Showing posts with label Viggo Mortensen. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Viggo Mortensen. Show all posts

Monday, September 15, 2014

The Cronenberg Series Part 15: Another Thing, in Another Country

In 1889, a London newspaper called the Southern Guardian printed an editorial concerning the Jack the Ripper murders, crimes which at that time would have still been fresh but also dormant long enough to allow for some reflection. The editorial contains this passage:

Suppose we catch the Whitechapel murderer, can we not, before handing him over to the executioner or the authorities at Broadmoor, make a really decent effort to discover his antecedents, and his parentage, to trace back every step of his career, every hereditary instinct, every acquired taste, every moral slip, every mental idiosyncrasy? Surely the time has come for such an effort as this. We are face to face with some mysterious and awful product of modern civilization.

Over a century later, Alan Moore would take this basic idea and run with it in From Hell, the exemplary comic book about the Ripper murders (plus loads else) he created with artist Eddie Campbell. A quote attributed to Moore (the question of who said this first is somewhat unsettled, but anyway) in relation to From Hell and Jack the Ripper goes so far as to claim the Ripper "gave birth to the 20th Century." In the comic itself, this idea appears as a revelation spoken by Jack the Ripper to his carriage driver: "It is the beginning, Netley. Only just beginning. For better or worse, the Twentieth Century. I have delivered it." This doubtlessly gives Jack the Ripper far too much credit but it's a powerful idea, especially if you're an extremely pessimistic sort of person.

Anyway, the power of the idea doesn't have to rest in Jack the Ripper specifically. If you want to look at where we find ourselves today ("we" as a species, and as the only agents of history that care to regard themselves as such), and regardless of your individual politics or philosophy or theology I think we can pretty much all agree that where we are is describable as "not good," the impulse to trace it all, all of this, to a certain point, a specific moment, a thing, or cluster of things, or even a thought, can be irresistible. And such is the pull of A Dangerous Method, a late career masterpiece for David Cronenberg and screenwriter Christopher Hampton. The film, based on Hampton's play The Talking Cure and John Kerr's non-fiction book A Most Dangerous Method, pins the birth of the 20th Century as we understood and experienced it, and which in turn gave birth to today, right near its beginning -- in 1904, in Zurich. The key figures over the course of the film, which will stretch until 1913, a not insignificant year, are Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender), at this time, 1904, a young psychiatrist who is fascinated by the new methods of psychoanalysis developed by Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen), who he hasn't met yet, but will, and the young patient Sabina Spierlein (Kiera Knightley), who, in Cronenberg's typical "let's get to it" fashion, Jung begins treating scant minutes after A Dangerous Method has begun.

Sabina, a bundle of extreme physical tics that serve to put on display the deep shame and anger she feels as a result of her somewhat off-center sexual desires, is extremely intelligent, so intelligent in fact that despite her desperate unhappiness ("There is no hope for me," she says) she is fascinated by her own mental illness, and the mental illnesses of others. This leads Jung to take her under his wing, and to encourage her to pursue a career in psychiatry. She assists him in psychoanalytical experiments, such as testing the concept of word association on Jung's own wife, Emma (Sarah Gadon), and interprets the subsequent answers with unsettling perception. Sabina and Jung become so close, in fact, that Cronenberg wants us to make no mistake: when Jung first visits Freud in Zurich, he arrives with Emma. When their meeting is done, the next scene shows Jung walking down in the street in conversation with Sabina. Some members of the audience (I'm talking about me here) might find themselves trying to remember which one he actually when to Zurich with. Emma and Sabina are becoming the same in his mind, though he doesn't know it, or won't acknowledge it. The difference is, Emma is the one he impregnates.

Because yes, soon Jung and Sabina are having sex. But first, to be clear about where we stand: Jung, an Aryan doctor, is treating a Jewish woman suffering from a deep sexual repression that has led to a mental breakdown. Jung's mentor is Freud, a Jewish doctor who watches his independently wealthy protégée waltz through his life and career with little worry, so oblivious that it's beyond Jung why Freud's Jewishness might be an obstacle in Freud's theories of psychoanalysis gaining any traction among the European establishment. It is beyond Freud how this could be beyond Jung. Jung's major criticism of Freud's interpretation of the human mind and subconscious is that it is exclusively focused on the sexual ("There must be more than one hinge into the universe," he says to Sabina). Freud, in turn, is frustrated, on the surface, by Jung's drifting into mysticism -- Jung wants to study telepathy, he believes he can sense what's coming in the near future, etc. -- but of course at root what frustrates Freud is Jung's naïveté. In any case, Freud certainly couldn't have foreseen the consequences of sending into Jung's care another psychiatrist, Otto Gross (Vincent Cassel), a man whose instability is the opposite of Sabina's -- if anything, he's not repressed enough, and he encourages Jung, his Aryan colleague, to embark on the affair with the young Jewish patient Gross is quite certain is what Jung truly desires. That Gross is Austrian -- as he was in real life, as the real Sabina Spielrein really was Jewish, A Dangerous Method being, after all, "based on a true story," as they say -- is certainly neither here nor there. Certainly not in the early 1900s, before even World War I. Yet it's Jung, with his somewhat mystical and superstitious mind, who continually insists that he doesn't believe in coincidences.

Of course, as with most of us, it doesn't matter what Jung believes in. He's a great doctor, and a brilliant man, and throughout the film Cronenberg positions him as a keen, in his mind, observer -- passive too, up to a point, but that's part of the psychiatrist's job, after all -- anyway, sitting back, across the room, often behind the other person as he listens to them speak. But the point is, he misses everything. Despite how man hinges there are into the universe, he can't find them. About midway through the film, the key line is spoken to him by Sabina, and he doesn't understand it. This is not his fault, because given what it portends who could? But Jung is the mystic, so when Sabina, building off her reading of Wagner's treatment of the Siegfried myth in his Ring Cycle, says that she's developing the theory that "only the clash of destructive forces can create something new," he seems to miss out on every practical or immediately relevant, or even cosmically human, meaning those words might carry. When shortly thereafter Gross is pushing him into an affair with Sabina -- an affair she badly wants, because despite her obsessions she's had no sexual experiences of her own -- he doesn't even seem to recall what Sabina told him about their relationship, their opposite natures, among them being that she is a Jew and he an Aryan. "And other, darker differences," she said, which he wondered about at the time but then when that hinge to the universe that so preoccupies Freud swings his way, pfffft! Everything else leaves his brain.

Competing psychoanalytic theories presented in A Dangerous Method involve the reasonable repression of desire -- that's Jung (never mind how he actually behaves); Freud, in the context of the film, is noncommittal -- and the perhaps unreasonable pursuit of an pleasure one might desire. That's Gross. To cut to the chase, and considering the film's eventual implications, is it unreasonable to see Gross as the Teutonic will that will one day unleash Aryan dominance, powered by an untrammeled freedom to do as they wished, throughout Europe? Even Jung's occupation as a passive observer feels like the sometimes admired neutrality of the Swiss, until you consider sometimes what they're being neutral about. You can do it, you can stop it, or you can allow it to happen. Sabina, as unable to see into the future as anybody, loves Wagner's operas, and she asks Jung if he admires Wagner as well. Jung replies "The man and the music." Nowadays, with hindsight being so powerful, most people would only pick the second of those two things to admire, and of course even that perspective, justifiable as it unquestionably is, forces them to share an interest with Adolf Hitler.

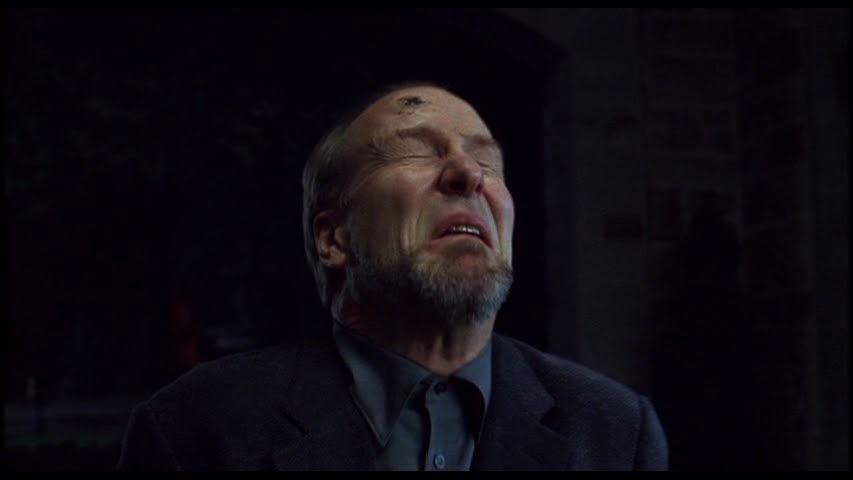

This film isn't about taking Carl Jung down a peg, however. Given the metaphorical nature of A Dangerous Method, it's actually quite difficult to view these characters as bearing much relation to the historical truth, no matter how accurately it depicts the events and personalities (I'll confess that I'm the wrong guy to ask about this). One of the ancillary interests Cronenberg and Hampton seem keen to pursue is their skepticism of "great men" -- Jung, of course, but also Freud, who, wiser than Jung though he can often appear, is nevertheless shown being envious of Jung's wealth (his wife's wealth, to be specific); even his ideas about human sexuality, which one might guess Cronenberg to be sympathetic towards, is skewered. Anyway, I think it's pretty funny when Freud tells Jung, after the latter has just related a dream about hauling around a giant log, "I think you should entertain the possibility that the log represents the penis." In fact, I'd go so far as the argue that Mortensen as Freud -- a strange bit of casting that I think nevertheless pays off quite nicely -- is giving an essentially comic performance. His occasionally sing-song delivery sharply but quietly illustrates Freud's condescending arrogance, and if Fassbender plays Jung as naïve and thoughtless, he's also open and generous. Mortensen plays Freud as free of those weaknesses, and those strengths.

Jung is still difficult to like, and after a while he's even difficult to admire. Fassbender's performance is a model of the kind of absence of judgment you often hear actors claim is essential to playing unsympathetic characters. Late in the film, Jung may have lived to regret some of his behavior, but for much of A Dangerous Method's run time the notion that his choices might actually be destructive would, if not exactly surprise him, be something he could rationalize. He could build a case in his own favor. His love for Emma -- genuine, I'd have to suppose -- would be his main argument for doing, or rather not doing, certain things, and he could even reasonably claim that the sexual relationship with Sabina, deeply unethical though it was, actually helped her. Two destructive forces -- Jung's entitled blundering and Sabina's erratic, sometimes violent madness -- clashed in deliberately painful sex, and created a brilliant woman who could put her inexperience behind her. Knightley, giving the performance of a lifetime, so exquisitely plays Sabina's wounds that the softening of her alarming harshness, and wild and ugly physical convulsions, that the mere quieting of these becomes incredibly moving (the real brilliance of Knightley's criminally underrated performance is that she never lets go of Sabina's peculiarities; she may be better, but some things are never gone, and Knightley holds on to that, beautifully). The pain her cure causes for others becomes acceptable. That's the positive reading.

But the rest of the 20th Century still has to be accounted for. The Aryan/Teutonic freedom Otto Gross celebrates and which Jung only pretends to want to restrain, is about to sweep through Europe. Cronenberg's fascination with the relationship between sex and death has never been so monumental in scope as the film he only hints would follow A Dangerous Method. Freudian psychoanalysis seeks to interpret the human mind and human behavior in terms of the drive for sex and towards death, and this method, the talking cure, was born at the conception and birth of the century. Sex can create -- Jung has many children with Emma -- and destroy, as it nearly did Sabina, as it to some degree seems to have destroyed Otto, at least as a functional person who could survive in civilized society, as it destroys Jung's sense of his own morality. It is a destructive force, one of Sabina's, and Wagner's, two destructive forces that clash and create something new. Psychoanalysis joined them, and the 20th Century was born. The film ends in 1913, the year before World War I. That's Death. In the years following this, in Berlin, Weimar Germany is now popularly remembered for its decadent nature. That's Sex. They joined in Freud and Jung, as personified by Sabina, they split into war and its desperate aftermath, and joined together again in 1939.

At the end of A Dangerous Method, Jung tells Sabina about a dream he had, one of an ocean of blood destroying a town. It was "the blood of Europe." Not, perhaps, Christopher Hampton's subtlest line, but it's interesting to note, as I circle back around, that in Moore and Campbell's From Hell, the conception of Adolf Hitler is actually depicted. Hitler would have been conceived in 1888, right in the middle, or thereabouts, of the Ripper killings. In one of Moore and Campbell's least subtle moments, this sex act between Alois and Klara is symbolized by an ocean of blood pouring out of a synagogue. That too, I'd say, counts as the blood of Europe. So the 20th Century is conceived, but according to Cronenberg and Hampton, it was born in the back of a carriage, with a doomed woman screaming, as though giving birth.

Sunday, August 24, 2014

The Cronenberg Series Part 14: He Is The Undertaker

This is sort of my way of saying that A History of Violence and Eastern Promises feel a little bit like an itch Cronenberg wanted to scratch, because even ten years later the influence of Pulp Fiction was in the air, and Cronenberg was aware of it, and intrigued. Plus, as non-genre writers like Richard Price who have taken very artistically profitable turns into the crime genre have noted, anything you might want to do creatively can be done within the structure of a crime story. Violence, as it happens, interests Cronenberg, as should probably be apparent now, and also in the air in 2005 was the changing nature of violence in action films. At the time of the release of A History of Violence, a new brand of brutal hand-to-hand combat choreography had been popularized by The Bourne Identity and The Bourne Supremacy; in those films, one person knows how to fight better than the other guy, and the fights don't last long. Though Cronenberg spoke somewhat dismissively of the Bourne films, their influence can be found in both A History of Violence and Eastern Promises. The main difference is than for Cronenberg, the acceptability of this kind of cinematic combat made some things easier for him, and unlike Doug Liman and Paul Greengrass, who'd directed the Bourne films, no one would expect Cronenberg to hold back, least of all himself. He wanted to deal with real violence -- which in truth he'd never really done before, the violence in his films prior to this being mostly fantastical in nature, in one way or another -- bluntly, and with his signature grotesqueness adapted to the crime scene.

What also happened was David Cronenberg found the actor who would be, and still could be, for him what, say, Robert DeNiro was for Martin Scorsese. Or, rather, what Leonardo DiCaprio currently is for Scorsese; that is, a very fine actor who happens to have the box office clout to help an aging but still extremely vibrant director get his films get made. Viggo Mortensen was pretty fresh off the Lord of the Rings trilogy, which made him a star. Mortensen, being who he is, cashed in by making three films in a row with David Cronenberg, a Western with director Ed Harris, a terribly bleak Cormac McCarthy adaptation, and so on. Mortensen hasn't been in the last two Cronenberg films (though he would have been in Maps to the Stars, Cronenberg's latest, however scheduling messed that up), but I hope they pair up again soon. Mortensen's ability to seem like both an ordinary man and an extraordinary one in the same film, even the same breath, his general, and genuine, strangeness, all were an immeasurable help in transitioning Cronenberg from the bizarre and the deranged into the relative realism of this pair of films. Although one of these could have used a little more help, which is I guess my way of finally getting started.

Based on a comic book by John Wagner and Vince Locke, with a screenplay by Josh Olson, A History of Violence is about a man named Tom Stall (Mortensen) who lives on a farm in rural Indiana with his wife Edie (Maria Bello), teenage son Jack (Ashton Holmes), and young daughter Sarah (Heidi Hayes). Tom owns a diner in town, and one night two ruthless criminals (Stephen McHattie and Greg Bryk, who we previously saw at the beginning of the film, leaving behind a pile of corpses, including a child, in a motel massacre) bulldoze into the diner. They're about to kill one of Tom's waitresses when something clicks in him and soon he's smashed one of them across the face with a coffee pot, scooped up a dropped gun, and pretty soon Tom, though wounded, has killed them both. His story hits the TV news, the evening papers, it's a story big enough to reach Philadelphia, where some gangsters get wind of it and think Tom Stall looks familiar. So Carl Fogarty (Ed Harris) and a couple henchman come to town, shadow Tom and call him "Joey," as in Joey Cusack, crazy violent Philly gangster who took out one of Fogarty's eyes with barbed wire. Is it possible that Tom Stall really is, or was, Joey Cusack? Of course it is, because otherwise the title A History of Violence would be meaningless. Maybe if it'd been called A History of Violence? some suspense could have been maintained on that count.

I suppose I should be blunt about this. Having seen A History of Violence several times over the last nine years, I have come to the conclusion that it's something of stumble, a film that is at once clumsy and lean, which makes for an odd mix though one that slightly recalls Cronenberg's earliest features. However, those films, like Shivers and Rabid, had the benefit of Cronenberg's immense and restless imagination. Even Spider, which he also didn't write, provided him with an expansive set of parameters. With A History of Violence, for the first time Cronenberg seems hemmed in by the ordinariness of it all -- said ordinariness includes the gangsters by the way.

Small town America does not rest easily alongside Cronenberg's aesthetic or philosophy. Josh Olson, I don't know about, and either way I'm grateful that the reaction to something Cronenberg is unfamiliar with is not to be condescending, patronizing, or insulting. The Indiana town where most of the film takes place is portrayed as regular, friendly, undramatic, save for that which would count as "every day" -- bullies and such. But Cronenberg is a filmmaker who turned down the opportunity to direct Witness because he felt no intellectual or philosophical connection to the Amish and therefore believed he would do a bad job. I would say that there is certainly a philosophical distance between Cronenberg and the clichés Olson has filled out the town with. The way Cronenberg directs the diner patrons, the ridiculous head bully at the high school (Kyle Schmid, giving a miserable performance, something that's a cross between a cartoon letter-jacket meathead and a cartoon '50s switchblade-wielding greaser, a performance bad enough that I'm at a loss to understand how Cronenberg, one of the great, underrated directors of actors, allowed it to happen), the small-town reporters, everybody basically who's not central to the action, announces loudly that he doesn't know these people. Not that he doesn't like them or respect them, but that their world is far enough away from his own that recreating it on film is, at least in this case, somewhat out of reach.

And judging from the script I guess it's out of Olson's reach, too. When the Stalls' young daughter wakes up screaming from a nightmare, is it necessary that first Tom, then Jack, then Edie, all have to come into her room and give her a cute little pep talk? Does everything have to be piled so high? And while storytelling wouldn't get very far as a form of communication without a few contrivances here and there, Olson's script is occasionally almost insulting. A small-town diner owner kills two small-time criminals in self defense, and the press goes nuts. He kills three big city gangsters in his front yard maybe a week later -- maybe a week -- and the press couldn't give a shit. And if all Carl Fogarty is there to do is to get Tom to come back to Philadelphia, why poke around for days on end? Why not say "I'll shoot your son if you don't get in the car." It comes to that anyway, more or less. If the only reason, and I suspect this is the case, is to allow doubt about whether or not Tom Stall actually is Joey Cusack to linger for a while, well, as noted earlier, I've got some bad news for you.

When he was doing press for the film, Cronenberg was repeatedly asked about the scene when Edie, after finding out beyond a doubt that her husband's real name is Joey Cusack, he's a killer, and the life he helped her build is a lie, slaps him, he grabs her, they struggle angrily together, and then both collapse on the stairs tearing at each other's clothes. After they've finished, Edie pulls her skirt down, looks at Tom with no less disgust than when she'd slapped him, and walks away. I remember Cronenberg responding to one question about this scene by saying "Sex and violence go together like bacon and eggs." He's made a career out of proving that this is essentially true, for him anyway, but you can get to attached to an idea, I'm starting to think. I think this scene is frankly absurd, it has nothing to do with Edie (and I should find the time to note that Bello is terrific in this film, her character one of the few who isn't a cliché, and she makes every moment work -- look at her response to the clerk in the shoe store, when she's looking for her daughter), or even Tom and his past. The scene is only about the fact that Cronenberg thinks sex and violence go together like bacon and eggs. And the scene is, unfortunately, central to the film, even though it doesn't work. There's no reason to believe that Edie finds sex with murderers a turn-on, but how else are we to take this? I know, power and things like this, human sexuality is complicated. That doesn't mean anything goes, everything will work, under every circumstance. The scene is as blatant an announcement of theme as Bello holding up a sign would have been.

This carries over in the other key relationship in the film, between Tom and his son Jack. Ashton Holmes' performance is as unfortunate as Kyle Schmid's, but going in sort of the opposite direction. He's the smart, sensitive nerd who's afraid to fight back, and Holmes plays him like he's auditioning to play one of Woody Allen's on-screen surrogates. Olson gives him a ton of precocious smart-ass lines, and they -- more than Holmes, to be fair -- verge on the unbearable, particularly when Tom has been unmasked as Joey and Jack wants to know if he tells his friend the truth about Tom, will Tom have him wacked. Or "If I rob Milliken's drug store will you have me grounded if I don't give you a piece of the action? What, Dad? You tell me." This latter, in particular, galls, both the writing and Holmes's delivery -- the delivery indicates that Holmes doesn't buy a word of what he's being made to say. "You can write this shit but you sure can't say it," Harrison Ford once said to someone or another. Holmes might have said it to Olson. What's he got to lose? Olson won't read his fucking script anyway. Anyhow, the whole relationship between Tom and Jack is nonsense, practically incoherent. Tom is a thoroughly loving father, and Jack seems to adore him. Tension sets in, at least for Jack, when Tom is celebrated for his bravery in the diner, while Jack can't even shove the bully who just shoved him. This is understandable, and potentially interesting, but all Olson and Cronenberg do with it is make Jack a snippy prick, one whose retorts, before and after the truth about his dad is revealed, but especially before, are meant to highlight some idea about violence but in context are total bullshit. When Jack finally blows his lid and punches the shit out of the bully, Tom says "In this family, we don't solve our problems by hitting people" and Jack says "No, in this family we shoot them!" Well, but...I can see the douchebag kid saying that, but what can it mean in the film? That Tom should have thought twice about killing those two criminals? I think the film is not saying that at all, actually, so why do I feel like this fuckin' kid is supposed to be audience surrogate?

It's maybe no surprise that the film's short, final stretch, which brings Tom/Joey to Philadelphia and a showdown with his brother, crime boss Richie Cusack (William Hurt), is my favorite section of the film. It takes everybody who has no business in a small town like that, not just Joey but also Cronenberg, and takes them back to their weird, slightly psychotic roots, exemplified by a totally off-the-wall performance by Hurt. This performance is a divisive one, and I can understand why, but I like it a great deal. Olson's writing of Richie is his own best work, Mortensen gets to play both sides of Joey/Tom at once, and he does so effortlessly, Cronenberg gets to stage some violence, Hurt goes bonkers...it's great. It's what the film really wants to be. The only crucial piece being left behind is Maria Bello's great performance, but these parts don't seem to fit together anyway. Despite what the film's last scene implies, this was a bad marriage.

As I hope I've made clear, none of this rests on the shoulders of Viggo Mortensen. It's simply that as far as I'm concerned, A History of Violence wasn't his equal. Two years later he would reteam with Cronenberg for a film that was more deserving of both of them. Eastern Promises wasn't as easily and quickly admired as A History of Violence had been, but the love for it has grown steadily over the years, probably because it's a much stranger, and therefore more interesting, film. Mortensen plays Nikolai, a low-level Russian gangster who chauffers mob boss, and restaurateur, Semyon (Armin Mueller-Stahl) and his son Kirill (Vincent Cassel) around London. At the beginning of the film, two seemingly separate events occur that will form the brutal, but interestingly low-key action to come: a young Russian woman dies during childbirth, and the nurse (Naomi Watts) caring for her takes on both her surviving baby and the diary she left behind as her personal responsibility. Meanwhile, in a Russian-run barbershop, Azim (Mina E. Mina) is cutting a man's hair when Azim's mentally handicapped son Ekrem (Josef Altin) walks in. Azim forces a straight razor into Ekrem's hand, and Ekrem then begins sawing into the throat of Azim's customer. This is something he promised his father he would do.

Where Nikolai is in all of this is part of what's interesting about Eastern Promises. He's just a driver at first, though when he's called on to dispose of the corpse of the man killed by Ekrem, Kirill -- who ordered the murder -- refers to Nikolai as "the undertaker." Along with this, when Anna, the nurse played by Watts, is led by evidence left by the dead girl to Semyon's restaurant, informing Semyon of the diary and the baby, though what this should mean to him she can't yet know, Nikolai is a threatening figure off to the side, more frightening because he's less obviously crazed than Kirill, frightening in his potential, as Semyon is, a similarity which will become crucial.

Eastern Promises is a film with a major twist, one I will have to spoil in due time, but before that, I have to say that the stark contrast between this and A History of Violence stems primarily from the fact that I think Eastern Promises is almost entirely successful. There are no bad performances (though as always, Cassel's flamboyance occasionally tests me), and some of the best work is being done off to the side of the main action -- Sinead Cusack as Anna's mother and The Shout director Jerzy Skolimowsky as her uncle Stepan, who translates the girl's diary and discovers the depths of her horrible connection to Semyon and Kirill, for example. Strongest are Mueller-Stahl, who I'm used to seeing play the magic grandpa with a twinkle in his eye and who is here perverting that very image, though thankfully without hammering on that idea -- Semyon is simply a man who knows how to project and use the image of a charming old man -- and Mortensen, who nails (I guess, I don't know, seemed good to me though) the Russian accent, first of all, but goes further by creating a unique, weirdly endearing, almost likably sinister presence. He seems to regard his job and those he works for with a sarcastic respect, a respect he nevertheless he kind of means. And he regards the wedge of moral questioning that Anna brings into his life (for the record, the part of Anna isn't rich with possibility, but Watts is reliably excellent) as...interesting. Worth considering, at any rate. But still terribly threatening -- the famous (relatively speaking) image of Nikolai threatening Stepan by thrusting two fingers into his own throat is wonderfully violent, and specific, even if the viewer isn't sure about that specificity. What weapon does that represent? A fork?

What really fascinates me about Eastern Promises, however, is how it all plays out, and where Nikolai ends up. First of all, this is certainly a violent film, that opening throat-cutting is one of the most brutally uncomfortably scenes I can think of, but it mostly kind of drifts along in a way that isn't digressive, but that shows a lack of interest in traditional crime film peaks and valleys. There is another throat-cutting (one less successful in that it seems more choreographed), and then, of course, the infamous climactic knife-fight in the sauna. Now, it's worth mentioning, by way of supporting my claim that Cronenberg and writer Steven Knight eschew the kinds of big moments we might expect, that even this scene, which involves a completely nude Mortensen fighting off two knife-wielding hitmen (I shit you not, when I saw this in the theater, a guy a couple rows in front of me got up to go to the bathroom about thirty seconds before this scene began, and came back maybe forty seconds after it ended. "What'd I miss?"), having his entirely vulnerable skin slashed at and having to actually get in closer if he has any hope of winning this, even in the case of this scene, we know who set up the attack but don't know what happens to him, and the two hitmen are not familiar to us. Oh, they may have been in the background here and there before, but Nikolai has no special grudge against either of them. Neither of them is The Man Who Killed My Wife. There is clear significance to the plot, but it's more significant as a fight, as violence.

In some ways, this sort of thing could be viewed as unsatisfying. It could be viewed that way even by me. Armin Mueller-Stahl plays a man as hateful as Chinatown's Noah Cross, and what happens to him? Well, we're told. Show don't tell guys, come on, don't you know anything about writing? Which, listen, I'd like to see more of Mueller-Stahl's fate than we do -- which is nothing, we see nothing -- but Cronenberg and Knight aren't making that movie. Eastern Promises is really pretty subversive in terms of how it handles its own material. The twist in the film, which is that Nikolai is actually an undercover cop, comes very late (and is revealed with little of the heightened drama such a moment would normally demand). As twists go, this one's not that interesting, and could be potentially disappointing if as a result Nikolai retroactively becomes a less intriguing character. Not so here, though, because a little bit later, when the film ends, the extent to which this has been Nikolai's film, and the depth of the character's mystery, becomes clear. What I'm talking about isn't a twist on a twist so much as it is the dawning realization that the twist, or the fact that we are now privy too, means very little in the grand scheme of things to one character in particular. And so what has really been upended by this twist? A talked-about sequel might have revealed that, but Cronenberg, for whatever reason, never made that film. I'd have seen it, eagerly, but I'm also glad it was abandoned. Knowing more about Nikolai could be a case of knowing too much.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)