Friday, November 22, 2019

Saturday, October 5, 2019

A Source of Innocent Merriment

In the song "A More Humane Mikado," from the operetta The Mikado by Gilbert & Sullivan, that character, the Mikado, a Japanese emperor, believes himself, and proclaims himself, to be entirely sympathetic, unquestionably so, while going on to list all the different ways he will suitably punish the various criminal types whose fates fall within the scope of his rule. The Mikado being light opera, many of the punishments are rather silly, though, crucially, not all ("The advertising quack who wearies/with tales of countless cures/his teeth, I've enacted, to be extracted/by terrified amateurs"); moreover, the crimes for which many of these citizens are being punished are hardly crimes at all -- women who dye their hair, "idiots" who write on train windows, bad singers. Add on top of this the Mikado's insistence on his own humane nature and essential goodness, and not only that, but that his pursuit of these questionable punishments is actually evidence of his basic human decency ("A more humane Mikado never did in Japan exist/To nobody second I'm certainly reckoned a true philanthropist/It is my very humane endeavor to make, to some extent/each evil liver a running river/of harmless merriment) and the audience for this 1885 musical can't help but conclude that this man positively exhales great clouds of disingenuousness.

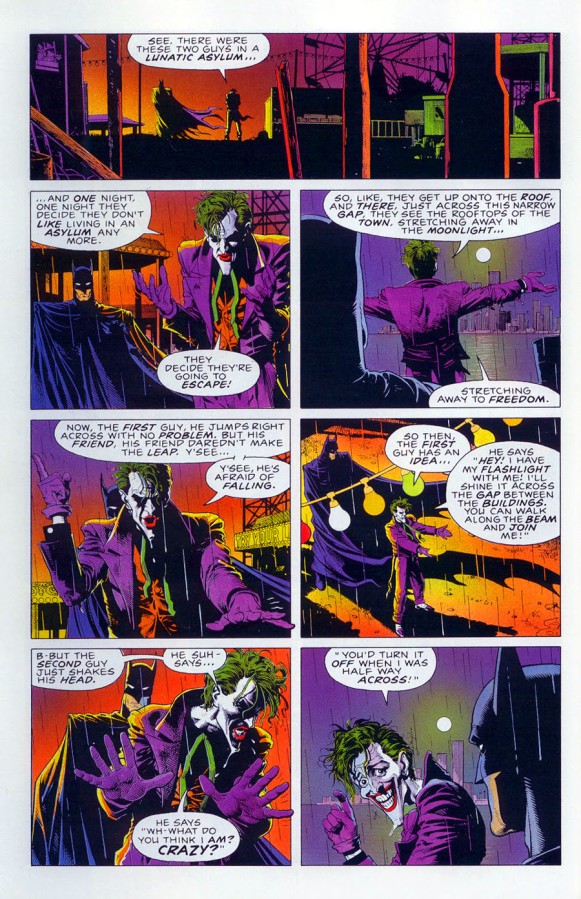

Jump ahead 134 years. Todd Phillips, our modern W.S. Gilbert, and previously the director of the scam documentary Frat House, such decent but disposable comedies as Old School, and such empty, insulting shock-banality comedies as The Hangover Part 2 (the first Hangover film having begun, if one is being generous, in the "decent but disposable" category before being spaghettified by the black hole of its successor; both of them have since collapsed into The Hangover Part 3 which may not exist) has now, Todd Phillips has, won the Golden Lion at this year's Venice Film Festival. The Venice Film Festival is no joke, as these things go, and the Golden Lion is its equivalent of the Palme d'Or. Past winners include Agnes Varda's Vagabond and Eric Rohmer's The Green Ray. Phillips won it for Joker, about the evil clown villain who is Batman's archnemesis. I myself am a great fan of the Batman character, as well as the Joker. Well, I'm not a fan of the Joker, but he's a great character -- at his best he's weird, and funny, and actually frightening, a hyper-verbal genius who has somehow turned Vaudeville into violence, and who will do anything. The Joker has changed over the years, becoming more grim and nihilistic since Batman himself shed his 60s goofball frivolity and reclaimed his noir-ish freakshow roots in the 1970s. The Joker has followed suit to become a figure of true evil in the comics and in his various cinematic incarnations, most notably in Christopher Nolan's 2008 film The Dark Knight, in which Heath Ledger gave a tremendous performance as a twitchy, mysterious, vile, murderous comedian who, we're told in arguably the film's most famous line, "just wants to watch the world burn." So that's where we were basically with the Joker when Todd Phillips got his grubby mitts on the character and thought "Well I'm the most cynical asshole on the planet, let's see what this gets me." Hello, Golden Lion!

The phenomenon of Joker is something that...well, listen, I can't be a hypocrite about this. I've engaged in the online hullaballoo, and have made my doubts about Phillips's movie, sight unseen, very clear. I've also made very clear that critics who run through the streets like Kevin McCarthy, begging anyone within earshot to heed their warnings about the violence movies like Joker will without a doubt inspire its dunderpated audiences to commit (it used to be conservatives who did this, which meant it was paranoid and authoritarian; now its liberals, which means it's fine) are condescending fear-mongering, sniveling, cowardly little shits. But having now seen the film, I want to make it even more clear that it has become impossible for me to engage in the discourse about Joker any longer because it doesn't deserve even the stupid fucking arguments people have been having about it. Joker has absolutely zero going on in it, it is thoughtless, frequently dull, silly, anticlimactic, a waste; it's thieving, insincere, stupid, carpetbagging nonsense. With a couple of good shots that as far as I know Todd Phillips came up with all by himself.

The film stars Joaquin Phoenix, one of our great actors, as Arthur Fleck, a sort of, I don't know, clown for hire? Who works for a sort of clown subcontractor, hiring guys like Fleck out to dress up in clown gear and hold signs outside of their stores, or perform at children's hospitals. You know, a clown subcontractor. From frame one of Joker, we know that Arthur Fleck is mentally ill. We will eventually learn some specifics, such as that he has a condition which, in moments of extreme stress, causes him to laugh uncontrollably, despite laughter being at odds with his mood. He has a laminated card he hands to people who might be startled by this. He lives with his mom (Frances Conroy) in a scummy little apartment in the middle of Gotham City. They're very fond of each other, but his mom can't stop bringing up local billionaire Thomas Wayne, to whom she frequently writes letter, but from whom she never gets a response. At night, the two of them, otherwise lonely, bond over a late night talk show, hosted by the Johnny Carson-esque -- or rather, the Jerry Langford-esque (but actually resembling neither) -- Murray Franklin (Robert De Niro). Franklin is Fleck's hero. Fleck is an aspiring stand-up comic, in addition to being a clown. But unlike any other character in the history of cinema, Fleck's dreams of comedy success are badly hindered by his mental illness. He regularly sees a social worker (Sharon Washington), but funding's about to be cut, and Fleck won't be able to get his pills anymore. And he keeps getting beat up. Then again, he seems to have made a connection with a neighbor in his apartment building (Zazie Beetz). But on the other hand he keeps getting beaten up. One night, after being fired from his children's hospital gig for carrying a gun, he's on the subway when three of those Wall Street Guys, you know the type, start making fun of a woman and throw what appear to be Cheetos at her. Arthur starts acting weird, so the Rich Fellows decide "Let's destroy this guy" and they start harassing Arthur, but then Arthur pulls that gun he had and shoots them all to death.

I'll try to speed through the rest of the relevant plot summary. This triple murder, committed by a clown against three Rich Fellows (aka Wall Street Guys) somehow instantly inspires the creation of a massive city-wide protest, with citizens dressed as clowns holding signs that say "Resist" (held upside down! How punk!) and "We Are All Clowns", which is doubtlessly true. But I'm not kidding, this happens overnight. If Todd Phillips's aesthetic approach was (God forgive me) "gritty realism," then shouldn't some of this make any sense at all? There's no build up to any of this. After maybe 40 minutes of boredom involving Fleck's sad inactivity, Joker leaps into full-on "Gotham is ablaze!" mode. The same can be said for Fleck's relationship with Zazie Beetz's Sophie, although that bit has a twist to it, which might seem obvious. But the fact that what is revealed about their relationship plays as a twist (and here's the twist: they're not in a relationship, Fleck imagined it all, and it turns out Sophie is frightened by him) means that Phillips, that fucking numbnuts, thought that the two of them being in love, as he presented it, somehow worked, that it played, even though Sophie is a normal person raising a child by herself, and Arthur is never depicted as anything other than, at best, a genial psycho, and that when he pulls back the curtain, by which I mean, when he steals from M. Night Shyamalan, he thinks we should be thinking "well what the fuck I thought they'd spend eternity together."

Speaking of stealing. Before he "left" comedy (about which more in a bit), and in between Hangsover, Todd Phillips released Due Date, a film that is a naked rip-off of John Hughes's Planes, Trains, and Automobiles. Evidently pleased by how that all worked out for him, Phillips decided his narrative and aesthetic approach to Joker (which he co-wrote, as well as directed) should be to graft large chunks of classic Martin Scorsese films onto the two ideas he had (those two ideas being Arthur Fleck's laughing disorder, and to sometimes have Fleck walk into a room, point the camera up at him from the floor, and move it around a bit), and then sort of just shove it in front of an audience. Because, I mean, that Zazie Beetz stuff is just a bad version of the De Niro and Diahnne Abbott material from Scorsese's King of Comedy, a film which is also the source of all the talk show stuff in Joker. And the PTSD/violent retribution stuff from Taxi Driver, etc. Everybody knows this before they even see Joker. It's shameless, and because the marketing has led with this, it's not even interesting. You can't even say "Aha, you brigand" because, smirking cynic that he is, Phillips got ahead of it. He gets to "be" Scorsese (he won the Golden Lion!) by being the opposite of Scorsese, by innovating nothing, by adding nothing. Phillips's shield is that he roped Scorsese in to help him line up Emma Tillinger Koskoff, Scorsese's producing partner, to work on the film. Had John Hughes not already been dead when Phillips was making Due Date, a similar arrangement would have surely been made.

A good hint of what's to come can be found right at the beginning, in the opening credits font. It's a kind of old-fashioned curlicue which I think might be meant to evoke Vaudeville but actually, to me anyway, brought to mind fairy tales, but in any case is "ironic" in the "oh that font is fun, but that guy just got beat up while I was enjoying the font" sense. This is more or less the cinematographic philosophy throughout. The two good shots are the one from that early poster, the one of Joaquin Phoenix in his Joker makeup, enveloped by that municipal green paint and boiler room-lighting, arms up, appearing to be caught in a moment of almost religious grace (this is one of those shot-from-below bits I mentioned earlier, and it does pay off, however briefly). The other comes late in the film, after the Joker commits an act of violence which cannot be hidden. Again he's in full makeup, and in his full purple suit (the Joker look designed for this film is a good one, I'll admit that much), now with blood on his face. That's a cliché, but the shot is almost of Phoenix's profile -- he's smiling and trembling at once. It's the trembling that makes it all work. Phoenix seems to be actually shaking in the adrenal aftermath of a life- and mind-changing explosion. It's Phoenix's best moment, from a performance that is otherwise fine, but a pale shadow of his work in films that ask much more of him. I would, for instance, defy anyone to point to a role and performance that is anything like what he was asked to do, and did, in Paul Thomas Anderson's The Master. In comparison, Phillips seems to have said "Okay, be crazy, but quiet. And...action!"

Which is another thing: why make a Joker film, and make the character so inarticulate? In the comics, and in the various Batman films in which the character has appeared, The Joker is a chatterbox, gleefully, maliciously, verbal. That's a big part of the idea -- the guy makes a lot of jokes! In Joker, Arthur Fleck is, to borrow a line from a film made by one of Phillips's "key" "inspirations," a mumbling, stuttering prick. He can barely finish telling a joke. We see him do stand-up once, after he's gone off his meds and is just a total mess. If we're going to have The Joker explained to us, then maybe make his interest in comedy a little bit more a part of it all. Better a little bit, than nothing. Anyway, a video of that stand-up performance, which is disastrous, makes its way to Murray Franklin, who plays it on his show, which leads to the film's climax. Which is very violent, and rides the wave of that sudden revolutionary impulse among Gothamites that Joker's random train murders began, and which includes a surprising amount of Batman lore. All of which I found utterly ridiculous. "Is that fucking Alfred???" I asked myself at one point. And then at the end I got to watch Phillips pilfer Frank Miller. It's all nonsense, the film so obviously believes it's above comic books and comic book films, yet relies on them for its big boost at the end.

I mean, if you refuse to show The Joker making jokes (with all his shots of Phoenix all decked out in purple walking in slow-motion while Gary Glitter(!) plays, or etc., Phillips seems more interested in making him look cool), to show him being funny while he's being vicious, then why is any of this even happening? But of course, Todd Phillips is serious now. In a recent interview, Phillips said that he stopped making comedies because what with "wokeness" and "cancel culture," it's impossible to be funny anymore. I'm fairly conflicted about this, because I don't tend to like the kind of comedy that Phillips argues has been ruined by the current political climate, but, on the other hand, I sometimes do, and I think those who wish to do away with it are breathtakingly hypocritical, lacking in self-awareness to such a degree that they might literally fade into nothing. But also a bullshit hypocrite is Phillips. Early in the film there's a scene where Arthur goes to a comedy club, as part of the audience. Performing that night is Gary Gulman, an actual stand-up, and playing himself, in a sense, because he's doing one of his own routines, a bit that, if you keep up with current stand-up at all, is pretty well-known. It's an extended piece, ostensibly about the sexual role play Gulman and his wife engage in, involving a male professor and a female student, but which very quickly becomes an extended complicated story about the difficulties of being a professor dealing with a difficult student, a story that almost instantly sheds any and all sexual connotations. It's very funny, and very clean. It's absurd, and is guaranteed to offend not a single person on earth. So if Phillips thinks comedy is impossible now, why is he aware of, and why does he approve of, Gary Gulman? And approve of his comedy so much that he puts Gulman in his film doing one of his own bits??

Probably because, as others have said, Phillips doesn't believe a goddamn word he says. "Meaning what I say" isn't part of the plan. "Saying it" is enough. This goes for the sympathy his film pretends we're supposed to feel for Arthur Fleck. That sympathy, or the idea of it, is what's caused the film to become such a controversial piece ever since Warner Brothers released the first trailer. But it's all a hoax. It's a scam. Why everybody at the Venice Film Festival bought into it, I don't know, but I guess Don't Look Now, The Comfort of Strangers, and Robert Aickman were right. But when you create (using that word loosely) a character who is mentally ill, and have him kill only people the audience is meant to hate, and who have done him, this poor fellow, wrong, and pretend, then, as Phillips has done, that the audience isn't meant to (this doesn't mean they will) approve of this behavior, at least as a piece of entertainment, then you're having it both ways, or trying to, which means you're lying. And again, I think the critics predicting violence in the wake of Joker's release are behaving reprehensibly (the only group I'm aware of who has reacted to the film with frothing positivity are the critics who saw it in Venice). But, Phillips will insist, do not criticize me, for I have behaved nobly. My object all sublime, I shall achieve in time, to let the punishment fit the crime, the punishment fit the crime. And make each prisoner pent, unwillingly represent, a source of innocent merriment, of innocent merriment.

Saturday, February 2, 2019

Oh, This is Terrible: New Capsule Reviews

I've been sorta kinda easing back into writing reviews, and my website of choice, for some bizarre reason, has been Letterboxd, not my own. I'm probably going that route because I know at least some people will see them there, whether they want to or not, just by scrolling through their activity feeds, but it's rather perverse to let my own blog lie fallow while I do that, especially since I like to think there are people who still check this blog who don't follow me on any other website. So I'm going to try and perk this place up by bringing over the relatively-speaking "best of" reviews from over there and post them here. I'm going with the four longest ones, because they also happen to be the ones most worth reading (again, relatively speaking), but the result of this is that I'm including reviews of Lethals Weapon 2 and 3, but not 4 or the original. I watched all four over the course of about a week and a half, and wrote something about all of them, but there's not much going on in those other two "reviews." So they're out! Okay, preamble over. Enjoy, or don't!

Living in Oblivion (d. Tom DiCillo) - It's probably emblematic of something or other that at the height of the 1990s American Independent Cinema boom, a subgenre was spawned within the movement of films about how hard it was to make American independent films. There was Living in Oblivion, In the Soup, My Life's in Turnaround...so that's three right there. You might call this little corner of 90s film "insular," perhaps, or "Ouroborosian," and you might wonder why the filmmakers behind them couldn't have maybe waited a few pictures into their careers before ceasing to look beyond their own noses.

Living in Oblivion (d. Tom DiCillo) - It's probably emblematic of something or other that at the height of the 1990s American Independent Cinema boom, a subgenre was spawned within the movement of films about how hard it was to make American independent films. There was Living in Oblivion, In the Soup, My Life's in Turnaround...so that's three right there. You might call this little corner of 90s film "insular," perhaps, or "Ouroborosian," and you might wonder why the filmmakers behind them couldn't have maybe waited a few pictures into their careers before ceasing to look beyond their own noses.

Well, my feeling is, tomorrow is not guaranteed, and as a writer or filmmaker or any other kind of artist, you have to follow whatever idea has its hooks into you at the moment. Besides, in the case of Tom DiCillo's Living in Oblivion, the film he made previous to it came out four years before. Making movies is hard, and beginning to make a movie is probably harder.

I have to say, I don't buy DiCillo's claim that the character played by James LeGros in this movie is not based on Brad Pitt, the star of DiCillo's Johnny Suede -- not because LeGros's Chad Palomino jibes with what I know about Pitt (if pressed, I might be forced to admit that fundamentally I don't know anything about Brad Pitt) but because, well...Brad/Chad. "Pitt" and "Palomino" both start with a P. Blonde hair. That sort of thing. The only really strong argument against it that I can see is that when DiCillo and Pitt were making Johnny Suede, Pitt was nothing like the movie star he would become (Thelma & Louise came out the same year), and the state of movie stardom is intrinsic to the character of Chad and his behavior. And not just, I don't think, of the "I'm going to BECOME a movie star, so you might as well treat me like one now" variety. But what do I know.

I didn't see this movie (or In the Soup or My Life's in Turnaround) when it came out, which strikes me as odd now. The '90s is when my cinephilia blossomed, as it did for so many other people of my generation, may God have mercy on us all, so you'd think in my youthful myopia, movies about movies would be a thing I'd be drawn to, like booze and pictures of naked women. But somehow, no. Of that clutch of films, Living in Oblivion is without question the one that has lingered longest in the minds of the kind of people who would have seen it in 1995, and was, I think, the most successful at the time. So I'd probably heard of the dwarf dream sequence bit, and I'd like to think my take was that it was a hack joke, and this was enough, Steve Buscemi or no Steve Buscemi (who of course by then I already loved), to drive me away. The problem has turned out to be that while I'm not entirely sure if DiCillo knew that a dwarf dream sequence is a hack joke, his approach to it, and Peter Dinklage's performance, make it better than the idea deserves. It turns out to actually be funny.

As is James LeGros, come to think of it, and several other people in the cast. Much to my dismay, this film, which could not be more stuck in its time, actually works, and is funny, and even kind of interesting here and there. And boy do I still love Steve Buscemi.

Lethal Weapon 2 (d. Richard Donner) - In case you've forgotten, this is the one that begins with the Warner Brothers logo coming up with the Loony Tunes theme playing behind it, and then turns out to be about Apartheid. You'd think in that case that Murtaugh would be foregrounded, but no: Riggs has to have a second woman he loves get murdered before he can get over the death of the first one. He does, though, and he and Murtaugh also get over the deaths of, like, eight of their cop buddies. These murders are intercut with Murtaugh goofing around with Joe Pesci, and Riggs having sex with Patsy Kensit while making jokes about his dick. So tonally, Lethal Weapon 2 is a bit of a goon show.

The scene where Murtaugh is stuck on a toilet because if he stands up a bomb will explode him is actually pretty good, with good, touching friendship business between him and Riggs. On the other hand, at one point in that scene, Murtaugh says his toilet reading was the new issue of "Saltwater Sportsman" and Riggs says "Is that the one with the article about deep sea fishing?" Wouldn't every issue of "Saltwater Sportsman" have an article like that in it? And Riggs wasn't being a smart aleck, either, because when he says "Is that the one with the article about deep sea fishing?" Murtaugh says "Yeah." Come on, guys.

I also like the scene where Riggs tells Darlene Love about the night his wife died. It's a nice little moment, and I like how close Riggs is with the whole Murtaugh family. It's moving! And overall I think of Lethal Weapon 2 rather fondly, even though it includes one of my most hated film cliches: a guy picks up his TV remote, turns the TV on, and begins laughing immediately at whatever show is on. That's what aliens or psychopaths who've never laughed do when they've incompletely absorbed the visual information of normal humans laughing at TV comedy shows, and now want to assimilate. For what reason, we cannot know.

Lethal Weapon 3 (d. Richard Donner) - Back in the 80s and 90s (and maybe still to this day), there was a particularly bothersome movie trope wherein, lacking either a villain or figure of mockery, Hollywood filmmakers would give that job to a character who, in reality, would be appreciated for their hard work in a thankless job. The most egregious example of this I can think of is the flight doctor played by Christian Clemenson in Apollo 13, whose concern for the physical health of the astronauts is meant -- because he's getting in the way of our good time and is just generally a drag -- to instill in the audience a boundless fury, leading us to scream "HE'S NOT GONNA GET THE FLU YOU FUCKING SON OF A BITCH!" at our screens.

The Lethal Weapon series of films carried on this tradition with the character Dr. Stephanie Woods, a police therapist working for the LAPD, played by Mary Ellen Trainor. In the first film, she's actually sort of taken seriously, in that she at least provides the grade-school psychiatric exposition to explain to us, the laymen, what kind of mind can be behind the wild eyes of Detective Martin Riggs. By Lethal Weapon 2, the attitude towards Dr. Woods is closer to "Go read your books, egghead, Riggs gets the job done!" and by Lethal Weapon 3 she's an oblivious clown who actually thinks she can help Murtaugh through the trauma of having to gun down an armed teenager. Jesus fucking Christ, lady, you're embarrassing yourself, Murtaugh is fine!

Otherwise, I found Lethal Weapon 3 somewhat less tedious than I'd remembered, although for about the first hour it piles on the cartoon bullshit like mad. Riggs and Murtaugh are busted down to uniformed beat cops after causing a building to explode, and Riggs threatens to murder a jaywalker before tearing after trigger happy bank robbers, within the first ten minutes. This is all played for a goof, but this being a Lethal Weapon movie, the tone has to at some point jump out of an airplane without a parachute and hope everything works out, so eventually we end up on Murtaugh's boat while Riggs tries to scream Murtaugh out of his post-shooting drinking binge.

That bit occurs sometime between the two scenes that were ripped off wholesale from, of all movies, Jaws. There's no beach, the plot doesn't revolve around sharks in any way (the plot's about an evil ex-cop who's building a house, I think), but let's randomly lift two of the most iconic scenes from one of the most famous films ever made. Nobody even says the word "jaws" in this thing.

Finally, given the two films that preceded it, it would have been really funny if Rene Russo's character had died.

Mikey and Nicky (d. Elaine May) - As I mess around with the idea of regularly writing reviews again, one of my objectives is to keep things short. The problem is that in the case of Mikey and Nicky, the most unlikely film Elaine May ever had anything to do with (a statement which may be nothing more than proof that I don't know the first thing about May, which is certainly a defensible position) is that there's almost too much to say.

If I wanted to limit my scope, and I do, I might home in on the scene where Falk as Mikey and Cassavetes as Nicky go see a woman (Carol Grace) who may have a mental problems, and who Nicky regularly has sex with. He gives her money, but tells Mikey she's not a prostitute, you have to tell her the money is a gift. Nicky has sex with her while Falk waits in the kitchen. Then when Mikey tries to make his move, she rebukes him, biting his lip during a kiss he forces on her. From here, the two men -- who, it becomes easy to forget, are gangsters -- fall easily into abuse, slapping her (Mikey) and chastising her as though she were a child (Nicky). Then, when they leave her apartment, they act as though nothing has happened, and May's camera falls in line. Or at least, nothing happened to her. The incident blows the two men's friendship apart, but their fight could have been about anything, money, a job, for all the woman exists for them as a living human still in her apartment, experiencing her own aftermath. This scene anticipates one in Terry Gilliam's not-entirely-dissimilar Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, when the true danger and vile natures of Dr. Gonzo and Raoul Duke are revealed in a scene where Gonzo menaces a waitress played by Ellen Barkin, in front of an indifferent Duke.

And see later, too, when Nicky visits his wife (Joyce Van Patten), and from her body language it's clear that, while he doesn't hit her now, he's hit her before. Or when Mikey goes home to his wife (Rose Arrick), who, during their long talk, frequently shifts her conversational gears, placating and apologizing to keep her husband's temper in check, even though she hasn't done anything to raise it. It's morning, and she has a day to get through just like everybody else; why let it begin like this if she can possibly help it? Well, she ain't seen nothin' yet, of course.

I believe Mikey and Nicky would face rough sledding were it to come out today, because it depicts two pigs, not so much without judgment, but with its judgment concealed beneath an almost shocking amount of sincere empathy. These scenes of misogyny are surrounded by a film about the humanity of these two pigs. And somehow, May doesn't sneer. She could, and she'd be justified, but she doesn't. Nowadays, you'll get bashed for seeing the humanity inside those we have every reason to despise. So thank God Mikey and Nicky was made when it was, at the only time it could be.

Living in Oblivion (d. Tom DiCillo) - It's probably emblematic of something or other that at the height of the 1990s American Independent Cinema boom, a subgenre was spawned within the movement of films about how hard it was to make American independent films. There was Living in Oblivion, In the Soup, My Life's in Turnaround...so that's three right there. You might call this little corner of 90s film "insular," perhaps, or "Ouroborosian," and you might wonder why the filmmakers behind them couldn't have maybe waited a few pictures into their careers before ceasing to look beyond their own noses.

Living in Oblivion (d. Tom DiCillo) - It's probably emblematic of something or other that at the height of the 1990s American Independent Cinema boom, a subgenre was spawned within the movement of films about how hard it was to make American independent films. There was Living in Oblivion, In the Soup, My Life's in Turnaround...so that's three right there. You might call this little corner of 90s film "insular," perhaps, or "Ouroborosian," and you might wonder why the filmmakers behind them couldn't have maybe waited a few pictures into their careers before ceasing to look beyond their own noses.Well, my feeling is, tomorrow is not guaranteed, and as a writer or filmmaker or any other kind of artist, you have to follow whatever idea has its hooks into you at the moment. Besides, in the case of Tom DiCillo's Living in Oblivion, the film he made previous to it came out four years before. Making movies is hard, and beginning to make a movie is probably harder.

I have to say, I don't buy DiCillo's claim that the character played by James LeGros in this movie is not based on Brad Pitt, the star of DiCillo's Johnny Suede -- not because LeGros's Chad Palomino jibes with what I know about Pitt (if pressed, I might be forced to admit that fundamentally I don't know anything about Brad Pitt) but because, well...Brad/Chad. "Pitt" and "Palomino" both start with a P. Blonde hair. That sort of thing. The only really strong argument against it that I can see is that when DiCillo and Pitt were making Johnny Suede, Pitt was nothing like the movie star he would become (Thelma & Louise came out the same year), and the state of movie stardom is intrinsic to the character of Chad and his behavior. And not just, I don't think, of the "I'm going to BECOME a movie star, so you might as well treat me like one now" variety. But what do I know.

I didn't see this movie (or In the Soup or My Life's in Turnaround) when it came out, which strikes me as odd now. The '90s is when my cinephilia blossomed, as it did for so many other people of my generation, may God have mercy on us all, so you'd think in my youthful myopia, movies about movies would be a thing I'd be drawn to, like booze and pictures of naked women. But somehow, no. Of that clutch of films, Living in Oblivion is without question the one that has lingered longest in the minds of the kind of people who would have seen it in 1995, and was, I think, the most successful at the time. So I'd probably heard of the dwarf dream sequence bit, and I'd like to think my take was that it was a hack joke, and this was enough, Steve Buscemi or no Steve Buscemi (who of course by then I already loved), to drive me away. The problem has turned out to be that while I'm not entirely sure if DiCillo knew that a dwarf dream sequence is a hack joke, his approach to it, and Peter Dinklage's performance, make it better than the idea deserves. It turns out to actually be funny.

As is James LeGros, come to think of it, and several other people in the cast. Much to my dismay, this film, which could not be more stuck in its time, actually works, and is funny, and even kind of interesting here and there. And boy do I still love Steve Buscemi.

Lethal Weapon 2 (d. Richard Donner) - In case you've forgotten, this is the one that begins with the Warner Brothers logo coming up with the Loony Tunes theme playing behind it, and then turns out to be about Apartheid. You'd think in that case that Murtaugh would be foregrounded, but no: Riggs has to have a second woman he loves get murdered before he can get over the death of the first one. He does, though, and he and Murtaugh also get over the deaths of, like, eight of their cop buddies. These murders are intercut with Murtaugh goofing around with Joe Pesci, and Riggs having sex with Patsy Kensit while making jokes about his dick. So tonally, Lethal Weapon 2 is a bit of a goon show.

The scene where Murtaugh is stuck on a toilet because if he stands up a bomb will explode him is actually pretty good, with good, touching friendship business between him and Riggs. On the other hand, at one point in that scene, Murtaugh says his toilet reading was the new issue of "Saltwater Sportsman" and Riggs says "Is that the one with the article about deep sea fishing?" Wouldn't every issue of "Saltwater Sportsman" have an article like that in it? And Riggs wasn't being a smart aleck, either, because when he says "Is that the one with the article about deep sea fishing?" Murtaugh says "Yeah." Come on, guys.

I also like the scene where Riggs tells Darlene Love about the night his wife died. It's a nice little moment, and I like how close Riggs is with the whole Murtaugh family. It's moving! And overall I think of Lethal Weapon 2 rather fondly, even though it includes one of my most hated film cliches: a guy picks up his TV remote, turns the TV on, and begins laughing immediately at whatever show is on. That's what aliens or psychopaths who've never laughed do when they've incompletely absorbed the visual information of normal humans laughing at TV comedy shows, and now want to assimilate. For what reason, we cannot know.

Lethal Weapon 3 (d. Richard Donner) - Back in the 80s and 90s (and maybe still to this day), there was a particularly bothersome movie trope wherein, lacking either a villain or figure of mockery, Hollywood filmmakers would give that job to a character who, in reality, would be appreciated for their hard work in a thankless job. The most egregious example of this I can think of is the flight doctor played by Christian Clemenson in Apollo 13, whose concern for the physical health of the astronauts is meant -- because he's getting in the way of our good time and is just generally a drag -- to instill in the audience a boundless fury, leading us to scream "HE'S NOT GONNA GET THE FLU YOU FUCKING SON OF A BITCH!" at our screens.

The Lethal Weapon series of films carried on this tradition with the character Dr. Stephanie Woods, a police therapist working for the LAPD, played by Mary Ellen Trainor. In the first film, she's actually sort of taken seriously, in that she at least provides the grade-school psychiatric exposition to explain to us, the laymen, what kind of mind can be behind the wild eyes of Detective Martin Riggs. By Lethal Weapon 2, the attitude towards Dr. Woods is closer to "Go read your books, egghead, Riggs gets the job done!" and by Lethal Weapon 3 she's an oblivious clown who actually thinks she can help Murtaugh through the trauma of having to gun down an armed teenager. Jesus fucking Christ, lady, you're embarrassing yourself, Murtaugh is fine!

Otherwise, I found Lethal Weapon 3 somewhat less tedious than I'd remembered, although for about the first hour it piles on the cartoon bullshit like mad. Riggs and Murtaugh are busted down to uniformed beat cops after causing a building to explode, and Riggs threatens to murder a jaywalker before tearing after trigger happy bank robbers, within the first ten minutes. This is all played for a goof, but this being a Lethal Weapon movie, the tone has to at some point jump out of an airplane without a parachute and hope everything works out, so eventually we end up on Murtaugh's boat while Riggs tries to scream Murtaugh out of his post-shooting drinking binge.

That bit occurs sometime between the two scenes that were ripped off wholesale from, of all movies, Jaws. There's no beach, the plot doesn't revolve around sharks in any way (the plot's about an evil ex-cop who's building a house, I think), but let's randomly lift two of the most iconic scenes from one of the most famous films ever made. Nobody even says the word "jaws" in this thing.

Finally, given the two films that preceded it, it would have been really funny if Rene Russo's character had died.

Mikey and Nicky (d. Elaine May) - As I mess around with the idea of regularly writing reviews again, one of my objectives is to keep things short. The problem is that in the case of Mikey and Nicky, the most unlikely film Elaine May ever had anything to do with (a statement which may be nothing more than proof that I don't know the first thing about May, which is certainly a defensible position) is that there's almost too much to say.

If I wanted to limit my scope, and I do, I might home in on the scene where Falk as Mikey and Cassavetes as Nicky go see a woman (Carol Grace) who may have a mental problems, and who Nicky regularly has sex with. He gives her money, but tells Mikey she's not a prostitute, you have to tell her the money is a gift. Nicky has sex with her while Falk waits in the kitchen. Then when Mikey tries to make his move, she rebukes him, biting his lip during a kiss he forces on her. From here, the two men -- who, it becomes easy to forget, are gangsters -- fall easily into abuse, slapping her (Mikey) and chastising her as though she were a child (Nicky). Then, when they leave her apartment, they act as though nothing has happened, and May's camera falls in line. Or at least, nothing happened to her. The incident blows the two men's friendship apart, but their fight could have been about anything, money, a job, for all the woman exists for them as a living human still in her apartment, experiencing her own aftermath. This scene anticipates one in Terry Gilliam's not-entirely-dissimilar Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, when the true danger and vile natures of Dr. Gonzo and Raoul Duke are revealed in a scene where Gonzo menaces a waitress played by Ellen Barkin, in front of an indifferent Duke.

And see later, too, when Nicky visits his wife (Joyce Van Patten), and from her body language it's clear that, while he doesn't hit her now, he's hit her before. Or when Mikey goes home to his wife (Rose Arrick), who, during their long talk, frequently shifts her conversational gears, placating and apologizing to keep her husband's temper in check, even though she hasn't done anything to raise it. It's morning, and she has a day to get through just like everybody else; why let it begin like this if she can possibly help it? Well, she ain't seen nothin' yet, of course.

I believe Mikey and Nicky would face rough sledding were it to come out today, because it depicts two pigs, not so much without judgment, but with its judgment concealed beneath an almost shocking amount of sincere empathy. These scenes of misogyny are surrounded by a film about the humanity of these two pigs. And somehow, May doesn't sneer. She could, and she'd be justified, but she doesn't. Nowadays, you'll get bashed for seeing the humanity inside those we have every reason to despise. So thank God Mikey and Nicky was made when it was, at the only time it could be.