Based on his work as a film director, I think it's safe to say that Bob Fosse's relationship to show business was somewhat complicated. The unspoken plot of at least his last three films (I'll cop right here to not having seen Sweet Charity, something I'm regretting right at the moment), and yes I think you could make a case for including Star 80 in this, is an escape from the old-fashioned and traditional to an adventurous new kind of entertainment. "Entertainment" being an important word, an inescapable one, whatever else Fosse's characters might be fleeing.

To narrow this down a little bit, look at Lenny, Fosse's 1974 film adaptation of Julian Barry's play about the life, trials, and death of comedian Lenny Bruce. Bruce began his career as a lame, sub-sub-sub-sub Henny Youngman Borscht Belt comic, bombing horribly until, in the film, a confluence of events and humiliations leads him to add some edge to his material. But surely what he's leaving behind with such palpable disdain is the same comedy that to some degree inspired him? This new path also leads more or less directly to his doom, in a couple of different ways.

So with that in mind, whatever influence Fosse drew from Fellini in making his 1979 autobiographical phantasmagoria All That Jazz, just now released by Criterion, it is also very much an expansion, almost a remake, of Lenny. The bad Catskills jokes show up here, too, when the film goes back to the childhood of choreographer, dancer, film director, and et cetera Joe Gideon, to the strip club where he tap dances between strippers, who molest and humiliate him before he takes the stage. As an adult, Gideon (Roy Scheider), obsessively ties together show business, performance, and sex. Maybe the hatred of old show business comes from that humiliation too. In any case, All That Jazz is basically this: Joe Gideon is working day and night on both a new stage musical, the specifics of which, outside of a couple of numbers, we're not privy to, and the editing of his new film, called The Stand-Up, about an aggressive and controversial stand-up comedian, played in All That Jazz by Cliff Gorman, who originated the role of Lenny Bruce in the original production of Julian Barry's play, though Dustin Hoffman took over for Fosse's film, all of which we should regard as a coincidence only, and about which we should make no more.

Anyway, add to that the facts that Gideon is a serial adulterer, having cheated on his previous wife Audrey (Leland Palmer), with whom he has a daughter (Erzsébet Földi), and who, Audrey is, starring in his new Broadway show, and currently cheating on his girlfriend Katie (Ann Reinking), also that he smokes too much, drinks too much, takes too many pills, and has a bad heart, all of which is suddenly intercut with scenes that don't seem to take place on our plane of existence, with Gideon talking about his life to a mysterious, ethereal woman (Jessica Lange), take all of that, as I say, and you have the plot, if that's the word you want to use.

All That Jazz has the reputation of being extremely critical examination of an artist's failings by the artist himself, and to some degree it certainly is. Gideon is mean, self-destructive, arrogant, unfaithful, all of that. But the film is also quite self-regarding -- Gideon is a genius, the women he blatantly cheats on still love him, and sometimes take a "Oh you men!" attitude towards him. It's very old-fashioned in that way, as the ever-pushing-forward Fosse could often be, which is part of the fascinating contradiction. The child tap-dancer grows up to furiously shed the old ways of dance and choreography, all the while hopelessly wrapped up in dying attitudes about actual life. Which, I mean...

So, too, was Lenny Bruce in Lenny, a film that All That Jazz resembles so closely, it was almost startling watching them back to back. When it comes to infidelity, the aspect of Bruce/Gideon/Fosse that Fosse is most willing to take his lumps for, Lenny is much harsher, and far less forgiving. Look at the scene when Lenny Bruce confronts his wife (Valerie Perrine) because she has fallen deeper into the life of sexual hedonism he essentially forced her into than he would like. His cruelty and hypocrisy is breathtaking, and Fosse doesn't flinch, or try to soften it. Yes, Bruce apologizes, but doesn't everybody? It's the moment itself, which Hoffman plays with admirable ice-bloodedness, that sticks. But that's there, and so is the connection with the world of burlesque (Bruce's wife was a dancer), shitty one-liner comedy (I don't want to be misunderstood, it's not one-liner comedy that I dislike, it's shitty one-liner comedy that I dislike) delivered in a maroon suit and bowtie. Joe Gideon/Fosse grew up in it, Bruce lived it. The child is father to the man, and Lenny is an earlier film than All That Jazz. You can almost chart Fosse's expansion on his ideas.

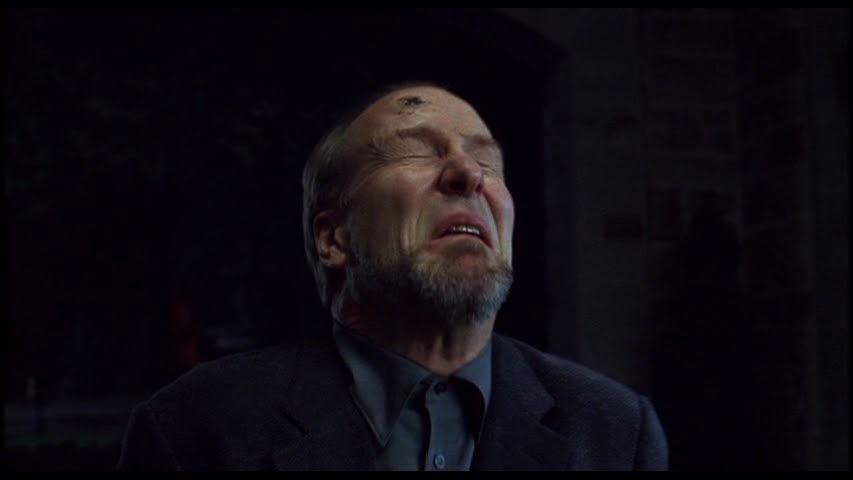

And have I even left myself enough room to address it all? Lenny ends, as biopics so often do, with the death of its subject. Lenny Bruce died of a drug overdose, after several arrests on obscenity charges, trials, possible jail time, and a stand-up act that had become a shambles. After a long look at one such depressing spectacle, Fosse and his editor Alan Heim abruptly cut to Bruce's corpse, nude on his bathroom floor. It's my understanding that there was originally supposed to be more of a build to that shot, but Fosse and Heim realized that all that footage was doing was prolonging the inevitable, so they cut to the corpse and ended the film. It's still a shocking cut, but within the only five films he directed, it's somehow not the greatest smash cut to a corpse in Bob Fosse's career.

Now, there's stuff in All That Jazz that I don't like. The film's big dance number, "Airotica," which Audrey says is the best work Gideon has ever done, strikes me as hopelessly silly, though as someone who knows nothing about dance or choreography my criticism of it should probably stop there -- suffice it to say, I much preferred the Reinking/Földir "Everything Old is New Again" number that comes later, which among other things is more relevant to the rest of the film in almost every way. Also, frequently comedy is an aim of All That Jazz, yet I don't find it particularly funny. It also indulges in one of my least favorite clichés, when, during a joyous montage of Gideon's wild antics after his bad heart lands him in the hospital, there's a shot of a bunch of his friends being just a bunch of total goofballs, cracking everybody up by putting rose petals on their face and making funny gestures. This is part of a terrible tradition that would take too long for me to unpack now, and anyway, it's just an example. Occasionally the movie falters, is what I'm getting at.

It doesn't matter, though, because Fosse's entire filmmaking career was building away from that stuff to something else. After the aforementioned antics, Gideon's health begins to slide, and the film is soon incorporating the basic style used in the Jessica Lange scenes to create what is both a real and unreal journey, by Gideon, into what might have been Hell had another filmmaker conceived of this (but what other filmmaker would, or could?) but in Fosse's hands becomes an explosive celebration of, mockery of, and metaphorical, melancholy, regretful, grateful embrace of death. The twisting of the Everly Brothers' "Bye Bye Love" into "Bye Bye Life," performed by Ben Vereen (and Roy Scheider, a bit -- neither a singer nor a dancer, Scheider, who is wonderful, as always, in the film, does a fine job of mimicking the necessary physicality), and the flamboyant dance number that surrounds it, is one of the more, let's say peculiar, depictions of the idea that when one dies, one's life flashes before one's eyes. It's vibrant, and moving, and ridiculous. It's insane that somebody had this idea and then was able to put it on screen. It's one of the most bracing confrontations with mortality I have ever seen. And if you're a far too morbid individual, as I am, one who dwells way too often on one's eventual and inevitable death, this scene is something of a gift.

Bob Fosse snatches up the death of Lenny Bruce and runs for it. And that final smash cut. Holy shit.

Tuesday, August 26, 2014

Sunday, August 24, 2014

The Cronenberg Series Part 14: He Is The Undertaker

This is sort of my way of saying that A History of Violence and Eastern Promises feel a little bit like an itch Cronenberg wanted to scratch, because even ten years later the influence of Pulp Fiction was in the air, and Cronenberg was aware of it, and intrigued. Plus, as non-genre writers like Richard Price who have taken very artistically profitable turns into the crime genre have noted, anything you might want to do creatively can be done within the structure of a crime story. Violence, as it happens, interests Cronenberg, as should probably be apparent now, and also in the air in 2005 was the changing nature of violence in action films. At the time of the release of A History of Violence, a new brand of brutal hand-to-hand combat choreography had been popularized by The Bourne Identity and The Bourne Supremacy; in those films, one person knows how to fight better than the other guy, and the fights don't last long. Though Cronenberg spoke somewhat dismissively of the Bourne films, their influence can be found in both A History of Violence and Eastern Promises. The main difference is than for Cronenberg, the acceptability of this kind of cinematic combat made some things easier for him, and unlike Doug Liman and Paul Greengrass, who'd directed the Bourne films, no one would expect Cronenberg to hold back, least of all himself. He wanted to deal with real violence -- which in truth he'd never really done before, the violence in his films prior to this being mostly fantastical in nature, in one way or another -- bluntly, and with his signature grotesqueness adapted to the crime scene.

What also happened was David Cronenberg found the actor who would be, and still could be, for him what, say, Robert DeNiro was for Martin Scorsese. Or, rather, what Leonardo DiCaprio currently is for Scorsese; that is, a very fine actor who happens to have the box office clout to help an aging but still extremely vibrant director get his films get made. Viggo Mortensen was pretty fresh off the Lord of the Rings trilogy, which made him a star. Mortensen, being who he is, cashed in by making three films in a row with David Cronenberg, a Western with director Ed Harris, a terribly bleak Cormac McCarthy adaptation, and so on. Mortensen hasn't been in the last two Cronenberg films (though he would have been in Maps to the Stars, Cronenberg's latest, however scheduling messed that up), but I hope they pair up again soon. Mortensen's ability to seem like both an ordinary man and an extraordinary one in the same film, even the same breath, his general, and genuine, strangeness, all were an immeasurable help in transitioning Cronenberg from the bizarre and the deranged into the relative realism of this pair of films. Although one of these could have used a little more help, which is I guess my way of finally getting started.

Based on a comic book by John Wagner and Vince Locke, with a screenplay by Josh Olson, A History of Violence is about a man named Tom Stall (Mortensen) who lives on a farm in rural Indiana with his wife Edie (Maria Bello), teenage son Jack (Ashton Holmes), and young daughter Sarah (Heidi Hayes). Tom owns a diner in town, and one night two ruthless criminals (Stephen McHattie and Greg Bryk, who we previously saw at the beginning of the film, leaving behind a pile of corpses, including a child, in a motel massacre) bulldoze into the diner. They're about to kill one of Tom's waitresses when something clicks in him and soon he's smashed one of them across the face with a coffee pot, scooped up a dropped gun, and pretty soon Tom, though wounded, has killed them both. His story hits the TV news, the evening papers, it's a story big enough to reach Philadelphia, where some gangsters get wind of it and think Tom Stall looks familiar. So Carl Fogarty (Ed Harris) and a couple henchman come to town, shadow Tom and call him "Joey," as in Joey Cusack, crazy violent Philly gangster who took out one of Fogarty's eyes with barbed wire. Is it possible that Tom Stall really is, or was, Joey Cusack? Of course it is, because otherwise the title A History of Violence would be meaningless. Maybe if it'd been called A History of Violence? some suspense could have been maintained on that count.

I suppose I should be blunt about this. Having seen A History of Violence several times over the last nine years, I have come to the conclusion that it's something of stumble, a film that is at once clumsy and lean, which makes for an odd mix though one that slightly recalls Cronenberg's earliest features. However, those films, like Shivers and Rabid, had the benefit of Cronenberg's immense and restless imagination. Even Spider, which he also didn't write, provided him with an expansive set of parameters. With A History of Violence, for the first time Cronenberg seems hemmed in by the ordinariness of it all -- said ordinariness includes the gangsters by the way.

Small town America does not rest easily alongside Cronenberg's aesthetic or philosophy. Josh Olson, I don't know about, and either way I'm grateful that the reaction to something Cronenberg is unfamiliar with is not to be condescending, patronizing, or insulting. The Indiana town where most of the film takes place is portrayed as regular, friendly, undramatic, save for that which would count as "every day" -- bullies and such. But Cronenberg is a filmmaker who turned down the opportunity to direct Witness because he felt no intellectual or philosophical connection to the Amish and therefore believed he would do a bad job. I would say that there is certainly a philosophical distance between Cronenberg and the clichés Olson has filled out the town with. The way Cronenberg directs the diner patrons, the ridiculous head bully at the high school (Kyle Schmid, giving a miserable performance, something that's a cross between a cartoon letter-jacket meathead and a cartoon '50s switchblade-wielding greaser, a performance bad enough that I'm at a loss to understand how Cronenberg, one of the great, underrated directors of actors, allowed it to happen), the small-town reporters, everybody basically who's not central to the action, announces loudly that he doesn't know these people. Not that he doesn't like them or respect them, but that their world is far enough away from his own that recreating it on film is, at least in this case, somewhat out of reach.

And judging from the script I guess it's out of Olson's reach, too. When the Stalls' young daughter wakes up screaming from a nightmare, is it necessary that first Tom, then Jack, then Edie, all have to come into her room and give her a cute little pep talk? Does everything have to be piled so high? And while storytelling wouldn't get very far as a form of communication without a few contrivances here and there, Olson's script is occasionally almost insulting. A small-town diner owner kills two small-time criminals in self defense, and the press goes nuts. He kills three big city gangsters in his front yard maybe a week later -- maybe a week -- and the press couldn't give a shit. And if all Carl Fogarty is there to do is to get Tom to come back to Philadelphia, why poke around for days on end? Why not say "I'll shoot your son if you don't get in the car." It comes to that anyway, more or less. If the only reason, and I suspect this is the case, is to allow doubt about whether or not Tom Stall actually is Joey Cusack to linger for a while, well, as noted earlier, I've got some bad news for you.

When he was doing press for the film, Cronenberg was repeatedly asked about the scene when Edie, after finding out beyond a doubt that her husband's real name is Joey Cusack, he's a killer, and the life he helped her build is a lie, slaps him, he grabs her, they struggle angrily together, and then both collapse on the stairs tearing at each other's clothes. After they've finished, Edie pulls her skirt down, looks at Tom with no less disgust than when she'd slapped him, and walks away. I remember Cronenberg responding to one question about this scene by saying "Sex and violence go together like bacon and eggs." He's made a career out of proving that this is essentially true, for him anyway, but you can get to attached to an idea, I'm starting to think. I think this scene is frankly absurd, it has nothing to do with Edie (and I should find the time to note that Bello is terrific in this film, her character one of the few who isn't a cliché, and she makes every moment work -- look at her response to the clerk in the shoe store, when she's looking for her daughter), or even Tom and his past. The scene is only about the fact that Cronenberg thinks sex and violence go together like bacon and eggs. And the scene is, unfortunately, central to the film, even though it doesn't work. There's no reason to believe that Edie finds sex with murderers a turn-on, but how else are we to take this? I know, power and things like this, human sexuality is complicated. That doesn't mean anything goes, everything will work, under every circumstance. The scene is as blatant an announcement of theme as Bello holding up a sign would have been.

This carries over in the other key relationship in the film, between Tom and his son Jack. Ashton Holmes' performance is as unfortunate as Kyle Schmid's, but going in sort of the opposite direction. He's the smart, sensitive nerd who's afraid to fight back, and Holmes plays him like he's auditioning to play one of Woody Allen's on-screen surrogates. Olson gives him a ton of precocious smart-ass lines, and they -- more than Holmes, to be fair -- verge on the unbearable, particularly when Tom has been unmasked as Joey and Jack wants to know if he tells his friend the truth about Tom, will Tom have him wacked. Or "If I rob Milliken's drug store will you have me grounded if I don't give you a piece of the action? What, Dad? You tell me." This latter, in particular, galls, both the writing and Holmes's delivery -- the delivery indicates that Holmes doesn't buy a word of what he's being made to say. "You can write this shit but you sure can't say it," Harrison Ford once said to someone or another. Holmes might have said it to Olson. What's he got to lose? Olson won't read his fucking script anyway. Anyhow, the whole relationship between Tom and Jack is nonsense, practically incoherent. Tom is a thoroughly loving father, and Jack seems to adore him. Tension sets in, at least for Jack, when Tom is celebrated for his bravery in the diner, while Jack can't even shove the bully who just shoved him. This is understandable, and potentially interesting, but all Olson and Cronenberg do with it is make Jack a snippy prick, one whose retorts, before and after the truth about his dad is revealed, but especially before, are meant to highlight some idea about violence but in context are total bullshit. When Jack finally blows his lid and punches the shit out of the bully, Tom says "In this family, we don't solve our problems by hitting people" and Jack says "No, in this family we shoot them!" Well, but...I can see the douchebag kid saying that, but what can it mean in the film? That Tom should have thought twice about killing those two criminals? I think the film is not saying that at all, actually, so why do I feel like this fuckin' kid is supposed to be audience surrogate?

It's maybe no surprise that the film's short, final stretch, which brings Tom/Joey to Philadelphia and a showdown with his brother, crime boss Richie Cusack (William Hurt), is my favorite section of the film. It takes everybody who has no business in a small town like that, not just Joey but also Cronenberg, and takes them back to their weird, slightly psychotic roots, exemplified by a totally off-the-wall performance by Hurt. This performance is a divisive one, and I can understand why, but I like it a great deal. Olson's writing of Richie is his own best work, Mortensen gets to play both sides of Joey/Tom at once, and he does so effortlessly, Cronenberg gets to stage some violence, Hurt goes bonkers...it's great. It's what the film really wants to be. The only crucial piece being left behind is Maria Bello's great performance, but these parts don't seem to fit together anyway. Despite what the film's last scene implies, this was a bad marriage.

As I hope I've made clear, none of this rests on the shoulders of Viggo Mortensen. It's simply that as far as I'm concerned, A History of Violence wasn't his equal. Two years later he would reteam with Cronenberg for a film that was more deserving of both of them. Eastern Promises wasn't as easily and quickly admired as A History of Violence had been, but the love for it has grown steadily over the years, probably because it's a much stranger, and therefore more interesting, film. Mortensen plays Nikolai, a low-level Russian gangster who chauffers mob boss, and restaurateur, Semyon (Armin Mueller-Stahl) and his son Kirill (Vincent Cassel) around London. At the beginning of the film, two seemingly separate events occur that will form the brutal, but interestingly low-key action to come: a young Russian woman dies during childbirth, and the nurse (Naomi Watts) caring for her takes on both her surviving baby and the diary she left behind as her personal responsibility. Meanwhile, in a Russian-run barbershop, Azim (Mina E. Mina) is cutting a man's hair when Azim's mentally handicapped son Ekrem (Josef Altin) walks in. Azim forces a straight razor into Ekrem's hand, and Ekrem then begins sawing into the throat of Azim's customer. This is something he promised his father he would do.

Where Nikolai is in all of this is part of what's interesting about Eastern Promises. He's just a driver at first, though when he's called on to dispose of the corpse of the man killed by Ekrem, Kirill -- who ordered the murder -- refers to Nikolai as "the undertaker." Along with this, when Anna, the nurse played by Watts, is led by evidence left by the dead girl to Semyon's restaurant, informing Semyon of the diary and the baby, though what this should mean to him she can't yet know, Nikolai is a threatening figure off to the side, more frightening because he's less obviously crazed than Kirill, frightening in his potential, as Semyon is, a similarity which will become crucial.

Eastern Promises is a film with a major twist, one I will have to spoil in due time, but before that, I have to say that the stark contrast between this and A History of Violence stems primarily from the fact that I think Eastern Promises is almost entirely successful. There are no bad performances (though as always, Cassel's flamboyance occasionally tests me), and some of the best work is being done off to the side of the main action -- Sinead Cusack as Anna's mother and The Shout director Jerzy Skolimowsky as her uncle Stepan, who translates the girl's diary and discovers the depths of her horrible connection to Semyon and Kirill, for example. Strongest are Mueller-Stahl, who I'm used to seeing play the magic grandpa with a twinkle in his eye and who is here perverting that very image, though thankfully without hammering on that idea -- Semyon is simply a man who knows how to project and use the image of a charming old man -- and Mortensen, who nails (I guess, I don't know, seemed good to me though) the Russian accent, first of all, but goes further by creating a unique, weirdly endearing, almost likably sinister presence. He seems to regard his job and those he works for with a sarcastic respect, a respect he nevertheless he kind of means. And he regards the wedge of moral questioning that Anna brings into his life (for the record, the part of Anna isn't rich with possibility, but Watts is reliably excellent) as...interesting. Worth considering, at any rate. But still terribly threatening -- the famous (relatively speaking) image of Nikolai threatening Stepan by thrusting two fingers into his own throat is wonderfully violent, and specific, even if the viewer isn't sure about that specificity. What weapon does that represent? A fork?

What really fascinates me about Eastern Promises, however, is how it all plays out, and where Nikolai ends up. First of all, this is certainly a violent film, that opening throat-cutting is one of the most brutally uncomfortably scenes I can think of, but it mostly kind of drifts along in a way that isn't digressive, but that shows a lack of interest in traditional crime film peaks and valleys. There is another throat-cutting (one less successful in that it seems more choreographed), and then, of course, the infamous climactic knife-fight in the sauna. Now, it's worth mentioning, by way of supporting my claim that Cronenberg and writer Steven Knight eschew the kinds of big moments we might expect, that even this scene, which involves a completely nude Mortensen fighting off two knife-wielding hitmen (I shit you not, when I saw this in the theater, a guy a couple rows in front of me got up to go to the bathroom about thirty seconds before this scene began, and came back maybe forty seconds after it ended. "What'd I miss?"), having his entirely vulnerable skin slashed at and having to actually get in closer if he has any hope of winning this, even in the case of this scene, we know who set up the attack but don't know what happens to him, and the two hitmen are not familiar to us. Oh, they may have been in the background here and there before, but Nikolai has no special grudge against either of them. Neither of them is The Man Who Killed My Wife. There is clear significance to the plot, but it's more significant as a fight, as violence.

In some ways, this sort of thing could be viewed as unsatisfying. It could be viewed that way even by me. Armin Mueller-Stahl plays a man as hateful as Chinatown's Noah Cross, and what happens to him? Well, we're told. Show don't tell guys, come on, don't you know anything about writing? Which, listen, I'd like to see more of Mueller-Stahl's fate than we do -- which is nothing, we see nothing -- but Cronenberg and Knight aren't making that movie. Eastern Promises is really pretty subversive in terms of how it handles its own material. The twist in the film, which is that Nikolai is actually an undercover cop, comes very late (and is revealed with little of the heightened drama such a moment would normally demand). As twists go, this one's not that interesting, and could be potentially disappointing if as a result Nikolai retroactively becomes a less intriguing character. Not so here, though, because a little bit later, when the film ends, the extent to which this has been Nikolai's film, and the depth of the character's mystery, becomes clear. What I'm talking about isn't a twist on a twist so much as it is the dawning realization that the twist, or the fact that we are now privy too, means very little in the grand scheme of things to one character in particular. And so what has really been upended by this twist? A talked-about sequel might have revealed that, but Cronenberg, for whatever reason, never made that film. I'd have seen it, eagerly, but I'm also glad it was abandoned. Knowing more about Nikolai could be a case of knowing too much.

Tuesday, August 12, 2014

It's Over

Maurice Pialat was 43 when he made L'Enfance Nue, his first feature film, and was comfortably into middle age when he made his second, We Won't Grow Old Together. This latter film, which Kino Lorber is releasing on DVD and Blu-ray today, is plainly not the work of a young man. It's the story of a diseased love affair between a man in his 40s named Jean (Jean Yanne) and a woman in her 20s named Catherine (Marlene Jobert) that struggles and collapses and rebuilds itself again and again, over the course of six years. It's one of the most profoundly uncomfortable viewing experiences I've had in some time, and it left me uncertain what to think. There's unmistakable evidence of artistic success in that reaction, but no comfort.

The film opens with the couple in bed, Jean barely awake while Catherine wonders idly, though not insignificantly, about their past together, and their present. It moves on to their morning, and removed from the ambiguity of that opening scene you can see their ease together, and their humor as Jean asks if Catherine wants bread and butter while she dries her hair. A few scenes later, Catherine is helping Jean in his work -- he makes documentary films, and while shooting on a busy street, he with the camera, she working the sound, he berates her for failing to keep up, finally sending her away. He breaks up with her, in fact, sends her to the train station. But she doesn't board and he comes to get her. They smile wryly at each other, and the fight is in the past. The next time Jean bullies her, they're in his car, and it's sudden: he wonders when she'll get a job, then asks if she'll get another office job, then asks why she won't aim higher, then calls her useless, stupid, ugly. She sits and listens, and the look on Jobert's face is heart-stopping. Every word is a slap but her face and posture show that she's terrified that soon the slaps will become real if she protests, or fires back.

They break up again, for a little while.

When they get back together, there are physical slaps, and in fact before this there was reason to believe Jean had already been hitting Catherine. But now we see it, and there's one terrifying moment of violence that could at any point cross over into rape. In truth, there's no denying that Jean had been hitting her before we actually see it. Her face in the car almost proves it. I won't make too much of this, or get into it too deeply, but my previous job occasionally involved me being trained in matters of domestic violence prevention and aftermath (for the record, my involvement in this arena was very far from extensive), and in one of those training sessions we saw a video that a husband had told one of his sons to take of him, the husband, verbally abusing his wife, the boy's mother. The physical abuse in this case (recorded, but not part of what I saw) was extreme, and in the video of the verbal abuse, the woman's face is very much like Catherine's in the car: weathering the storm, hoping it will pass without becoming physical, blank-faced but terror-stricken, silent, motionless.*

For the first half of We Won't Grow Old Together, this is essentially the relationship we see. A point is reached when Catherine becomes more firm, and Jean begins to regret his behavior. "As they always do," you might say, and, yes, indeed, though to the degree that it matters sometimes that regret makes a difference. In the essay about the film included in with the Kino disc, Nick Pinkerton makes it clear that this was a very autobiographical film for Pialat, and that he'd once had a similarly tempestuous relationship with a younger woman. It matches up in obvious ways, too: Pialat started out making documentaries, like Jean, and Jean's age would have matched Pialat's a few years before he broke into features.

It's not my place, and I'm in no way qualified, to look at this film and use it to condemn Pialat, and I'm not going to do that, but I often see We Won't Grow Old Together as a "breakup" movie, or a "relationship" movie, when it's quite clear to me that it's a film about abuse. It's just that it's one where the abuse reaches a point beyond which the abuser won't allow himself to go. Usually in films, the abuse goes all the way, while this form, which remains inexcusable, must be more common. In any case, Pialat is not excusing himself. I don't know how exactly Jean's behavior reproduces Pialat's own, but Pialat, Pinkerton notes, claimed this film was quite factual. And I think the film hates Jean. I won't stretch that to mean Pialat hated himself, but there's a palpable reaction of pure disgust to some of the things Jean does in this film. Jean Yanne, like Marlene Probert, is exceptionally good in this, which means, by my reckoning, he, the other Jean, the film Jean, is exceptionally hateful.

When the film begins to soften up, and Jean, the film Jean, begins to change, my impulse is to pull back from the film and say "Well fuck you all the same." But Pialat isn't saying "You see, he's not so terrible after all." To the degree he's saying anything, he's saying "This is what happened." That's the sort of film that an audience really has to deal with. They won't grow old together, and thank Christ.

*For the record, the case to which I'm referring ended well: the wife tricked her husband (I can't quite remember the details) into incriminating himself, and walking into the arms of the police. With so much abuse caught on camera, there was no case for the defense, and this particular piece of shit was given something like thirty years in prison, which is currently the stiffest sentence ever given in a domestic violence case.

Sunday, August 10, 2014

The Cronenberg Series Part 13: Under the Fountains and Under the Graves

[Spoilers for both eXistenZ and Spider are contained herein]

The turn of the century, or right around there, can now be looked back upon as a pretty significant turning point in David Cronenberg's career. This change began in the late 1980s, really, when his body horror films began to merge with a more overtly literary, for lack of a better word, and which I use here both literally and figuratively, sensibility. This sensibility had always been present, but Cronenberg's fierce intellectualism, pairing off with an almost supernatural ease with classic genre structures as it does, stopped being subtext by the time of Dead Ringers in 1988, and by Naked Lunch in 1991 his grotesque images were lifted out of genre and placed in the arthouse. Though there wasn't in fact much difference for anyone paying attention, spending most of the 1990s adapting William S. Burroughs, David Henry Hwang, and J. G. Ballard had changed the way Cronenberg was perceived. He'd officially become "interesting." Never before had he made a film as extreme as Crash in 1996, but while it faced protests and calls for censorship, it also put him in competition at Cannes for the first time in his career.

If the above sounds cynical, I don't mean it to be, at least the cynicism is not directed at Cronenberg. The artistic impulse that led to The Brood was no less pure than the one that led him to make Naked Lunch, but, in ways outside of his control, having a literary base seems to have helped his career. All if which makes Cronenberg's 1999 film eXistenZ, whatever its links to his famous early work, feel almost like an anomaly, somehow out of character. In an interview with Serge Grunberg, later collected as part of David Cronenberg: Interviews with Serge Grunberg, Cronenberg talked about his relationship with his earlier films:

...With my new movie, eXistenZ, people say it reminds them somewhat of Videodrome. I can see that in a superficial way. I'm wondering though, I think I'm not the same person who made those movies, and when I watch the movies that I've made it's shocking really. I mean it's shocking because it's not a question of not remembering what I did...but I'm surprised at what I've done. It seems alien to me. I find it very difficult. Almost impossible to watch my old movies. I never do. I've recently had to do the commentary on laser disc, and now DVD versions of the film...And even Crash, watching it a year later and talking about it, it's almost as though I'm talking about somebody else's movie. It's very strange. So I do feel that distance, it's increasing rapidly as I get older.

The first thing to say about eXistenZ, it seems to me, and this is a key point, is that to date it is the last original script written by David Cronenberg to make it to the screen. A little while later it was announced that Painkillers, another original script, would be filmed, but that never happened, and I remember some time in the mid 2000s, when asked about the status on Painkillers, Cronenberg said it wasn't happening, and that he was no longer interested in doing it anyway. This is the sort of accumulation of ambivalence that generally indicates that the film in question -- in this case eXistenZ -- is no good, or a somewhat tedious final trip to the well. However, eXistenZ is a strong shot of the old Cronenberg, the genre Cronenberg, a return in some ways to Videodrome, as mentioned, while also being the first part of a two-film mucking-around with twist ending and the nature of reality, a structure and theme that were hugely popular in mainstream filmmaking at the time. However the other film, 2002's Spider, based on Patrick McGrath's novel and with a script by McGrath, though it feels more at one with the stately perversion of Crash and Dead Ringers, it's another step in Cronenberg's pulling away from the grotesque, even cutting disturbing images from the novel that McGrath had included in the script with the full confidence that Cronenberg was the man to bring them off. But he didn't do them at all. Everything was changing. So you see these two films match up quite well, and I'm not just being lazy.

The injured Geller is hustled out of there by Pikul because it appears that this may not have just been a case of a lone gunman, but rather they may (or may not) be caught up in some kind of anti-gaming terrorist attack. They hit the country roads at night, get a motel room, and because Geller has this new game of hers loaded into her game controller, which she treats and cares for as if it was a living thing which it kind of is, or actually is, and part of taking care of it is to play it, she needs Pikul to get a bioport. I'll skip ahead -- he does, but the black market bioport is intentionally compromised by the terrorist plot, which draws into the drama the very Cronenbergianly named Kiri Vinokur (Ian Holm), a kind of mob doctor for game controllers. His allegiance will be questioned, and the health of Geller's controller is a constant concern. For her, anyway.

But anyway. So. Enough of this plot shit...which is a sentiment not entirely irrelevant to eXistenZ. Of course Pikul and Geller do begin playing the game, and to Pikul it's a marvel: so like the real world that eventually the question of eXistenZ (which, I mean...) becomes what is real and what is the game. By the end of the film the divide is still unclear -- also unclear who is the terrorist and who is the terrorized -- and virtual reality videogames seem to have just come in for a right skewering. But back to my point: the plot of "eXistenZ" (this being sort of distinct from eXistenZ, you understand) is very complicated and full of double crosses, and is not treated very seriously, except to the extent that it, and its dangers, bleed over into reality (or "reality," but, I mean, you get that by now), and Pikul and Geller react to a lot of it as most people would react to any game that called for role-playing, that is to say, with a kind of self-conscious enthusiasm. And so much of eXistenZ plays like an almost romantic light thriller. It's sort of like North by Northwest, and if in that film Hitchcock used a train entering a tunnel as a visual wink towards wedding night copulation, Cronenberg uses the insertion of a kind of living, fleshy plug into a bioport in one's spine as a wink towards I think in this case anal sex. With Jennifer Jason Leigh performing anal sex upon Jude Law. Anyhow, I'm being diverted again.

So eXistenZ is ostensibly about virtual reality video games, but the points made within it, about the addictive quality of fantasy, and the formal aspects of artistically constructed fantasy, have more to do, particularly in 1999, with film than with video games. Or at least Cronenberg recognized that, as one would have then extrapolated on the idea of virtual reality games as a science fiction concept, all or anyway many of the things one might wind up thinking about were already present in cinema. So when Geller regrets that a video game character she and Pikul have just interacted with spouts boring dialogue and is not especially well-formed, these seem less like something that a late-90s game designer would be especially worried about, but a commercial filmmaker would be. The groundwork was being laid, but of course much of the evolution process of video games has been to mimic films as much as possible (I understand there are exceptions, but I'd say this is still pretty much true). To really immerse a player in a game is to make that game more like a film. And at one point in eXistenZ, Pikul, who is being swept along in the game, and is rolling with it all as well as he can, is briefly jarred by the fact that one moment he's making love to Geller in a stockroom (Cronenberg is quite capable of including metaphors for a thing and the thing itself in one film, even one scene), and the next instant he's in a kind of fish-gutting factory. Yes, these kinds of transitions existed in video games, but what Pikul is reacting to is a cut, and what he's very specifically reacting to is Cronenberg's cut, his cinematic cut -- the editing of Ronald Sanders on the David Cronenberg film eXistenZ.

Cronenberg at this point in his career and his life is perhaps a bit tired with what he'd been doing, or rather, what he was known for, and while his work after eXistenZ is actually more classical in many ways than his earlier films, in eXistenZ he's almost mocking classic filmmaking. Or sending it up, maybe. As suggested earlier, this film now plays to me as almost a straight comedy, and though it's a pretty gory one it's also not actually mean. That is to say, he's not trying to plunge a knife in the heart of movies, but you can't send up the conventions, or possible future conventions, of virtual reality without acknowledging that movies are susceptible to the same dings. If video games can be addictive, as the AA atmosphere of the bookending presentation scenes imply, as a substitute for reality, if you can lose yourself within the life you pretend to be living as you play, and if you're starting to feel actual heart-beating emotions connected to these unreal events and people (and the terrorist motives in the film, and the plot of the game, revolve around this danger), then what counts as real and what doesn't becomes a question rather than a statement. And if you can be lost in the fantasy of video games, why not the more proven comfort and potentially (depending) passive fantasy of film?

While Cronenberg downplays the similarities between eXistenZ and Videodrome they're less superficial than he claims. In the case of the earlier film, see video and cable television for video games (within the context of the individual films these ideas themselves become very superficial, I'll grant you, and Cronenberg). Unlike Videodrome, though, eXistenZ almost feels conventional, at least in 1999, and now. It wouldn't have been had he made it back when he made Videodrome, but the narrative structure, and the hazy reality and twisty nature of the plot in 1999 becomes part of the game, and part of the joke. Though the "what exactly is going on?" punchline here does have a chill to it.

eXistenZ is often mentioned in relation to other science fiction films of the era that question the nature of reality, such as Alex Proyas's Dark City and the Wachowskis' The Matrix, but you could also connect it to the flood of "twist ending" films that soaked the era. The nature of twists such as the one that made M. Night Shyamalan's The Sixth Sense so famous is that it forces the audience to question what they've already seen, or the "reality" of the film. It's only later in eXistenZ that the audience questions the fact that the bizarre meat gun Jude Law assembles in the Chinese restaurant late in the film was the same gun, or same kind of gun, used by the terrorist in the film's opening scene. This realization makes you wonder if anything was real. The film doesn't have a twist, as such, but the whole premise almost functions in the same way. And traditionally that's how Cronenberg achieved this effect, not by pulling the rug out from under the viewer but by never giving them a rug in the first place. Yet in 2002 he did make his version of the twist ending thriller with an adaptation of Patrick McGrath's Spider.

Spider has a twist ending, but it also forces the audience to question their surroundings almost right from the beginning, because it's told from the point of view of a schizophrenic named Dennis Cleg, nicknamed Spider (Ralph Fiennes) who as the film begins has just been released from a mental asylum. We first see him getting off a train, and the time is clearly modern day, the other passengers wearing contemporary clothes and so on, but that's the last time Spider will feel contemporary. The boarding house to which Spider has been referred, a boarding house run by the stern Mrs. Wilkinson (Lynne Redgrave), is basically our only present day setting, the rest of the film involving flashbacks to Spider's childhood, and Mrs. Wilkinson pretty clearly doesn't have much interest in keeping the place up to date; her clientele consists entirely of men like Spider. So that's our first bit of wonkiness: when are we? Even though we know, everything feels off. It's both 2002 and the early 1960s at the absolute latest.

The question otherwise becomes, what happened to Spider to make him this way? Or what did he do? Spider is who we follow, but he's a shambling, mumbling, wreck of a human. It's not that he's inarticulate, it's that the viewer can't tell if he is or not. McGrath's novel is written in the first person, and Spider is quite articulate indeed. The novel begins:

I've always found it odd that I can recall incidents from my boyhood with clarity and precision, and yet events that happened yesterday are blurred, and I have no confidence in my ability to remember them accurately at all.

Which sets things up nicely, but anyhow, that's not the Spider of the film. Or maybe it is, in his head, but Fiennes plays him as a man who is constantly talking to himself but specific words can only be understood very sporadically. His fingers are perpetually tobacco-stained, his hair is stuck in a kind of Samuel Beckett-like dishevelment, he's hunched, he acts fearful of other people, and he's always scribbling in his...journal? It's a notebook of some sort, and what he's writing isn't English. Is it an intentional code? Or is it what Spider has come to believe is language? In any case, we're not getting any information from him, and as such Fiennes' performance is something of a tour de force, a silent film performance if silent film actors were instructed to be as still as possible. What we learn about his past, and why he ended up in a mental institution, comes from his flashbacks. Spider, by which I mean Fiennes, is present in these flashbacks (shades of Johnny Smith being present in his visions in The Dead Zone), as he follows his younger self (Bradley Hall) home where he lives in fear of his love for his mother (Miranda Richardson) and resentful of his father (Gabriel Byrne), who he views as a drunk philanderer, and finally murderer of his mother. When she's dead, Spider's father brings in Yvonne (Richardson again), the kind of woman who would once have been called a slattern. Boozy, coarse, generally inappropriate, she's reminiscent of a woman young Spider saw when, in the time before his mother's death, he went to retrieve his father from the local pub. This blonde woman -- blonde and coarse and Cockney in the way Yvonne is -- flashed the boy, frightening him and unhooking something in his pending, or occurring, puberty, as well, possibly, in the madness that is, let's not forget, a problem of biochemistry, not simply a matter of seeing the wrong thing at the wrong time.

So, again, enough of this plot shit. When Miranda Richardson shows up twice, once as Spider's pure angel of a mother and twice as, and let's not put too fine a point on this, her whorish replacement (and accomplice in her murder, by the way), Spider's madness begins to take shape, and the extent to which we can trust his memory becomes a matter for debate. Gabriel Byrne told Cronenberg that the role of Bill Cleg was the hardest one he'd ever had to play, because in every scene he had to play Bill in a way that kept a baseline of the individual character while adding different distortions, or reality as the case may be, based on the facts, or "facts" (as the case may be), Cronenberg wanted to communicate. Meanwhile Miranda Richardson -- who Cronenberg seems to have cast because he's always wanted to see her really cut loose, and boy does she (this is a compliment) -- has to play Mrs. Cleg, Yvonne, and eventually, as Spider's past begins to take over his present, Mrs. Wilkinson, and finally Yvonne as Mrs. Wilkinson. And is Yvonne even a person?

This is the key. Spider has been driven mad, or hastened to madness, by the murder, with a shovel, of his mother by his father, because his drunken father wanted Yvonne. But Yvonne is just "Yvonne," the nameless woman who flashed him, and whose sexuality he associates with his mother -- perhaps because she's the only woman he knows? -- and the shame of the accompanying arousal forces him to imagine her dead, and the busty Yvonne to storm through, both satisfying his lust, in the sense that he can ogle her without guilt, and inciting his rage because she's taken the place of his sainted mother. But she's his mother, his father didn't kill his mother (when Bill Cleg is off fornicating with "Yvonne," does the audience at that point question how Spider could be privy to these scenes?), his father is evidently as good a man as his mother was a good woman, so that when Spider exacts his revenge, it's not Yvonne he kills. But in the end, his mother has been murdered.

That's our twist, that's how Cronenberg, and McGrath of course, has upended everything, and forced the audience to rewind the film in their brains. The difference here is that Spider is finally a mix -- not consciously, but still -- of the relentless irreality of eXistenZ and the twist structure of The Sixth Sense, so that if while watching Spider you don't know what the ending will be, you do know that what you're being told can't be right. This may be why the twist doesn't infuriate the way some twists can, when your investment in what you've seen is blown apart for the love of a gimmick, because you're unable to invest in the plot because you don't quite know what the plot is. But it's possible to be invested in Spider, and in fact I'd argue that Spider is Cronenberg's most emotionally powerful film since The Fly. To make another comparison, Spider is closer to Scorsese's Shutter Island, a tremendously good film I happened to rewatch recently, than other twist films because in both cases the twist renders what has come before, in relation to the respective protagonists, not irrelevant, which is the danger, but actually sadder. The fact that Spider isn't a victim doesn't make him hateful -- it means he has no hope.

As I said before, McGrath's novel has Cronenbergian grotesque imagery -- a bleeding potato, a tiny dead fetus in a bottle of milk -- that Cronenberg skipped over. With eXistenZ behind him, which is wild to the point of satire, with its tooth-shooting meat guns and living-flesh game controllers that buttfuck your spine, it's not impossible to understand that Cronenberg recognized that something was now past. It's also telling, if I may briefly jump ahead, that he cut a dream sequence from his next film that involved a man taking a gun out of his own chest wound because Cronenbreg realized he was repeating himself (it's also telling that for Cronenberg, that is repeating himself). Though the next phase of his career doesn't involve any narrative experimentation, this one-two shot of eXistenZ and Spider, films that traffic in story conventions of their very specific time, seems to have cleansed him of a certain self-consciousness that may have been creeping in, the kind of self-consciousness that hits a person when they've decided it's time to move on, but they haven't done it yet, because they have this one last thing to do.

Monday, August 4, 2014

A Trysting House for Noisy Couples

James Kennaway was the author of seven novels, but only five were published during his short lifetime. The first of those, Tunes of Glory, is perhaps his most famous, and even in that case the fame now reflects more on the Ronald Neame film version, starring Alec Guinness. One of his posthumous novels has maybe the greatest title ever given to a story about someone discovering that their bad habits have drastically shortened their life -- it's called The Cost of Living Like This. In that book (which I haven't read, but will, and soon) the lead character is dying of lung cancer at the age of 38, and one might pair this with one's knowledge that Kennaway himself died at 40 and think "Ah, I see," but no, Kennaway died when he suffered a heart attack while driving. This was forty-five years ago now. Since then, people will occasionally watch one of the films Kennaway wrote, such as The Battle of Britain and The Shoes of the Fisherman, as well as Tunes of Glory, the screenplay for which he was responsible for. The novel Tunes of Glory has sporadically regained some kind of grip on a life in print (the most recent edition I've been able to find naturally has a picture of Alec Guinness from the film on the cover), while his other novels, which also include Some Gorgeous Accident, a fictionalized account of the affair Kennaway's wife had with John Le Carré, have mostly slid from view.Until now, or until recently. Valancourt Books, a terrific publisher that focuses on forgotten or neglected literary, horror, Gothic, and gay fiction. Last month, Valancourt put out a new edition of The Cost of Living Like This, and tomorrow they'll reprint Kennaway's 1963 novel The Mind Benders. The Mind Benders was also adapted into a film, again with a screenplay by Kennaway, this time directed by Basil Dearden, and starring Dirk Bogarde. And listen, I'll have to cop to this eventually, my experience of Kennaway, apart from a distant viewing of The Battle of Britain, is confined to a recent reading of this very book, which is to say, The Mind Benders. But as often happens when the judgment of history has been found wanting, and a writer like Kennaway is rescued from the void, my reaction, even to an imperfect book like The Mind Benders, is one of excitement, as though Kennaway was a talented newcomer, not someone whose entire life's work has already been produced, and whose death occurred almost fifty years ago.

The novel begins by introducing the reader to Major Hall, an officer in British Intelligence, nicknamed "Ramrod" because of his very narrow and rigid approach to his work. Kennaway's first sentence tells us that Ramrod is "hardly as exciting as his celebrated colleague...James Bond," which when reflected upon once you're deeper into the book is a knock on both Ramrod Hall and James Bond. Bond is a ridiculous fiction whereas Ramrod, Kennaway argues with that very precise type of sardonicism perfected by mid-century English writers, is what such men are really like. I'm always skeptical when such an argument is made in a work of fiction, but that doesn't mean Kennaway's way of going about it isn't delightful. Later in the novel, after Ramrod has watched a strange film that is central to the novel's plot and Ramrod's own investigation, Kennaway writes:

The film puzzled more than impressed him, which was not perhaps too surprising, as the only thing that really impressed him were pantomimes on ice and actors flying in Peter Pan. 'Damn clever,' he'd say of them, or sometimes, 'Damnably clever.'

To clarify things, Ramrod is investigating a Nobel Prize-winning scientist named Sharpey, whose Communist past and current strange behavior have put him under suspicion of espionage. When Sharpey leaps to his death from a moving train -- as his naïve young colleague Jack Tate watches in horror -- Ramrod is led to investigate Sharpey's actual work, which has to do with sensory deprivation. At the college where Sharpey and Tate work is a lab where Sharpey and another colleague, an American expatriate named Longman, have built a tank and suit and overall environment that allows them to reproduce the basic conditions suffered by a French scientist named Bonvoubois, who was found stumbling frightened and half-mad from a natural, Arctic form of sensory deprivation. It's not the cold that affected him, and, subsequently, student volunteers, so strongly, Sharpey and Longman realized. The film Ramrod watches, with Tate and Norman, Sharpey and Longman's lab assistant, shows the two scientists, one dead and one not yet met by Ramrod (or the reader), explaining themselves:

'It hadn't anything to do with low temperature,' [Sharpey explains on the film]... 'Bonvoubois and our student guinea pigs had been affected not by the cold but by their prolonged isolation. One week later we changed the name of the laboratory outside our main building to "Isolation".'

With Tate not being smart enough and Norman merely being an assistant, that leaves Ramrod with Longman. Longman, it turns out, is the protagonist of The Mind Benders, though he doesn't appear in person, as it were, until page 42 if this 145-page novel. Longman is married to Oonagh, whom Jack Tate is in love with, and he, Longman, has been missing from the lab for several weeks. Sharpey died, Kennaway tells us, and Longman fled. When he goes to Longman's home to question him, Ramrod (and Tate, who, to put it bluntly, finds excuses to come sniffing around) finds a calm man who is deeply in love with his wife, with a kind of weary, or even melancholy, uxoriousness, and this love is reciprocated. But when he learns of Sharpey's death, and of Ramrod's suspicions that Sharpey was a spy, Longman returns to the lab, against Oonagh's protests. Up to now, Sharpey had entered the isolation tank. It was Sharpey who jeopardized his sanity. Now, to find out what prolonged stays in the sensory deprivation tank can do to a man, and may have done to Sharpey, Longman takes the place of his dead friend.

.jpg) |

| Copyright Hamish Campbell/TSPL/Writer Pictures |

When we first meet Longman and Oonagh, and learn of the virginal Tate's love for her, it seemed to me that this was merely another example of mature domestic matters standing alongside, or perhaps even overshadowing, the genre plot that you thought was going to be the thrust of the thing -- this isn't uncommon in English fiction from this general era. You can find this kind of domestic drama sharing center stage in horror novels as diverse as Simon Raven's Doctors Wear Scarlet and Kingsley Amis's The Green Man. In The Mind Benders, however, it's not a matter of one thing sharing center stage with the other as it is the domestic drama actually being the center stage on which the genre material performs. Or vice versa. I haven't figured out which it is.

Anyhow, while Sharpey's story is resolved, it's what the isolation tank does to Longman, and by extension Oonagh, that is the reason the book exists at all. Suffice it to say, what it does to Longman is unpleasant, but while Kennaway himself makes the Jekyll and Hyde comparison he does so only in passing. Even though at times for the reader it will remain to be seen how badly Longman's personality has been twisted, in other words, how far, how evil, he will become, what's unsettling about The Mind Benders are the moments of almost homey cruelty, the kind of casually nasty remark by Longman about Oonagh, and heard by third parties, to whom these comments are often addressed, that may remind the reader of actual domestic nastiness they may have witnessed, or experienced.

So the idea of "sensory deprivation" becomes a rather clean metaphor for what it takes, psychologically as well as in relation to actual senses, for a man to not ruin what he has. A man specifically -- I don't know when Kennaway's wife cheated on him with John Le Carré, but it would be interesting to know how it coincides with The Mind Benders. Was the novel a somewhat disguised attempt to address that part of his life, or is it merely a coincidence? Or a foretelling? The novel's end is not its strongest bit. Too much of the dialogue comes pretty close to being of the "These are our themes" variety (there's also symbolism involving a dog that is at once obvious, silly, but somehow successful, possibly because Kennaway kind of throws it away), and things conclude too neatly. I wonder if Kennaway wasn't sure if he should really go for it. As a matter of fact, as Paul Gallagher writes in the introduction to the Valancourt Books edition, The Mind Benders was written specifically as a companion to the Basil Dearden film -- in effect Kennaway novelized his own original script, as Elmore Leonard did with Mr. Majestyk and Budd Schulberg did with Waterfront. If he was unable to go beyond a certain point with the film, perhaps a need to remain faithful to the screen version forced him to go easy in the novel as well. I don't know. But even if the novel The Mind Benders peters out a little bit at the end, the rest of it remains an unusual and gripping genre novel, not about spies or violence, but about marriage. Which I think we can agree is an unlikely thing for a genre novel to be about.

Labels:

James Kennaway,

The Mind Benders,

Valancourt Books

Sunday, August 3, 2014

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)