Ingmar Bergman’s

The Serpent’s Egg begins with a gray image of people marching towards doom. We might think, at first, and depending on our knowledge of the film’s subject, that these people are Jews, possibly being rousted from a ghetto, or herded to a gas chamber (and that is where this film is heading, though Bergman ends his story before it gets there). But these miserable people, shown in clips throughout the very Woody Allen-esque opening credits, which are played over cabaret jazz, are in fact the people who will either actually carry out the Holocaust, or will facilitate it through their indifference, fear and callousness.

The Serpent’s Egg is set in Berlin, in 1923. Abel Rosenberg (David Carradine), the film’s protagonist (“hero” seems like the wrong word), is an American Jew who has been living in Berlin with his brother Max for the last three years. With Max’s ex-wife, Manuela (Liv Ullmann), the brothers formed a circus trapeze act, until Max hurt his wrist. Since then, Max and Manuela have divorced, and both Max and Abel have descended into a kind of nightmare depression, which Abel dulls with alcohol, and which Max ends, at the beginning of the film, with suicide. After meeting with the police, in the form of Inspector Bauer (Gert Frobe), Abel goes to the cabaret where Manuela works to inform her of Max’s death. He shows her Max’s suicide note, and she stares at it uncomprehendingly, saying it is completely illegible. She asks Abel to try to read it, but he can only make out one line: “

There is poisoning going on.”

That line is, really, the film. Bergman’s vision of 1920s Germany is one of endless grotesquerie and madness, one where an evil is growing quietly from within. Those who are not directly linked to the creation of Germany’s monstrous future, like Abel and Manuela, can only suffer through the country’s devastating poverty and try to make their way, while either choosing to ignore, or smile their way past, what they see going on around them, as Manuela does, or let the nightmare consume them, which is the route that Abel chooses, for a while. He gets drunk every night, and later in the film, when he’s moved in with Manuela, he complains that a noise from outside their room, the rumbling of an engine, is “driving him wild”. Manuela can’t hear the engine, unless he mentions it, and then she can almost make it out. This is because Abel is tuned into the great and Hellish machine that’s revving to life beneath them, because he knows the world is about to end in fire. Manuela secretly knows the same thing, but tries to forget it. And it’s the knowledge, not the sound, which drives Abel wild. Berlin’s upper classes pursue their decadence with a forced and manic joy, but the wildness of Abel’s knowledge drives him to pursue similar diversions the same way he pursues waking up in the morning, which is to say: grimly. Abel throws a brick through the window of a Jewish shop, and humiliates a fellow patron at a brothel he visits late in the story, a scene which ends with him hitting one of the prostitutes – such are his tools for dealing with the engine.

Before going any further, it should be noted that Carradine is a spectacularly weird choice for a lead in a Bergman film. His gaunt, old-before-its-time face and mopey eyes are just right for Abel, and in that sense he’s not unlike Bergman favorite Max von Sydow, but his line delivery can sometimes seem over-pronounced (Carradine’s excuse -- given on the commentary track – that Abel is an American surrounded by Europeans, and that’s how people often speak to foreigners, doesn’t quite fly with me) and carry only the weight that the words had as originally written, but no more. And his drunk walk, which he performs regularly over the course of the film, is of the exaggerated, 1930s comic hobo variety. When faced with Nazi atrocities while stumbling down the street, I kept expecting him to stop, rub his eyes, look at the half-full bottle in his hand, and then pitch the bottle to the side.

“Drunk” and “sad” aren’t the only things Carradine has to do, however, due to the fact that Abel is not an entirely passive victim -- he

nearly is, but not quite – because

The Serpent’s Egg has a structure that is unique, in my experience, in Bergman’s work. It flows like a mixture between a mystery story and a horror film, with the emphasis on the latter. In its basic narrative line,

The Serpent’s Egg most resembles horror films like

Angel Heart (itself a horror film mixed with detective fiction) and

The Ninth Gate, the kind where the hero follows a set of clues that lead him from a dark crime to a darker, often occult, revelation that either destroys him or at least opens his eyes to the broad-spanning and evil truth at the heart of his society, or the secret mad powers that will tear that society apart.

As I say, these stories are told as mysteries, and end up in the horror genre based, generally, on what is discovered. The beginning of this mystery is the suicide of Abel’s brother Max, although given the relentlessly grim nature of Bergman’s film, it’s less surprising that Max, who we only ever see as a corpse, blows his brains out than that everybody else in Berlin doesn’t follow his example. The mystery is deepened, however, when Inspector Bauer calls Abel to the morgue to show him a series of corpses, asking, after revealing the face of each body, if Abel knows them. A couple he knew in passing, one female was engaged to his brother, and another reminds Abel of his father. It appears at first, to Abel and to us, that Bauer is looking at Abel as the killer of all of these people, so it would appear that, along with everything else, Bergman is setting Abel up as a “wrong man” figure. But Bauer’s suspicions, if he ever even had them, ultimately go nowhere. In any case, when Abel clues into these suspicions, he accuses Bauer of doing this because he, Abel, is Jewish. This stops Bauer cold, which Abel takes as confirmation that he was right.

Another staple of the various genres Bergman is poking around with is the former acquaintance of the protagonist, now the villain of the story. In this film, that man is Hans Vergerus (Heinz Bennent), who Abel runs into, for the first time in ten years, in the wings of the stage at Manuela’s cabaret. He begins peppering Abel with questions about their mutual past, but Abel acts as though he doesn’t know him. Later, Abel tells Manuela that when he and Hans were children, Hans tied a live cat down and dissected it. He describes seeing its heart still beating very fast. This incident, not surprisingly, has lingered with him, possibly in the back of his had as an indicator of the future, or as a clue to the world’s infernal secrets. It’

s certainly a clue to the character of Vergerus, who he will meet again, and learn more about. Among other things, Manuela has a menial day job in Vergerus’s clinic, and Abel eventually will, too, in the clinic’s archives.

All of this is leading us to the solution of a mystery – to be honest, Abel, in his role as the protagonist, isn’t much of a seeker of facts, but he does have a talent for stumbling across them. And he trips face first into the truth when he returns one morning, from the brothel mentioned earlier, to the room he shares with Manuela, and discovers her dead. Here, also, Bergman’s sense of logic shatters – deliberately, I’d guess -- along with all the mirrors that Abel breaks in the room, revealing behind each one a camera. In a scene that seems to challenge us to locate ourselves within any kind of physical geography that pertains to what we’ve seen, or thought we knew, before, Abel climbs into one of those hidden camera rooms and finds himself running around a subterranean series of rooms, filled with metal walls, metal staircases, and metal bars (in fact, it looks not unlike his work area at the clinic’s archives). We realize, before Abel does, that someone is following him through these rooms, and finally attacks him – and, due to the way the subsequent fight is shot, we never see the assailant’s face. The fight ends on an elevator, with the attacker being decapitated, and the horror film feeling Bergman has been toying with all along is now put in the forefront.

The motives of the man behind all this, Vergerus, might be considered muddy. The human experiments he’s been conducting – which, like the similar Nazi experiments that followed in reality, result always in torture, and often in death – are intended to indicate what is weak about humanity, and what is strong, so that the weak can be eliminated. How injecting a man with a drug that causes him to endure unbearable dread until he’s driven to suicide is supposed to indicate what’s weak about humanity is anybody’s guess, but Vergerus’s methods aren’t exactly that far-removed from those of the Nazi scientists he, in Bergman’s world, gave birth to. And unclear motives are simply something you have to come to terms with when considering Nazi atrocities. The genocide they perpetrated wasn’t just genocide (but then, genocide never is); these atrocities included, in some cases, turning their victims into furniture. Such acts inspired several generations of serial killers, so, with the Nazi Germany, what you have, at the core, is serial murder on a national scale. Horror film tropes and general illogic might be the best approach to a fictional tale of the Holocaust or its beginnings, even if your style is intended to be naturalistic, which Bergman’s isn’t.

The horror idea is carried further in the film’s climax, which features Vergerus swallowing a cyanide capsule. He says he knows Bauer is on to him – these experiments aren’t yet sanctioned by the government – so he takes the capsule without regret, knowing that what he has helped set in motion is much bigger than anyone’s romantic ideas of justice. Just before the cyanide takes effect, Vergerus positions

a bright light over his head, and holds a mirror to his face, so he can clinically observe the way the muscles in his face distort as the poison shuts down his body. This is a psychopathology so far removed from any sense of human worth and dignity, and so dedicated to its idea of a better world, that when the pathology grows, and cracks its shell and steps fully formed to take its place in the world, the option -- for those among us normal enough to regard the serpent with an overwhelming incredulity -- of going mad right along side it might seem, must

have seemed, awfully tempting. You can’t beat, or reason with, or argue with, or feel superior to, or react to in any rational way, that which you have no hope of understanding.

In his autobiography,

The Magic Lantern, Bergman says of

The Serpent’s Egg:

If I had created the city of my dreams, a city that does not exist and never has, and yet manifests itself acutely with smells and loud sounds, if I had created that city, not only would I have been moving in it with total freedom and an absolute sense belonging, but also, more important, I would have brought the audience with me into an alien but secretly familiar world. In The Serpent’s Egg, however, I ventured into a Berlin that nobody recognized, not even I.I pulled that quote from the internet, not the book itself, so I don’t have the context necessary to tell me if Bergman thinks the result was good or bad, although the tone implies that he had regrets. The film is generally regarded, in truth, as one of Bergman’s worst, and it’s true that there are hiccups along the way – when Abel tells a prostitute to “

Go to hell!”, and the prostitute laughingly responds “

Where do you think we are?”, it’s hard to believe that Bergman didn’t know that he’d already made that point several times over – but I really don’t think his Berlin is one of them. The desperate decadence we associate with the country at that time is all there, to the point where it seems like, as shown by the bizarre, but not unfamiliar, cabaret acts in Manuela’s club, even Germany’s distractions were insane. The madness of the society is so deeply rooted that the entertainments available are grotesque enough to be slightly removed from humanity, which will be necessary to do the work asked of them some ten or fifteen years later. At one point, Inspector Bauer sees a street musician, the kind with an accordion and a monkey, performing with a blank faced to a crowd of people just as dull-eyed as he. Although Bauer is actually a fairly sympathetic character, the way he makes a point to give the musician money seems to say, “Keep it up. You’re doing good work.”

Humanity isn’t completely dead in Bergman’s Berlin – it’s just dying. Manuela clings to it, smiling sometimes insanely, and Ullmann’s performance, considered shrill by some, I think is hysterical in just the right way. Manuela is a fundamentally decent person, one of the few left in her world who can still feel guilt, which she does, over Max’s suicide. In one of the film’s best scenes, she goes to see a Catholic priest, played with a kind of simple warmth by James Whitmore. The priest is at first dismissive of her, based on her inability to come to the point, but when she does, and he sees that she wants forgiveness for something she most likely isn’t even guilty of, his wall of apathy crumbles, and he tells her that God is so remote that he probably can’t even hear our prayers for forgiveness. But, on His behalf, he, the priest, will forgive her, and ask her forgiveness in return, for his previous indifference, which she grants. In Bergman’s long battle with God, here he seems to allow for the possibility, at least, of His existence; he just doesn’t see what good that existence does anybody. But at least two of His believers, Manuela and the priest, seek and bestow forgiveness. There won’t be much more of that in the years ahead, so you take what you can get.

When the film ends, we’re told by Inspector Bauer that Hitler’s Munich putsch has failed completely. Vergerus has already predicted this to Abel, and said that Hitler was a dullard, and would not be the future of Vergerus’s dream. Little does he know, although this low opinion of Hitler as an intellect might tie in with the film’s title, which

supposedly comes from this line from Shakespeare’s

Julius Caesar:

And therefore think him as a serpent's egg

Which hatch'd, would, as his kind grow mischievous;

And kill him in the shell.

But that’s not what happened, is it? And as it pertains to The Serpent’s Egg, the line comes off as an optimistic fantasy, because you read the words “kill him in the shell” and you have to think: if only.

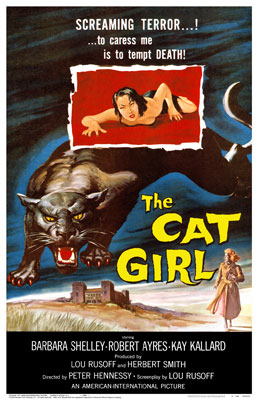

Why not? It looks staggeringly original, it's got a girl in it, and a cat. Plus that Asian girl is looking all slinky in the part of the poster that was ripped out to reveal her red...attic? Basement? Probably not her kitchen. But she's slinky, is what my point is.

Why not? It looks staggeringly original, it's got a girl in it, and a cat. Plus that Asian girl is looking all slinky in the part of the poster that was ripped out to reveal her red...attic? Basement? Probably not her kitchen. But she's slinky, is what my point is.

JCVD (d. Mabrouk El Mechri) - When I first heard of this post-modern, heart-laid-bare action film, which features Jean-Claude Van Damme as a version of himself, I though it must be some kind of disaster. What happens is, Van Damme -- frustrated over his divorce, loss of custody of his daughter, and the trajectory of his career -- goes to a bank in Belgium, and finds himself in the middle of a robbery. Due to an unfortunate mix-up, the police believe him to be the guy robbing the bank, which, for the safety of those inside, Van Damme goes along with. As a crime film (which this is, more than it is an action film), JCVD is a little too loose for my tastes, but Van Damme is the real point of the movie. To put it simply: I had no idea. And it's not just his now-famous tortured monologue, delivered to the camera, and to his fans -- throughout the film, he's so effortlessly moving as a 47 year-old guy, whose career is that of an action film star, and who now believes that his career is not only kind of silly, but maybe worthless, too. He said it, not me, but if Van Damme really thinks that he's never done anything worthwhile with his career, he can think again.

JCVD (d. Mabrouk El Mechri) - When I first heard of this post-modern, heart-laid-bare action film, which features Jean-Claude Van Damme as a version of himself, I though it must be some kind of disaster. What happens is, Van Damme -- frustrated over his divorce, loss of custody of his daughter, and the trajectory of his career -- goes to a bank in Belgium, and finds himself in the middle of a robbery. Due to an unfortunate mix-up, the police believe him to be the guy robbing the bank, which, for the safety of those inside, Van Damme goes along with. As a crime film (which this is, more than it is an action film), JCVD is a little too loose for my tastes, but Van Damme is the real point of the movie. To put it simply: I had no idea. And it's not just his now-famous tortured monologue, delivered to the camera, and to his fans -- throughout the film, he's so effortlessly moving as a 47 year-old guy, whose career is that of an action film star, and who now believes that his career is not only kind of silly, but maybe worthless, too. He said it, not me, but if Van Damme really thinks that he's never done anything worthwhile with his career, he can think again. Les Biches (d. - Claude Chabrol) - This film has been on my radar for at least a decade, maybe more, beginning before my knowledge of films was even that deep, because, hey, lesbians. Of course, that kind of content is pretty meager, probably because I just can't win, but Chabrol's highly influential, quiet thriller about two women -- the rich Frederique (Stephane Audran) and the poor, withdrawn Why (Jacqueline Sassard) -- is fascinating in the way it subverts our ideas of who will snap, and the reasons behind it. If you've never seen a Chabrol film, but have read the novels of Ruth Rendell, you'll already be familiar with the sensation of coldly watching a group of people -- who, for the good of all, should have never even met -- coming together like a car-less traffic accident. Quietly, coolly, and perversely compelling.

Les Biches (d. - Claude Chabrol) - This film has been on my radar for at least a decade, maybe more, beginning before my knowledge of films was even that deep, because, hey, lesbians. Of course, that kind of content is pretty meager, probably because I just can't win, but Chabrol's highly influential, quiet thriller about two women -- the rich Frederique (Stephane Audran) and the poor, withdrawn Why (Jacqueline Sassard) -- is fascinating in the way it subverts our ideas of who will snap, and the reasons behind it. If you've never seen a Chabrol film, but have read the novels of Ruth Rendell, you'll already be familiar with the sensation of coldly watching a group of people -- who, for the good of all, should have never even met -- coming together like a car-less traffic accident. Quietly, coolly, and perversely compelling.

“Drunk” and “sad” aren’t the only things Carradine has to do, however, due to the fact that Abel is not an entirely passive victim -- he nearly is, but not quite – because The Serpent’s Egg has a structure that is unique, in my experience, in Bergman’s work. It flows like a mixture between a mystery story and a horror film, with the emphasis on the latter. In its basic narrative line, The Serpent’s Egg most resembles horror films like Angel Heart (itself a horror film mixed with detective fiction) and The Ninth Gate, the kind where the hero follows a set of clues that lead him from a dark crime to a darker, often occult, revelation that either destroys him or at least opens his eyes to the broad-spanning and evil truth at the heart of his society, or the secret mad powers that will tear that society apart.

“Drunk” and “sad” aren’t the only things Carradine has to do, however, due to the fact that Abel is not an entirely passive victim -- he nearly is, but not quite – because The Serpent’s Egg has a structure that is unique, in my experience, in Bergman’s work. It flows like a mixture between a mystery story and a horror film, with the emphasis on the latter. In its basic narrative line, The Serpent’s Egg most resembles horror films like Angel Heart (itself a horror film mixed with detective fiction) and The Ninth Gate, the kind where the hero follows a set of clues that lead him from a dark crime to a darker, often occult, revelation that either destroys him or at least opens his eyes to the broad-spanning and evil truth at the heart of his society, or the secret mad powers that will tear that society apart.

When the film ends, we’re told by Inspector Bauer that Hitler’s Munich putsch has failed completely. Vergerus has already predicted this to Abel, and said that Hitler was a dullard, and would not be the future of Vergerus’s dream. Little does he know, although this low opinion of Hitler as an intellect might tie in with the film’s title, which

When the film ends, we’re told by Inspector Bauer that Hitler’s Munich putsch has failed completely. Vergerus has already predicted this to Abel, and said that Hitler was a dullard, and would not be the future of Vergerus’s dream. Little does he know, although this low opinion of Hitler as an intellect might tie in with the film’s title, which

* * * * *

* * * * *

Tom Reagan

Tom Reagan  Sherlock Holmes (as portrayed by Jeremy Brett)

Sherlock Holmes (as portrayed by Jeremy Brett) Oh ha ha, no, is not true. I am not balloons. You are April fools! Good night my friend!

Oh ha ha, no, is not true. I am not balloons. You are April fools! Good night my friend!