have expected. There's a lot he doesn't explain, but explaining almost any of what's going on here is surprising in a story like this. It becomes very talky as a result, but by no means fatally so. Not even close. Whatever flaws pop up along the way, the final, overall effect of "Ynys-y-Plag" is one of hopeless, queasy terror -- the terror of uncertainty and of loss, and of not being a part of a world that everyone else seems to be a part of, of life, of death, and of a universe that possibly not only doesn't care about you, but hates you. In the hands of an honest writer, this is horror.

Showing posts with label Thomas Ligotti. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Thomas Ligotti. Show all posts

Tuesday, October 16, 2012

Saturday, June 16, 2012

You’re Tired of Yourself and All of Your Creations

[Some spoilers for Prometheus follow]

In his study The Nature of Evil (1931) Radoslav A. Tsanoff cites a terse reflection set down by the German philosopher Julius Bahnsen in 1847, when he was seventeen years old. "Man is a self-conscious Nothing," wrote Bahnsen. Whether one considers these words to be juvenile or precocious, they belong to an ancient tradition of scorn for our species and its aspirations. All the same, the reigning sentiments on the human venture normally fall between qualified approval and loud-mouthed braggadocio. As a rule, anyone desirous of an audience, or even a place in society, might profit from the following motto: "If you can't say something positive about humanity, then say something equivocal."

...In Bahnsen's philosophy, everything is engaged in a disordered fantasia of carnage. Everything tears away at everything else...forever. Yet all this commotion in nothingness goes unnoticed by nearly everything involved in it. In the world of nature, as an instance, nothing knows of its embroilment in a festival of massacres. Only Bahnsen's self-conscious Nothing can know what is going on and be shaken by the tremors of chaos at feast.

- Thomas Ligotti, The Conspiracy Against the Human Race

"You think we wasted our time coming here, don’t you?"

"Your question depends on me understanding what you hoped to achieve by coming here."

"What we hoped to achieve was to meet our makers. To get answers. Why they even made us in the first place."

"Why do you think your people made me?"

"We made you because we could."

"Can you imagine how disappointing it would be for you to hear the same thing from your creator?"

- dialogue between Charlie Holloway and David, a robot, from Prometheus

Yellow matter custard

Dripping from a dead dog's eye

Crabalocker fishwife

Pornographic priestess

Boy, you've been a naughty girl

You let your knickers down

I am the eggman

They are the eggmen

- The Beatles, "I Am the Walrus"

I have not read a word of any of the reviews for Ridley Scott's Prometheus. All I know about the reactions from both critics and the public is, roughly, that while some people have been impressed to varying degrees, from praising it enthusiastically as a smart and visually stunning piece of science fiction, to appreciating it as a good time at the movies, most seem to look at it as a crushing disappointment, one that is even, to hear some tell it, catastrophically stupid. These negative reactions seem to have stemmed, at least in part, from a belief going into the theater that Prometheus was intended to be a prequel to Scott's 1979 masterpiece Alien, with all the links and nods and associated gewgaws that go along with that idea. Scott himself has denied this, or rather has hedged his bets by saying that Prometheus was not strictly that and shouldn't be approached as such. And guess what, he's right, it isn't and shouldn't be. It's true that Scott announces that this film very clearly exists in the universe of Alien and its sequels, in ways both subtle and extremely blatant, but for myself, I couldn't care less about that. Not that I disliked the moments that connected to earlier movies -- specifically Alien; the later movies don't even seem to be a consideration here -- but rather that I think Prometheus is entirely a stand-alone film, paired up with the 1979 original only in the same way that The Honeymoon Killers and Barton Fink pair up by virtue of both taking place in the 1940s.

No, what Prometheus is playing is an entirely different game. Within the same genre, obviously -- like Alien, Prometheus is a science fiction film until it's a horror film. The script by John Spaihts and Damon Lindelof plays things very mysterious, from the beginning, which depicts a strange white alien consuming water from a river and seeming to disintegrate, or to begin to, to an ending that acknowledges everything we don't know about what has transpired. In between, it tells the story of a group of scientists, led by Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace) and Charlie Holloway (Logan Marshall-Green), who are sailing through space in a ship called Prometheus and owned by the Weyland Corporation, to a destination and for a purpose few of them know, until they're awakened from their two-year cryogenic sleep by David (Michael Fassbender), a robot who appears to have spent much of his lonely down time obsessing over Peter O'Toole in Lawrence of Arabia, a film he has watched over and over again. Once awakened, we get a sense of some of the other scientists and crewmembers, such as Janek (Idris Elba), the Prometheus's captain, and Meredith Vickers (Charlize Theron), a Weyland representative and the mission's true boss who doesn't seem to have to work very hard to tamp down on any sort of natural empathy that might otherwise get in the way of her making the hard decisions. That mission, we soon learn from Elizabeth and Holloway, as well as a hologram of the ancient and, the hologram assures us, dead by the time of this viewing, Peter Weyland (Guy Pearce), is to locate a planet in a galaxy far beyond our own that has been mapped out using clues that Elizabeth and Holloway have discovered in ancient Earth cave drawings, clues that have led the two scientists to believe -- and Weyland, too, when he was alive -- that Earth was visited by aliens long, long ago. Evidence even suggests that these aliens were our own creators, that is, they somehow created all of humanity. Though he knew he wouldn't be alive to witness this, Weyland's hologram says, it is his desire to facilitate the meeting of our makers.

For a while, the plot proceeds along about how you'd imagine: the Prometheus finds and lands on the planet; a scientific expedition sets out and finds that aliens were here and were of a very extraordinary intelligence, to the degree that within the bizarre buildings they constructed they also managed to create a breathable atmosphere; and soon things become weird and unsettling, as no actual living aliens are found, but the corpse of one is discovered, apparently decapitated by a door, and the head, with some difficulty, is bundled up and brought back to the ship.

And then a lot of other stuff happens. At a certain point, Prometheus quite frankly goes bugfuck. It has also set up a lot of ideas that are pretty damn big, so big that for a while I was unsettled about how it was all going to be handled. For starters, Elizabeth is a Christian, of the sort who is always searching, optimistically, even a little moonily, for answers. And the film's title, and the ship's name, comes from the Greek myth of, logically enough, Prometheus, who, among other things, was said to have created humanity from clay. Then, too, you have David, the robot, whose own existence is a modern and potentially possible literalization of the Prometheus myth. Then later, in a moment that earns that whole "on the nose" epithet they got now, a conversation between Elizabeth and Holloway, who are lovers, about the now-apparent ease and unexceptional nature of creating life, reveals that Elizabeth is unable to have children, in other words, unable to create life herself. But where this all goes is entirely shocking. Elizabeth's mooniness is hers alone.

Along with the eventual bugfuckery, Scott begins to let influences become absorbed into the narrative. The film opens with a shot straight from 2001: A Space Odyssey, and after a while David goes all HAL on everything, becoming quietly and alarmingly sinister, his motivations occasionally unclear, but you get the sense that whatever else he's been programmed to do, he has himself begun to wonder about his own place in the chain of life and to aggressively manipulate those parts of humanity available to him so that he can make clear to himself, and to his creators, that everything is nothing, and that existence may be desirable, but is also the sprawling endless desert he knows from his favorite film. Another of Scott's big influences seems to have been his own Blade Runner, and why not? David's malevolence may be quieter than that of Roy Batty, but it is no less destructive, or, finally, no less easy to understand. I'm also reminded of a line change from Blade Runner, where originally a bit of dialogue was written to include the word "father" but was replaced in the film with "fucker," for various reasons, and how the word "father" is used in Prometheus in a possibly similar context as it was meant for in Blade Runner, or then again maybe not, and how in any case the ambiguity that word completely fails to clear up in regards to a particular character's identity rather nicely matched other science fiction themes Scott enjoys exploring. Except in his final cut of Blade Runner, where he wants more or less plain answers to a question that I, personally, never wanted asked in the first place. Which means I like the theatrical cut of Blade Runner the best. Is all of this neither here nor there? Despite appearances, it might not be.

Anyway, not only is existence nothing, but creation itself is at best an indifferent act, and at worst a malicious one. Throughout the film, creating something results in that creation being unwanted, or hated, or hating its creator. Most commonly the creator, which may sometimes be a symbolic role, loathes and wishes to destroy what it has made. Why? Sometimes that's clear, sometimes it's less a question than a philosophical howl that could be simplified by another unanswerable, even rhetorical, question, for those who possess a certain life philosophy, of why, if God exists, there is so much room for horror in life. But you have a woman devastated by her inability to conceive going to extreme lengths to rid herself of the one ghastly version of conception the universe has seen fit to bestow on her (in a scene that, by the way, is one of the craziest bits of horror movie chaos I've witnessed in an ostensibly mainstream film in a very long time), and you have a direct question asked by the hopeful and wonder-filled to what can only be thought of as their God responded to with a frenzy of wordless murder. In Prometheus, asking the basic questions about life will lead only to death and terror. Going about your life with your head down might be the more rational way to go.

In this way, and others, Prometheus is not unlike the Coen brothers' A Serious Man, in which Michael Stuhlbarg's Larry Gopnik gropes for answers as his life shatters into ever-smaller pieces, until by the end he is perhaps facing death, his community and family possibly the same, his questions greeted with gibberish or silence. But not, perhaps, hopeless silence. Prometheus presents another questing believer, though Elizabeth will not budge in the face of the sprays of blood and wild destruction by the creator of the created. She still wants to know why. Near the end of the film, she expresses a desire to know why certain minds have been changed, and it's a line, in retrospect, I wish to a degree had never been asked, though in fairness that line's very existence allowed me to realize that I hadn't missed a crucial point -- the shocking thing at the heart of her new quest simply happened, and was as unknowable as it appeared.

Despite everything, a continued need to believe and ask questions might signal an optimism in Prometheus that doesn't exist, at least not in any kind of clearly understandable way, in A Serious Man, but Scott continues on with one more scene that many people would probably brush off as Scott's most explicit link to Alien, and possibly even a winking acknowledgment that should all go well financially we could all be in store for a sequel, but what it really is, in tone and philosophy, is one more example of creation horror. Life brings death, says biology, but life brings violence and murder, says Prometheus. Prometheus, which I consider (perhaps in a knee-jerk way since I just saw it this morning) one of the finest horror movies of the past decade -- and it ends up as that more than it begins as a work of science fiction -- follows what horror writer Thomas Ligotti has often argued, and which you don't have to believe yourself to feel the fist in your gut, which is that existence and creation are terrible mistakes, and to blunder along engaged in either one will only lead to suffering.

Monday, October 25, 2010

The Kind of Face You SLASH!!! - Day 25: Who Knows the Stench of God?

Dark Awakenings by Matt Cardin is an unusual book. Not that I've read it all, but you can tell by the way its contents break down that it's not a typical horror collection. First off, you have your horror fiction, separated into a section called, appropriately enough, "Fictions". There are seven of these, including a novella called "The God of Foulness" (which I'm afraid I did not read for today, something I, having read the first few paragraphs, now rather regret), and they take up about 180 of the book's 300 pages. The remainder of the book is taken up with a series of academic essays by Cardin about the horror genre, and religion, and where the two converge in art and -- so I've gathered is the idea anyway -- in real life. Meanwhile, the dust jacket copy reads, in part:

.

[A]uthor and scholar Matt Cardin explores this ancient intersection between religion and horror in seven stories and three academic papers that pose a series of disturbing questions: What if the spiritual awakening coveted by so many religious seekers is in fact the ultimate doom? What if the object of religious longing might prove to be the very heart of horror? Could salvation, liberation, enlightenment then be achieved only by identifying with that apotheosis of metaphysical loathing?

.

Could be. All sorts of things are possible. But who can know? So that's Cardin's angle anyway, and I'm honestly quite intrigued. As it pertains to a real world philosophy, I believe Cardin is a bit, I don't know...fucked in the head, I think is the term, and more than likely doesn't even mean it, but as a literary philosophy to be applied to the writing of horror fiction, then okay, pal, let's have it. Plus, it's not hard to see from the above why Cardin -- whose second book this is, his first being the 84-page Divinations of the Deep, the contents of which I haven't been able to ascertain -- is often mentioned in the same breath as Thomas Ligotti (and also Reggie Oliver, although in that case the connection isn't as obvious. Anyway, I heard about Cardin in relation to Oliver, when horror critic Jim Rockhill said that Cardin and Ligotti were the only modern horror writers capable of writing at Oliver's level).

.

For the record, the reason I now regret not reading "The God of Foulness" is because of the two Cardin stories I did read for today, one plays as a sort of declaration of intent, or as Cardin's personal horror manifesto, while the other seems to bear no clear relation to that manifesto, and is merely an excellent piece of horror writing (it's better than the manifesto, actually). "The God of Foulness", on the other hand, from my brief scan of its opening pages, is evidently about a religious cult who seeks out disease as a means of spiritual completion. So there you go, that probably would have been good to read, but no, I had to fuck it all up. But enough: let's get to what I actually did read, and see what shakes out.

.

I'll begin with the manifesto, which is called "The Devil and One Lump". This is the story of a man named Evan, who was once "king of the mid-list horror writers", specializing in a brand of religious horror that sounds very much like the dust jacket flap of Dark Awakenings. As a character in the story describes it:

.

You have created protagonists whose very search for salvation produces a backfire effect that damns them to a worse hell than they had ever imagined. You have speculated that the Bible contains a hidden subtext that runs between the actual printed lines and undermines the surface message at every turn. You have written of a narcissistic demiurge who is so enraptured by the beauty of his own creation that he represses the memory of his birth from a monstrous prior reality, so that when he is forcibly reawakened to this memory, he suffers a psychological breakdown that generates cataclysmic consequences both for himself and for the cosmos he created.

.

This description of Evan's work is delivered by the Devil, and "The Devil and One Lump" is the sort of sardonic, one-room-setting, horror story version of movies like Bedazzled, where the Devil forces his point of view onto the misbegotten hero, and tests that hero's feeble philosophy, meanwhile revealing the Great Chess Match between Satan and God that uses folks like Evan as their pawn, and et cetera. Which means that "The Devil and One Lump" is sort of a comedy, and this is too bad. Though I hate this word, and am not in agreement with the philosophy, there is something truly subversive about "The Devil and One Lump" and the way it plays out, particularly the ending -- the material is here for a truly disquieting horror story. Unfortunately, the story takes place on two different planes of reality, and the connective tissue between the two is Evan's quest for his morning cup of coffee. This might put you in mind of the kind of mundanity mixed with cosmic absurdity for which Douglas Adams was so renowned, but "The Devil and One Lump" is minus all those pesky laughs Adams kept cramming in there.

.

It's possible I'm being too harsh here -- "The Devil and One Lump" isn't written to be a romp -- but it's hard for me to take Cardin's approach to horror seriously when this is my first exposure to him. Possibly this is my fault, as I made the choice of where to begin, but all I'm getting here is an announcement hidden in a story, and one that's not particularly illustrative of Cardin's ideas. It's fairly explicit about those ideas, but that's not quite the same thing.

.

One the other hand, we have "Blackbrain Dwarf", a story chosen by me because I thought that title was quite the grabber. As I mentioned before, this story is not especially in line, or not obviously in line, with Cardin's religion-horror philosophy, but that's only a problem for me, as far as writing this post goes, not for Cardin. Where's it written that you have to write the same kind of story all the time, even if you always wrote within one genre? And why exactly would you want to? If you're Robert Aickman, you can pull it off, but, as a matter of fact, if Thomas Ligotti has one serious problem as a writer -- and I'm an enormous admirer of his work -- it's that he's in danger becoming a bit of a self-parody. It's all strange towns with faceless citizens and psychotic businesses and mad art, and so on -- when he breaks out of it with a story like "Alice's Last Advenutre" or the deeply interesting and unnerving "Notes on the Writing of Horror: A Story", it's jarring because I'm simply not used to it. So get it together, Thomas Ligotti. What the fuck. And good job Matt Cardin for mixing up your shit a little. Probably, I guess -- I've only read the two so far.

.

So "Blackbrain Dwarf". This story is about Derek Warner, and the last day in which he experiences any moments of sanity. And there aren't many of those. Here's how it begins:

.

But of course everything was all wrong. Derek knew it the minute he opened his eyes and perceived the vileness resounding from every angle and object in the room. Indeed, how could it be otherwise in a red-glowing world where the stench of blacksouls mounts to a deadening sky?

.

When Derek's mind slips from our reality, it's signalled by those italics, and sudden Dark Ages/Lovecraftian bursts of thundering, blood-and-doom-soaked language. I have to say that "Blackbrain Dwarf" -- which is nothing to speak of as a plot, nor does it suffer for that -- is actually a pretty bracingly chilling story. The dwarf of the title is an evil little man who whispers the terrifying words into Derek's ear that lead to his total absorption into that fearsome world that keeps breaking into his daily reality as an unhappy lawyer in an unhappy marriage. The language of that other world has an awful poetry to it, and the idea that it didn't come from within Derek's mind, but was indeed from elsewhere, and was burrowing into Derek's mind made "Blackbrain Dwarf" all the more effective, as was the detail of a victim of Derek's late-story violent impulses repeatedly crying out "What's wrong!?", because their fear-blasted mind could find nothing else to say.

.

So I was very impressed with "Blackbrain Dwarf", much less so with "The Devil and One Lump", but my only regret about this attempt to discuss the work of Matt Cardin is that there's a great deal of depth being implied in descriptions of what Dark Awakenings is, and what Matt Cardin is all about, and it may well all be true, but my choice of stories for today didn't really give me an opportunity to explore any of that. I read a couple of horror stories, as usual. But I don't think there's much that's usual about Cardin, for better or worse, so I'll keep reading.

.

[A]uthor and scholar Matt Cardin explores this ancient intersection between religion and horror in seven stories and three academic papers that pose a series of disturbing questions: What if the spiritual awakening coveted by so many religious seekers is in fact the ultimate doom? What if the object of religious longing might prove to be the very heart of horror? Could salvation, liberation, enlightenment then be achieved only by identifying with that apotheosis of metaphysical loathing?

.

Could be. All sorts of things are possible. But who can know? So that's Cardin's angle anyway, and I'm honestly quite intrigued. As it pertains to a real world philosophy, I believe Cardin is a bit, I don't know...fucked in the head, I think is the term, and more than likely doesn't even mean it, but as a literary philosophy to be applied to the writing of horror fiction, then okay, pal, let's have it. Plus, it's not hard to see from the above why Cardin -- whose second book this is, his first being the 84-page Divinations of the Deep, the contents of which I haven't been able to ascertain -- is often mentioned in the same breath as Thomas Ligotti (and also Reggie Oliver, although in that case the connection isn't as obvious. Anyway, I heard about Cardin in relation to Oliver, when horror critic Jim Rockhill said that Cardin and Ligotti were the only modern horror writers capable of writing at Oliver's level).

.

For the record, the reason I now regret not reading "The God of Foulness" is because of the two Cardin stories I did read for today, one plays as a sort of declaration of intent, or as Cardin's personal horror manifesto, while the other seems to bear no clear relation to that manifesto, and is merely an excellent piece of horror writing (it's better than the manifesto, actually). "The God of Foulness", on the other hand, from my brief scan of its opening pages, is evidently about a religious cult who seeks out disease as a means of spiritual completion. So there you go, that probably would have been good to read, but no, I had to fuck it all up. But enough: let's get to what I actually did read, and see what shakes out.

.

I'll begin with the manifesto, which is called "The Devil and One Lump". This is the story of a man named Evan, who was once "king of the mid-list horror writers", specializing in a brand of religious horror that sounds very much like the dust jacket flap of Dark Awakenings. As a character in the story describes it:

.

You have created protagonists whose very search for salvation produces a backfire effect that damns them to a worse hell than they had ever imagined. You have speculated that the Bible contains a hidden subtext that runs between the actual printed lines and undermines the surface message at every turn. You have written of a narcissistic demiurge who is so enraptured by the beauty of his own creation that he represses the memory of his birth from a monstrous prior reality, so that when he is forcibly reawakened to this memory, he suffers a psychological breakdown that generates cataclysmic consequences both for himself and for the cosmos he created.

.

This description of Evan's work is delivered by the Devil, and "The Devil and One Lump" is the sort of sardonic, one-room-setting, horror story version of movies like Bedazzled, where the Devil forces his point of view onto the misbegotten hero, and tests that hero's feeble philosophy, meanwhile revealing the Great Chess Match between Satan and God that uses folks like Evan as their pawn, and et cetera. Which means that "The Devil and One Lump" is sort of a comedy, and this is too bad. Though I hate this word, and am not in agreement with the philosophy, there is something truly subversive about "The Devil and One Lump" and the way it plays out, particularly the ending -- the material is here for a truly disquieting horror story. Unfortunately, the story takes place on two different planes of reality, and the connective tissue between the two is Evan's quest for his morning cup of coffee. This might put you in mind of the kind of mundanity mixed with cosmic absurdity for which Douglas Adams was so renowned, but "The Devil and One Lump" is minus all those pesky laughs Adams kept cramming in there.

.

It's possible I'm being too harsh here -- "The Devil and One Lump" isn't written to be a romp -- but it's hard for me to take Cardin's approach to horror seriously when this is my first exposure to him. Possibly this is my fault, as I made the choice of where to begin, but all I'm getting here is an announcement hidden in a story, and one that's not particularly illustrative of Cardin's ideas. It's fairly explicit about those ideas, but that's not quite the same thing.

.

One the other hand, we have "Blackbrain Dwarf", a story chosen by me because I thought that title was quite the grabber. As I mentioned before, this story is not especially in line, or not obviously in line, with Cardin's religion-horror philosophy, but that's only a problem for me, as far as writing this post goes, not for Cardin. Where's it written that you have to write the same kind of story all the time, even if you always wrote within one genre? And why exactly would you want to? If you're Robert Aickman, you can pull it off, but, as a matter of fact, if Thomas Ligotti has one serious problem as a writer -- and I'm an enormous admirer of his work -- it's that he's in danger becoming a bit of a self-parody. It's all strange towns with faceless citizens and psychotic businesses and mad art, and so on -- when he breaks out of it with a story like "Alice's Last Advenutre" or the deeply interesting and unnerving "Notes on the Writing of Horror: A Story", it's jarring because I'm simply not used to it. So get it together, Thomas Ligotti. What the fuck. And good job Matt Cardin for mixing up your shit a little. Probably, I guess -- I've only read the two so far.

.

So "Blackbrain Dwarf". This story is about Derek Warner, and the last day in which he experiences any moments of sanity. And there aren't many of those. Here's how it begins:

.

But of course everything was all wrong. Derek knew it the minute he opened his eyes and perceived the vileness resounding from every angle and object in the room. Indeed, how could it be otherwise in a red-glowing world where the stench of blacksouls mounts to a deadening sky?

.

When Derek's mind slips from our reality, it's signalled by those italics, and sudden Dark Ages/Lovecraftian bursts of thundering, blood-and-doom-soaked language. I have to say that "Blackbrain Dwarf" -- which is nothing to speak of as a plot, nor does it suffer for that -- is actually a pretty bracingly chilling story. The dwarf of the title is an evil little man who whispers the terrifying words into Derek's ear that lead to his total absorption into that fearsome world that keeps breaking into his daily reality as an unhappy lawyer in an unhappy marriage. The language of that other world has an awful poetry to it, and the idea that it didn't come from within Derek's mind, but was indeed from elsewhere, and was burrowing into Derek's mind made "Blackbrain Dwarf" all the more effective, as was the detail of a victim of Derek's late-story violent impulses repeatedly crying out "What's wrong!?", because their fear-blasted mind could find nothing else to say.

.

So I was very impressed with "Blackbrain Dwarf", much less so with "The Devil and One Lump", but my only regret about this attempt to discuss the work of Matt Cardin is that there's a great deal of depth being implied in descriptions of what Dark Awakenings is, and what Matt Cardin is all about, and it may well all be true, but my choice of stories for today didn't really give me an opportunity to explore any of that. I read a couple of horror stories, as usual. But I don't think there's much that's usual about Cardin, for better or worse, so I'll keep reading.

Friday, October 2, 2009

The Kind of Face You SLASH!!! - Day 2: How I Detest Those Fools

In the category of the modern weird story, it’s hard to know quite where to place Mark Samuels. This is probably because, outside of Thomas Ligotti and a few others, very few contemporary horror writers do anything more than dabble in this vaguely defined subgenre – it can’t help that, in my case, I only read my first pair of Samuels stories a few days ago, a fact which is, itself, explained by the troubling rarity of his books. His first collection, The White Hands and Other Weird Tales was first published in 2003 by Tartarus Press, and is currently out of print. His most recent book, Glyphotech, was published by PS Publishing in 2008, and it, too, is out of print. Used copies of each, as well as the two Samuels books that were published in between, fetch a very steep price, unless you happen to luck out (as I did, in the case of White Hands, at least). What this says about the state of the modern horror fiction market – both Tartarus and PS Publishing are very small presses – is both very clear and entirely depressing, so it’s best that we move on.

In the category of the modern weird story, it’s hard to know quite where to place Mark Samuels. This is probably because, outside of Thomas Ligotti and a few others, very few contemporary horror writers do anything more than dabble in this vaguely defined subgenre – it can’t help that, in my case, I only read my first pair of Samuels stories a few days ago, a fact which is, itself, explained by the troubling rarity of his books. His first collection, The White Hands and Other Weird Tales was first published in 2003 by Tartarus Press, and is currently out of print. His most recent book, Glyphotech, was published by PS Publishing in 2008, and it, too, is out of print. Used copies of each, as well as the two Samuels books that were published in between, fetch a very steep price, unless you happen to luck out (as I did, in the case of White Hands, at least). What this says about the state of the modern horror fiction market – both Tartarus and PS Publishing are very small presses – is both very clear and entirely depressing, so it’s best that we move on.I first heard about Mark Samuels a few years ago when, in the early throes of my newfound passion for the fiction of Thomas Ligotti, I read an interview with the latter writer, in which the two were roughly compared. Essentially, Ligotti acknowledged Samuels as someone he was in tune with, but wondered if writers like Samuels were disturbed, and cut off from regular society, enough to achieve the stature in the horror field enjoyed by the likes of Poe, Lovecraft and (he doesn’t say but implies) himself.

Probably not, is the answer. Samuels, as it happens, is that rarest of creatures: a 21st century writer of horror fiction who is also a Christian – a Catholic, to be exact. On his website, Samuels writes:

Frankly, one has to tread carefully on horror messageboards if one admits to having faith. Particularly if you’re a Catholic (which I am, albeit not much of a churchgoing one). Once this fact is discovered it seems to be the case that it’s open season on your beliefs. I guarantee you’ll be the target of all sorts of wily attempts to draw you into an argument designed to make you see the errors of your ways and embrace the “rationality” of atheism (or agnosticism, most of whose adherents are, it seems, practically 99% atheist, but hold back a 1% doubt in order not to appear too judgemental).

And elsewhere on the site:

God, for me, is the fundamental core of reality itself. God does not exist, in the way we know a certain mountain exists. Without God there is no reality; God is the prime consciousness. God is infinite and eternal. He (I use the term “he” only for convenience) is not able to be directly understood by man, although we have intimations that allow us to conceive of his nature.

Science is not incompatible with belief in God. Since God is eternal and infinite, a process such as evolution, which may seem an incredibly inefficient way of producing humankind, is only inefficient from our temporal perspective.

Science cannot tell us why there are laws of physics. If one responds that this question is an irrelevance, since science makes no claim to explain the why in this instance, then it is an example that science cannot explain science. No closed system can explain a closed system.

If you don’t spend a great deal of time reading contemporary horror fiction -- and so it would follow you wouldn’t be spending any time on horror messageboards – you’ll have to take my word for it that Samuels is absolutely correct about the ways in which faith is treated in that community. Ligotti, the writer to whom Samuels is most often linked, is a full-bore atheist, at one point accepting the purely metaphorical existence of a creator only so that he could blame someone or something for the nightmare of human existence.

So all of this places Samuels in a unique position. In his faith, and fictional subject, he really does hearken back to the old days of Machen and M. R. James, a comparison that isn’t coincidental once you actually start reading Samuels’s fiction. His Catholicism isn’t exactly explicit in his story “White Hands” – a story I’ll get to in a bit -- though once you know his faith, the reader can sort of say, “Oh, okay. Sure.” Which is completely fine, and serves the story, or doesn’t, depending on what you want. Unfortunately, Samuels attempt to place his faith front and center doesn’t pay off too well in the other story I read, called “The Grandmaster’s Final Game”. Though the truth is that the Catholic nature of the story isn’t the problem – not only is that hardly the kind of thing that I, personally, am likely to complain about, but where would The Exorcist be without its faith? – but rather Samuels’s inability make the elements of this story cohere. Essentially a story of demonic possession and chess, most of “The Grandmaster’s Final Game” is told in the form of a confession told to Father Mooney by a man named Leonard Hughes. Hughes has specifically sought out Father Mooney to deliver his confession because, he says, “I know you were one of the finest chess players in Europe before you were called to holy orders.” Hughes goes on to tell of his life as a professional chess player, a career which didn’t take off until he found a bizarre chess set being sold for next to nothing in a local bookshop. The set was made unique by, among other things, featuring only black chess pieces. As I’ve already revealed that this is a story of possession, you can probably guess where we’re heading, and you’ll be correct.

Which is obviously a problem, but is not the problem, and, in fact, didn’t need to even be a problem at all. Though I strongly resist the idea that genre fiction – and, really, pick your genre, because this is said about them all – must necessarily follow formula and pay off in the way the reader expects, and that the only thing that can distinguish one genre writer from another is style and technique, I also know full well that great, brilliant work can be done while adhering to a given formula. So Samuels, a good writer who is a Catholic, and who, additionally, is very knowledgeable about his chosen genre, should have sailed through “The Grandmaster’s Final Game”. But he doesn’t. For one thing, there is no genuine sense of the infernal, something you obviously can’t say about The Exorcist, so that the inevitable final chess match feels as though it’s being waged between a priest who really wants to win, and a guy who really hates to lose.

Which is obviously a problem, but is not the problem, and, in fact, didn’t need to even be a problem at all. Though I strongly resist the idea that genre fiction – and, really, pick your genre, because this is said about them all – must necessarily follow formula and pay off in the way the reader expects, and that the only thing that can distinguish one genre writer from another is style and technique, I also know full well that great, brilliant work can be done while adhering to a given formula. So Samuels, a good writer who is a Catholic, and who, additionally, is very knowledgeable about his chosen genre, should have sailed through “The Grandmaster’s Final Game”. But he doesn’t. For one thing, there is no genuine sense of the infernal, something you obviously can’t say about The Exorcist, so that the inevitable final chess match feels as though it’s being waged between a priest who really wants to win, and a guy who really hates to lose.

On a much more encouraging note, the other Samuels story I read was “White Hands”, and it follows a familiar track of weird fiction in that it concerns itself with horror fiction and scholarship. The story is about an ambitious unnamed narrator who seeks out Alfred Muswell, at once a well-known academic and scholar of of “literary ghost stories”. Muswell was a disgraced former don at Oxford, who instructed his students to focus their reading on the works of J. Sheridan Le Fanu, Vernon Lee, M. R. James and Lilith Blake (Blake being the one fictional character on this list, and, the reader discovers, the source of the story's horror). Though Muswell is a scholar of all of these writers, when Muswell meets our narrator and discovers that he prefers the work of Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood, Muswell immediately dismisses those other writers (of Machen he says, "That red-face old coot with his deluded Anglo-Catholic rubbish!") and says:

On a much more encouraging note, the other Samuels story I read was “White Hands”, and it follows a familiar track of weird fiction in that it concerns itself with horror fiction and scholarship. The story is about an ambitious unnamed narrator who seeks out Alfred Muswell, at once a well-known academic and scholar of of “literary ghost stories”. Muswell was a disgraced former don at Oxford, who instructed his students to focus their reading on the works of J. Sheridan Le Fanu, Vernon Lee, M. R. James and Lilith Blake (Blake being the one fictional character on this list, and, the reader discovers, the source of the story's horror). Though Muswell is a scholar of all of these writers, when Muswell meets our narrator and discovers that he prefers the work of Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood, Muswell immediately dismisses those other writers (of Machen he says, "That red-face old coot with his deluded Anglo-Catholic rubbish!") and says:“…No, no. Believe me, if you want the truth beyond the frontier of appearances it is to Lilith Blak you must turn. She never compromises. Her stories are infinitely more than mere accounts of supernatural phenomena…”

As the reader will shortly learn. Despite his ambivalence about her, our narrator is looking to make his name by writing a monograph on Lilith Blake, a proposition that becomes more and more likely the more time he spends with Muswell. He sought out Muswell in the first place because Muswell is the foremost – and probably only – expert on Blake’s life and writing, and once our narrator has gained his confidence, the older scholar makes his collection of pictures, biographical material and unpublished writing free to the young man. Everything except one unpublished book called The White Hands and Other Tales. Muswell explains:

”This volume…contains the final stories. They establish the truth of all that I have told you. The book must now be published. I want to be vindicated after I die. This book will prove, in the most shocking way, the supremacy of the horror tale over all other forms of literature. As I intimated to you once before, these stories are not accounts of supernatural phenomena but supernatural phenomena in themselves.”

Samuels’s terrific story – both old-fashioned and unique – is one of those small but intriguing number of works of horror fiction that seems to take the horror genre itself as its subject (others in this category that I can think of off the top of my head are Joe Hill’s chilling “Best New Horror”, Ligotti’s bizarre “Notes on the Writing of Horror: A Story”, and the Amicus film The Skull). Lilith Blake is clearly bad news, and at least two men, two fans, get sucked far too deeply into the genre’s genuinely black heart. Muswell, in fact, disdains all other kinds of fiction, and the title of this post, How I Detest Those Fools, is taken from a line delivered by Muswell about a group of scholars studying James Joyce. Horror is all to him, and it will become all for our narrator. The nastiness and violence and hopelessness of horror consumes them. Had they enjoyed some other kind of reading material, there would be no “White Hands” by Mark Samuels. Though I suppose there still would be a “White Hands” by Lilith Blake, waiting for some other poor curious soul to take things too far.

Samuels’s terrific story – both old-fashioned and unique – is one of those small but intriguing number of works of horror fiction that seems to take the horror genre itself as its subject (others in this category that I can think of off the top of my head are Joe Hill’s chilling “Best New Horror”, Ligotti’s bizarre “Notes on the Writing of Horror: A Story”, and the Amicus film The Skull). Lilith Blake is clearly bad news, and at least two men, two fans, get sucked far too deeply into the genre’s genuinely black heart. Muswell, in fact, disdains all other kinds of fiction, and the title of this post, How I Detest Those Fools, is taken from a line delivered by Muswell about a group of scholars studying James Joyce. Horror is all to him, and it will become all for our narrator. The nastiness and violence and hopelessness of horror consumes them. Had they enjoyed some other kind of reading material, there would be no “White Hands” by Mark Samuels. Though I suppose there still would be a “White Hands” by Lilith Blake, waiting for some other poor curious soul to take things too far.

-------------------------------------------

UPDATE 10/12/09: In the comments section, a fellah by the name of "tartarusrussell" informs me that not only is Mark Samuels's The White Hands and Other Weird Tales not out of print, but is available for a very reasonable price through Tartarus Press here. Call me a shill if you must, but Samuels deserves to have somebody shilling for him. Even if it's only me.

Wednesday, March 11, 2009

Tar or Milk?

Raindrops fell like tears from a black tar god -- or drops of rancid milk from a dead mother's breast.

Raindrops fell like tears from a black tar god -- or drops of rancid milk from a dead mother's breast.That line comes from The Rising, the first novel by horror writer Brian Keene, and when I read it, mere minutes ago, I had to ask myself (since Keene wasn't available to ask personally): "Well, which is it? Tears from a black tar god and rancid breast milk sound like two pretty different things to me. Presumably, one is black and the other is white, or off-white. So is the rain black or white, or just normal rain-colored? And if that's irrelevant to you, then how can rain fall 'like breast milk'? I can allow that tears from a black tar god might fall like rain, because gods are not only big, but tend to be located above-ground, so I'm fine with that. But when has breast milk ever rained down on anything?"

It appears to me as though Keene simply wasn't satisfied with black tar god tears standing in for rain, and needed another image that involved liquid -- preferably gross liquid, as that seems to be his MO -- to pair it up with, so that readers could take their pick. But it's terrible writing. It's a meaningless cluster of similes that also indicates that you've placed yourself in the hands of a writer who is, among other things, indecisive.

Just a few pages later:

She was safe for now.

Or was she? What if there was a zombie in here with her, lurking in the darkness, waiting to lunge out and eat her?

I don't know, Brian Keene, you tell me. You're the guy who wrote the book. But thanks for reminding me that this is a zombie novel I'm reading. I'd very nearly forgotten! And I do also appreciate this window into the mind of the character. Knowing that she's worried about being eaten by a zombie really brings her alive.

Just a few paragraphs down:

...she couldn't see her ears, but she knew they were scarlet.

Hey, I can't see my ears, either, unless there's a mirror handy! It's like I know this girl!

You get the idea. This book is just grade-school bullshit. I'm writing this out of an immense feeling of frustration, which coincides with a bit of introspection regarding why I seem to want to continue to cling to the horror genre. The vast majority of it does me very few favors. And I certainly can't find my way to thinking of myself as a member of the horror fan community, because it's utterly beyond me how that group can embrace and praise a great writer like Thomas Ligotti, while doing the same to someone like Keene. The Rising is an award-winning book, for God's sake. Horror fans, by and large, seem to be completely unable to tell good writing from bad, and I'm getting a little fed up with it.

Although, hey, here's something interesting. One of the authors who provided a blurb for The Rising is Richard Laymon. "A top-notch horrifying thriller!" he proclaims. Except that The Rising was first published in 2003, and, erm, Richard Laymon died in 2001. So...I don't really...

Hm.

Labels:

Brian Keene,

Horror,

Richard Laymon,

The Rising,

Thomas Ligotti

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

The Kind of Face You SLASH!!: Day 28 - The Nightgown Wraiths

Guess what I went and did? I left the book containing today's horror selection at work. Fortunately, I had finished the story, so I can write about it, but unfortunately I don't have it here in front of me for reference. Or to quote from. So this one will probably be pretty short.

Guess what I went and did? I left the book containing today's horror selection at work. Fortunately, I had finished the story, so I can write about it, but unfortunately I don't have it here in front of me for reference. Or to quote from. So this one will probably be pretty short.The story -- another long one -- is "Mr. Dark's Carnival", by Glen Hirshberg. Hirshberg is what is known as a "rising talent" in the genre: he's in his early forties and has a mere three books to his name, but he's raked in a healthy portion of award for his short fiction, and has earned praise from the likes of Peter Straub, Ramsey Campbell, and others. Campbell, in his introduction to Hirshberg's collection The Two Sams (from which "Mr. Dark's Carnival" is taken), compares him to M. R. James and Thomas Ligotti. Well then.

As it happens, earlier this year I read Hirshberg's novel, The Snowman's Children. That novel is more of a coming-of-age thriller -- a genre designation I may have just now coined, but which has a long history anyway -- than a horror novel, but I found it to be pretty skillful and intriguing, if a little too earnest. Hirshberg has really made his name with his short fiction, however, which I've always gathered is firmly and unquestionably horror, so I figured now was a swell time to dive in.

I was hestitant to pick "Mr. Dark's Carnival", as the title seems to hint that it's some sort of reflection on Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes, and, since I've never read that book (I should really stop admitting that sort of thing), I didn't want to read a 40-plus-page story that I wouldn't be able to fully appreciate. But Ramsey Campbell, in his introduction, said that the story deeply explored why readers and writers are drawn to fear, why we seek it out (or something like that), and considering that we're at the tail end of this horror project, I thought the story might be especially appropriate.

So here's what the story's about. In a small town in Montana, a college history professor named David Roemer is winding up his annual Halloween lecture, which deals with a bit of local legend. Back in the day's of America's Western expansion, and before Montana was officially a state, a man named A

l...bert? See, this is the problem with not having the book in front of me. Well, whatever. We'll go with Albert. Anyway, a man named Albert Dark took residence in this little town, and became judge. Apparently, for the most part, he was a pretty lenient judge. But on four different occasions, during his many years as judge in that town, posses hauled men who they claimed had committed some sort of crime to Dark's home, demanding swift justice. On each of these four occasions, the judge complied, with the stipulation that before the man was to hang, he would spend his final night in the judge's home, and, when the time came, Judge Dark himself would do the hanging.

l...bert? See, this is the problem with not having the book in front of me. Well, whatever. We'll go with Albert. Anyway, a man named Albert Dark took residence in this little town, and became judge. Apparently, for the most part, he was a pretty lenient judge. But on four different occasions, during his many years as judge in that town, posses hauled men who they claimed had committed some sort of crime to Dark's home, demanding swift justice. On each of these four occasions, the judge complied, with the stipulation that before the man was to hang, he would spend his final night in the judge's home, and, when the time came, Judge Dark himself would do the hanging.From this grew a legend of a place called "Mr. Dark's Carnival", which was actually one of those haunted house attractions that go up around the world every Halloween. This legend is not gone into specifically, beyond the fact that there were apparently unusual invitations to the haunted house issued. But Professor Roemer claims that such a place never existed, that it is in fact only a legend.

Towards the end of his lecture, he gets word that a troubled former graduate student of his has committed suicide. This man's girlfriend, Kate, was also one of Roemer's former students, as well as one of his former lovers. He goes to comfort her, and, long story short, comes across an invitation to Mr. Dark's Carnival. Which he and Kate excitedly attend.

Frankly, I don't quite know what Campbell was on about in his introduction. All this story really explores is why people go to haunted house attractions, which is, if not self-evident, at least uninteresting. As you can probably guess, Roemer and Kate make it to the carnival, and find it far more elaborate and bizarre and intriguing than they'd hoped it would be. And as you can probably also guess, there are really only two ways this thing can end, and, again, neither one is

all that exciting. I was really struck by how ordinary this story was. Not bad, just ordinary. This, from Glen Hirshberg, who, of the genre's new breed of talent, is one of horror's most respected torch-bearers. I mean, really, Glen Hirshberg? A haunted house attraction on Halloween that might actually really be haunted?? I just don't know what to say. I enjoyed it. It would be a nice campfire story, if you took out all the stuff that doesn't lead anywhere, which would be about half of it. But "Mr. Dark's Carnival" is the definition of "nothing special".

all that exciting. I was really struck by how ordinary this story was. Not bad, just ordinary. This, from Glen Hirshberg, who, of the genre's new breed of talent, is one of horror's most respected torch-bearers. I mean, really, Glen Hirshberg? A haunted house attraction on Halloween that might actually really be haunted?? I just don't know what to say. I enjoyed it. It would be a nice campfire story, if you took out all the stuff that doesn't lead anywhere, which would be about half of it. But "Mr. Dark's Carnival" is the definition of "nothing special".For instance, the subplot about the troubled ex-student who committed suicide seems poised to supply some unusual pay-off, either thematically or narratively, but all it does is provide the explanation for a rather tired twist at the end. What's ironic about the by-the-numbers quality of this story (which, in all fairness, is not a weakness from which Hirshberg's The Snowman's Children suffers) is that throughout Roemer's journey through the fake-or-is-it haunted house, any time he's not suitably impressed with what he takes to be effects or clever bits of misdirection, he expresses his disappointment about some standard bit of haunted house business that he's seen too many times in his life to count. Was Hirshberg not aware that he was practically begging his readers to make similar complaints about his story? Was that part of his point? I really don't think it was, and I'm left just feeling befuddled.

And remember when I said that one of the drawbacks of The Snowman's Children was that it was too earnest? Well, this next complaint is connected to that, although I'm not sure "earnest" is the right word here. But at one point, Roemer actually says the following:

Walking through a haunted house properly is a lot like making love.

Okay, well, that just about shreds it. If he'd said "Walking through a haunted house properly is a lot like fucking", I might have respected him more.

All right, well, that was a major disappointment, which is an odd thing to say about a story that isn't actually bad. When considered with other horror stories that revolve around Halloween night and haunted houses, it works perfectly well. I was just expecting more. I'm nowhere near done with Hirshberg -- not even close, really -- but I'll adjust my expectations accordingly next time.

Okay, well, that just about shreds it. If he'd said "Walking through a haunted house properly is a lot like fucking", I might have respected him more.

All right, well, that was a major disappointment, which is an odd thing to say about a story that isn't actually bad. When considered with other horror stories that revolve around Halloween night and haunted houses, it works perfectly well. I was just expecting more. I'm nowhere near done with Hirshberg -- not even close, really -- but I'll adjust my expectations accordingly next time.

Tuesday, October 28, 2008

The Kind of Face You SLASH!!: Day 27 - Dust in the Balance

H. P. Lovecraft and Algernon Blackwood were rough contemporaries -- Blackwood's writing career got started a bit before Lovecraft's -- and the former author was a great admirer of the latter. Of Blackwood, Lovecraft said:

H. P. Lovecraft and Algernon Blackwood were rough contemporaries -- Blackwood's writing career got started a bit before Lovecraft's -- and the former author was a great admirer of the latter. Of Blackwood, Lovecraft said:Of the quality of Mr. Blackwood's genius there can be no dispute; for no one has ever approached the skill, seriousness, and minute fidelity with which he records the overtones of strangeness in ordingary things and experiences.

Not only that, but check out that name! Algernon Blackwood! That is friggin' nuts! With that name, Blackwood had, by my count, only two viable career choices: horror writer, or malevolent super-scientist, the kind who rides around in zeppelins, commanding his zombie army via remote control. And it was his real name, too. It's not like he was born "Sidney Loomis", and traded up to "Algernon Blackwood" when he turned eighteen. No, that was his name out of the gate -- although, regrettably, his middle name was Henry.

But anyway. Blackwood's fiction, though it has remained in print (off and on, I would imagine) since his death, never took hold in the popular psyche the way Lovecraft's did. If you want to know why exactly that is, I'm not the guy to ask, although my knee-jerk, horror-snob answer is that Blackwood was by far the better writer. I don't really know what that means, though, and I don't actually believe it. That is, I don't believe that's why Blackwood's work is obscure, compared to Lovecraft; however, I do believe -- based, admittedly, on scant evidence -- that Blackwood was a far superior writer.

Thus far, I've read one Blackwood story (finished mere minutes ago), the nearly-novella-length "The Willows". In it, an unnamed narrator and his friend, known only as "the Swede", are traveling down the Danube by kayak. Due to flooding and fierce winds, they suffer what seems

to be a mild shipwreck on a small island somewhere in East Jesus, Hungary. Their kayak is undamaged, they have plenty of provisions, and so, not at all put out, they decide to make camp on this tiny island, which is covered, not incidentally, with willows.

to be a mild shipwreck on a small island somewhere in East Jesus, Hungary. Their kayak is undamaged, they have plenty of provisions, and so, not at all put out, they decide to make camp on this tiny island, which is covered, not incidentally, with willows.Early on, they they see a couple of fairly strange things. One is an otter, swimming along the river, which, at first glance, they mistake for a human body. Shortly thereafter, they see, in the distance, a man in a boat, who at first seems to be signaling to them, but whose motions they eventually decipher as the man making the Sign of the Cross.

Still dealing with very strong winds, the two men decide to take to the river again the next morning. That night, the narrator takes a little walk, and begins to feel extremely uneasy about the island, the willows, and the general surroundings:

But my emotion, so far as I could understand it, seemed to attach itself more particularly to the willow bushes, to these acres and acres of willows, crowding, so thickly growing there, swarming everywhere the eye could reach, pressing upon the river as though to suffocate it, standing in dense array mile after mile beneath the sky, watching, waiting, listening. And, apart quite from the elements, the willows connected themselves subtly with my malaise, attacking the mind insidiously somehow by reason of their vast numbers, and contriving in some way or other to represent to the imagination a new and mighty power, a power, moreover, not altogether friendly to us.

This "attack" will increase in strength and continue unabated until the end of the story. The narrator -- and eventually the Swede -- begin to see things at night, in the willows, that inspire a kind of awe-struck horror, and they begin to hear a sort of gonging sound that seems to come from everywhere at once, and which "defies description". These incidents, mixed with mysterious damage to their kayak and depletion of their food, works on the men's minds. The Swede appears to be more sensitive to their new, terrifying reality -- to what it is and what it means -- and together the two men come to understand this small island as a kind of intersection of two realities: the world as we know it, and another world, filled with beings whose purpose is grim on a cosmic and metaphysical scale, a scale so large that it is impossible to understand, however much the men might desperately crave understanding:

An explanation of some kind was an absolute necessity, just as some working explanation of the universe is necessary -- however absurd -- to the happiness of every individual who seeks to do his duty in the world and face the problems of life. The simile seemed to me at the time an exact parallel.

This is an essential passage, I think, because it is the core of what Blackwood is writing about, his specific reason for writing horror, which is the great doubt every human being, no matter how confident they are in their own view of the universe, has at some point, that not only is there no benevolent God, but there is no comfort in our existence. There is only pain and horror and despair and meaningless suffering. Everything else is just a mask. Or -- and this may be closer to the point -- if there is a force governing the universe, it is malignant. This is what Thomas Ligotti is writing about, and it's what many claim Lovecraft is writing about as well, although it's hard, sometimes, for me to see it in his work.

And it doesn't matter if you're an atheist (the atheists I know have a much warmer view of the universe than this), and it doesn't matter if you firmly believe in God. It doesn't even matter if your belief in God is some day proven correct. All that matters is that you also sometimes see things Blackwood's way, that you harbor that fear, however mildly, and however rarely. If you do -- and you do -- then "The Willows" will make its mark on you.

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

The Kind of Face You SLASH!!: Day 14 - The Nightmare of the Organism

I'm not really sure where Thomas Ligotti came from. I don't mean geographically, because who cares, and I don't mean who influenced him, because over the years Ligotti has been very clear about that (for the record, Poe, Lovecraft and Thomas Bernhard are high on that list). I mean, where was he first published, who first noticed him? How did he break through the wall of miserable 1980s and 90s horror fiction to become someone who is deservedly recognized not only as one of the best horror writers alive, but one of the best who has ever lived?

I'm not really sure where Thomas Ligotti came from. I don't mean geographically, because who cares, and I don't mean who influenced him, because over the years Ligotti has been very clear about that (for the record, Poe, Lovecraft and Thomas Bernhard are high on that list). I mean, where was he first published, who first noticed him? How did he break through the wall of miserable 1980s and 90s horror fiction to become someone who is deservedly recognized not only as one of the best horror writers alive, but one of the best who has ever lived?I don't know. I know that he started publishing his stories in small press magazines in the 1980s, and he developed a cult following. And that's about it. Eventually, he had compiled enough stories to start publishing books. His first three -- Songs of a Dead Dreamer, Grimscribe and Noctuary -- were published by Carroll & Graf as mass market paperbacks. I used to buy a lot of genre fiction put out by Carroll & Graf in those days, and I remember they cost about $4.99. Now, used on Amazon, those three books run between $25 and $35 each. Not bank-breakers, maybe, but it shows that those books are definitely in demand.

Ligotti has said that he feels that he's one of the few genuine horror writers out there today, because it's the only genre he works in, he has no interest in writing anything else. He's drawn to horror because of what he views as its main potential (from an excellent interview that I commend to everyone's attention):

I think there’s a great potential in horror fiction that isn’t easily available to realistic fiction. This is the potential to portray our worst nightmares, both private and public, as we approach death through the decay of our bodies. And then to leave it at that—no happy endings, no apologias, no excuses, no redemption, no escape...