---------------------------------

DENNIS: Bill, it has been a tremendous amount of fun trading thoughts with you this week on The Man Who Wasn’t There, even if we managed to schedule the conversation during a week in which the deadlines and demands of the outside world of work made it maybe a little more difficult to dig in than we would have liked. And those “real-life” demands are making themselves felt even on this Sunday, a designated day of rest, if I’m not mistaken, one whose status as such has never made much of an impression upon the forces that make my breadwinnin’ work available to me. (Over the past 20 years those forces haven’t been significant respecters of any free time-type hours outside the usual eight or nine demarcated in the average American workplace. But hey, at least I’m getting paid!)

So if you will indulge, and if the notion doesn’t seem particularly slovenly in the shadow of your previous, meticulously considered near 2,000-word response, I’d like to offer an answer to your final question, “How do we close this out?” with a few brief comments followed by a gallery of striking images from the movie that I found galvanizing, haunting or just plainly beautiful, accompanied by some explanation as to why.

I was really grateful for you mentioning the business of shaving. I don’t recall if I’d made a mental note of it during previous screenings, but this time the connection between Ed shaving Doris’ leg in the bathtub and later Ed’s own casual observation of the executioner shaving the patch on his calf where the electrode would be placed really impressed me. And it’s not just the shaving. We see Ed’s leg being cleaned, and that’s followed by a glance toward the bucket where, much the same way as Ed did with Doris, the executioner rinses the razor in a slosh of soapy, hairy water. You ask if I think Ed perceives Doris as being there with him. I’m not sure I made that kind of inference (and that may be due to what I bring to the table, an indicator of my own spiritual inclinations) so much as that I saw Ed reflecting, in the much the same way as he subconsciously does during that remembrance of Doris rebuffing the salesman and then coming inside for a disengaged sit-down on the couch, on his relationship with her. (He does speculate that she might be where he’s going, wherever that might be, and expresses the hope that he might be able to tell her how he feels, about her, about the world, in a way he never could during their corporeal time together.)

What’s moving about this remembrance, coming in his last moments as it does, is its quality of genuine warmth. Unlike the dream of Doris returning not so much to him but to her glass of bourbon, enduring his company as a necessary evil, as an uncomfortable aspect of the comforts of home, this remembrance harkens back to the one moment of genuine intimacy the movie affords to Ed and Doris. It comes in the moments after Ed’s first meeting with Tolliver, when he’s first beginning to turn the idea around in his head about somehow getting the money to invest in Tolliver’s dry-cleaning proposal. He muses to himself about the convenient process involved (“It was clean. No water. Chemicals.”) while he soaps and shaves the leg belonging to the woman whose infidelity will eventually inspire his impulsive scheme to extract the necessary cash from her lover, Big Dave. So it’s an intimate moment, however tinged with betrayal and suppressed anger. But in Ed’s reflection upon it as he approaches the Big Sleep, the moment itself seems cleansed of resentment, suffused with regret and even apology, the prickly stubble of a bad marriage washed away by the hope of an unlikely future, or at least the desire to reconnect with what was ever good about the marriage in the first place. It’s hard to imagine trying to insist on the heartlessness of the Coens in light of this lovely strand of emotional acuity, even as they use the most unlikely of imagery in order to express it.

Someone wrote me earlier in the week, when this discussion first started and suggested that to him The Man Who Wasn’t There was, instead of a spiritual twin to A Serious Man, a black-and-white remake of Barton Fink. Though the comparison may have rewards of the sort that we’re talking about here that I just haven’t thought through, it also seems inapt in some significant ways, the primary one being that there’s a big difference between feeling the noose tighten around one’s neck over a case of writer’s block—one’s own pretense to literary and artistic value being a contributing factor to the sense of impending doom—and not having anything even resembling talent or the opportunity of expression to fall back on during the inexorable dip into the abyss. It’s been a long time since I’ve gone back to the Earle Hotel, and truthfully I haven’t felt much compulsion to do so in the years that have passed since I saw Barton Fink for the first time. It’s always seemed to be to be the Coens’ most facile movie, dismissive of the idea of literary sincerity, either from a theatrical specimen like Fink (a stand-in for Clifford Odets) or from a boozy, dissolute figure like William Faulkner, and the strangeness of the Coen touch (the peeling wallpaper, the life of the mind, et al) always struck me as being a little too in love with the influence of David Lynch, who was heavily in vogue with Twin Peaks during the movie’s production and release. In other words, the movie many might first think of as being quintessentially Coen-esque is, to me, one of their least genuine. (I think of Barton Fink as their fanboy movie.) There are many things to like, even love about it-- Tony Shalhoub’s Ben Geisler being primary among them, as you point out. (I tried finding video clips of Shalhoub’ brilliant harangues in this film, but each one came tethered to an announcement which told me that I could not view the clip in my country. I see…) But the brand of fatalism being peddled in Barton Fink has always seemed imposed rather than earned, as it does in The Man Who Wasn’t There and A Serious Man. That said, given that my attraction to their work as filmmakers is largely one in which even their worst is better than the strained efforts of their many imitators (and even many who have no interest in imitating them), I will concede that it deserves another look, one which, being 20 years removed from that Lynch-saturated cultural atmosphere, may reveal things I’d never seen before.

And to answer my own question, because whether I like it or not Barton Fink is clearly more than a pastiche, I can’t put it at the very bottom of my Coen ranking. And can’t put The Hudsucker Proxy there either—it’s a movie I like much more than I do Barton Fink, but it’s been even longer since I’ve seen it than it’s been since I’ve seen the other, so I’ll have to refrain from any real judgment on it of this sort on it. I’ll reserve the bottom spot for Blood Simple, a movie that has always seemed like not much more than a Hollywood calling card to me, clever to be sure, but also exactly the kind of Post(modern)man Always Rings Twice reference manual that The Man Who Wasn’t There fastidiously avoids becoming. Blood Simple has the earmarks of the technical brilliance to come, but it’s an precocious, immature movie and the shadow of all those film noirs runs too deep for the brothers here— it took moving into the realm of a completely different, sun-splashed world, that of Raising Arizona, for them to find their true, original voice and escape the traps of cool pastiche. Blood Simple gets my vote for my least favorite Coen Brothers movie.

Okay, last call. The Man Who Wasn’t There is such a visually rich movie, and we’ve spoken so often in this exchange of ideas about story and character that find their expression in the richness of visual imagination that the Coens and their peerless director of photography Roger Deakins bring to the movie, that I thought it would be appropriate, and fun, to end off this series with a gallery of some of those images, accompanied by a brief line or two of appreciation. A couple of these will have most certainly already shown up here or at your place, but that’s okay. Beauty shouldn’t be restricted to a single glance.

There's something incredibly warm and sympathetic about the way they light and frame Doris in this scene when Ed first comes to visit her after her arrest. The hint of a shiner on her right eye, never explained, adds to the poignancy.

I love the offhanded way Birdy and the boy regard Ed when he talks with them outside the piano recital. It's clear they are doing their best just to indulge him until he extricates himself from the scene.

Detective Burns (Jack McGee), the gumshoe Riedenschneider hires to get the deep background on Big Dave Brewster. Visually perfect.

"You know how Big Dave loved camping and the out of doors?" "Yeah."

"We went camping last summer in Eugene, Oregon. Outside Eugene..."

Everything you need to know can be found in contemplating the haircut...

Deakins employs an extraordinary long-lens tracking shot to observe Ed swimming against the tide of humanity and his own despair, already unable to remain afloat in the wake of Doris’s arrest. “When I walked home it seemed like everyone avoided looking at me, as if I’d caught some disease. This thing with Doris-- nobody wanted to talk about it. It was like I was a ghost walking down the street.”

Dark shadows...

"I killed him."

Ed's sophisticated dinner manner (what the Coens have called his talk show host pose) cannot disguise his contempt or his disinterest...

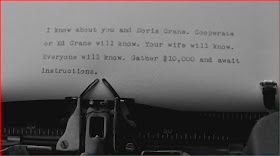

The note.

A guard peers at Ed from outside Ed's cell...

A car crash unlike any other. The sequence in which Ed, distracted by Birdy's advances, drives off the side of the road, rendered anything but routinely by the Coens' consummate command of the power and clarity of their images. I love how they use this sequence to visually tie into the UFO motif that informs the second half of the film:

Finally, another moment of curdled intimacy between Doris and Ed. Early on in the film, as they are preparing to attend the Nirdlinger Christmas party, Doris asks Ed to "zip me up," a moment of casual companionship familiar to most couples. Yet this one, with its slow track in on Doris's back, sights on the open dress, and Ed's deliberate act of compliance, has about it one part intimacy and two parts foreboding, as if Ed were zipping Doris not into a dress but into a body bag, which metaphorically, of course, he will soon do.

On that note, Bill, thanks once again for a lively and rewarding exchange. Let's consider this conversation zipped up. Next year, Roller Boogie?

No comments:

Post a Comment