I watched some movies recently. Are they on video right now? Yes. All of them? Well no. But soon! Here, let me explain...

The Great Beauty (d. Paolo Sorrentino) - Last Tuesday, Criterion released Paolo Sorrentino's The Great Beauty, just a couple weeks after it won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language film. So clearly everything's coming up Sorrentino lately, just a couple of years after his previous feature, This Must Be the Place, starring Sean Penn as an aging glam rock 'n roll star turned Nazi hunter (for some strange reason, I haven't seen this yet) was met with some unhappy bafflement. And in truth The Great Beauty hasn't been greeted with only applause -- from what I've seen, it's a somewhat divisive films, and some of the unconvinced can be rather venomous. Why's that, I wonder.

The film stars Toni Servillo (absolutely sensational) as Jep Gambardella, a middle-aged writer whose one novel was published decades ago. It's been mostly forgotten, and he looks back on this young man's work with what Dennis Potter once called "tender contempt." Now Jep spends his time writing culture reviews and articles and living it up at night, his apartment, which overlooks the Coliseum, being one of what I must assume are many, many hubs of big-spending nightlife. But Jep's empty. He has a good time, but his mind is never far from a distant memory of Elisa (Anna Luisa Capasa), a girl he loved in his youth but hasn't seen in many years, and who, he learns from Elisa's husband, recently died, never having forgotten Jep.

All of which makes The Great Beauty sound like a rather tender story about aging and regret, which to some degree it is, but Sorrentino's film is also a colorful, grotesque, whirlwind attack on contemporary Italian obscenity, excess, and blindness. Though not precisely evil, things can get somewhat infernal back at Jep's place (a shot of a regular party guest realizing in horror that she's overdosing on cocaine is almost thrown away), and if Jep's fiddling while this all happens is self-aware, that doesn't excuse him. Sorrentino sets up his intentions rather ingeniously in the beginning, with a series of images depicting tourists as well as oblivious locals lounging against and clashing with the relics of the ancient world that are now scattered throughout Rome like trees or park benches. This modernity set against the ancient -- and Jep, possibly alone among his friends, does notice the past -- brings to mind Rossellini's Journey to Italy, which had George Sanders rushing away from his wife Ingrid Bergman so that he could enjoy Italy's nightlife while she wandered further into its past. Also evoke are Fellini, in various guises, and Antonioni, whose work in particular Sorrentino seems interested in trying to draw towards some kind of logical conclusion, and even Resnais, in Sorrentino's meaningless and almost frightening lost and wealthy characters, sprawled across the lawn.

The Great Beauty starts to have a tough time at about the ninety minute mark, around the time a particularly significant story development sends Jep reeling. Sorrentino appears to share Jep's struggle to right himself, and the film hit several points that feel like logical endings before skipping off in a new direction. And while The Great Beauty hardly resembles a film that was written with a screenwriting guide within easy reach (this is a good thing), it's hard not to imagine that Sorrentino doesn't now understand the pitfalls of introducing a vital character (I'm thinking of the 104-year-old nun, here) three-quarters of the way through your film. Be all that as it may, The Great Beauty nevertheless remains a sort of glorious act of flag-planting: Sorrentino has wrapped up the major landmarks of Italian cinema into one bemused, disgusted, sad, and hopeful package. The stain that is the prime ministership of Silvio Berlusconi has often been noted when discussing this film, and while that would logically be Sorrentino's inspiration, The Great Beauty is a greater and more sympathetic biopic than that man could ever hope to deserve.

L'Immortelle (d. Alain Robbe-Grillet) - Speaking of Alain Resnais, sort of, on Tuesday Kino Lorber's Redemption line will continue its Alain Robbe-Grillet revival with their release of writer/director Robbe-Grillet's 1963 debut L'Immortelle. Robbe-Grillet had written Resnais' Last Year in Marienbad a couple of years previously. That experience appears to have stuck with Robbe-Grillet, let's say, because frequently resembles that earlier film, prominently using, for example, the imagery of people standing completely still and spread over a confined landscape like chess pieces. It's been some time since I saw Last Year in Marienbad, but here the ultimate effect of this effect is one of almost horror-film unease. This partially despite, and partially because, of the fact that L'Immortelle is very consciously a crime thriller, or "crime thriller." Despite their clear relationship to one genre or another, I've found it almost impossible to comfortably categorize the Robbe-Grillet films I've seen so far, and it's no less difficult here, even though it's nowhere near as aggressively post-modern as Trans-Europ-Express, which I wrote bout earlier this year. In the case of L'Immortelle, Robbe-Grillet's story is a simple one. Jacques Doniol-Valcroze plays a man traveling through Turkey. He stops for directions and finds himself in the company of a mysterious woman played by Francoise Brion, with whom he naturally falls in love. There's much he doesn't understand about her, but she's game and alluring and then one day he can't find her. She doesn't answer his calls, she doesn't call him, or leave a message with his somnambulant landlady, nothing. Obsessed, he begins searching for her, and L'Immortelle begins to take on the air of the kind of thriller that might have been written by Patricia Highsmith, or if you were too high-falutin' to call it a thriller, maybe by Paul Bowles.

Doniol-Valcroze's quest, and the form it takes, is classic thriller material, but of course Robbe-Grillet's concept of where this should all end is all his own. Scenes repeat, but with different characters. A child seems to appear in two places at once (and the man witnessing this seems not the least bit alarmed by it). The barking of a Satanic gangster's two dogs can be heard at any time. An antiques dealer from whom Doniol-Valcroze purchased a strange and supposedly rare figurine assures him that the exact piece that has reappeared in his window cannot be the same one. And in fact I'm eschewing one bit of plot that occurs about halfway through and completely blows L'Immortelle up. And which by the end means exactly what?

As I've said, the overall atmosphere of this film is one of horror, not unlike, actually, certain stories by Robert Aickman or Reggie Oliver, or any other classically-minded writer who sends an unwitting tourist into a world he or she can't hope to understand. Not that Turkey itself is the source of horror, but Doniol-Valcroze's character isn't depicted as wholly ignorant of the language just because. He's an easy mark for whatever it is that gets his, or their, or its, hooks into him.

A Touch of Sin (d. Jia Zhangke) - Another major 2013 film, this anthology of violent stories about China will also be arriving on Blu-ray from Kino Lorber, on April 8. Jia Zhangke loosely adapts several true events to tell the story of an angry miner (Wu Jiang) who suffers physical and mental abuse as a result of corruption in his village before finally snapping and going on a murder spree; a brutally violent thief (Baoqiang Wang); a receptionist at a sauna (Tao Zhao) who kills a man threatening her with rape; and a young man (Lanshan Luo) who is driven by financial and romantic desperation to commit suicide.

Money is at the heart of each of these stories, and the belief of the corrupt in that the ability to spend entitles them to everything they want. Now what other 2013 film does that remind you of? It's not just that, either -- coincidentally, and in pursuit of a slightly different goal, the final shot of A Touch of Sin mirrors the final shot of Martin Scorsese's The Wolf of Wall Street. But maybe not even slightly different. The final scene of The Wolf of Wall Street is set in New Zealand, which suddenly turns the target of the last shot, and the whole film, into a global one, while A Touch of Sin is a local story, top to bottom. Nevertheless, both final shots could perhaps be titles "Look At Yourselves," which is always a fair question.

A Touch of Sin is not otherwise particularly Scorsese-esque, though it, like many Scorsese films, is quite violent. This being my first Jia Zhangke film, I don't know if he's ever dealt with such extreme violence on screen before, but it does often seem like it's something he's not used to, and is constantly grappling with find new ways to make it both fresh and visceral. When the miner begins blowing people away with his shotgun, it's a shock, however easily this turn is predicted, but as Jia explores new angles from which to film it, or new tracks along which to follow the movement of bodies, it's hard to not think something more blunt and less glossily splattered might have not made his point better. If such a suspicion occurs to you, a moment later on, when Baoqiang Wang's thief approaches a man and woman outside of a bank and abruptly shoots the woman in the head, might confirm that you were correct. It's a horrible moment, not polished, seemingly not choreographed (though of course it was). One uncomfortable possibility in the change in styles is that the people the miner kills (with one exception) "have it coming" -- see also the killing of the potential rapist by Tao Zhao's receptionist. I'm not about to wring my hands over a killing done in completely justified self defense, but it's filmed in a way that is meant to remind the viewer of a martial arts or samurai film. Mind you, Jia doesn't completely flip his lid here, but the associations are unmistakable, and the design of the moment strikes me as not an entirely good idea. There are as many ways to film violence as there are to film a dream sequence, but I think filmmakers today too rarely appreciate the power of bluntness, and perhaps don't realize how even the slightest stylization can rob the moment of its slap. In A Touch of Sin, I don't think Jia Zhangke lands as many slaps as he intended.

Sunday, March 30, 2014

Tuesday, March 18, 2014

As Sane As You Or I

The last time Kino Lorber released any Pete Walker films on Blu-ray, it was in the form of a box set that included The Comeback, Die Screaming, Marianne, Schizo, and the cream of that particular crop, The House of Whipcord. I wrote about the set here, but the gist was that these are some odd films, about halfway into the realm of exploitation but never really pushing all the way. This reticence, which Walker has spoken about, could be to the film's benefit, as in The House of Whipcord, or could result in a film that barely seemed able to sit up, as with Die Screaming, Marianne. On top of all this was a whole different kind of strangeness altogether, but now's not the time to simply rewrite that post -- read it if you feel like it. The point is, today sees the release of two more Walker films by Kino through their Redemption line: The Flesh and Blood Show from 1972, and Frightmare from 1974. The range in quality on display in that earlier set is rather precisely illustrated with these titles.

To begin with The Flesh and Blood Show, well, where do I begin? The plot is simple: various young actors, all but two of whom are strangers to each other, are summoned by the promise of paying work to a once-abandoned but supposedly now up-and-running-again theater located in a small English seaside village. The show they are to put on, as the director Mike (Ray Brooks), who was summoned in the same way as the actors by the same mysterious employer, never ceases to explain, will be entirely improvised (we see a little of what they're putting together, and what they've decided on, apparently, is some kind of interpretive dance piece about cavemen). This means nothing in itself, however, and I think the improvisational nature of their show is just a short-cut by Walker and screenwriter Alfred Shaughnessy so that they can quickly move past any questions about what the play is. The play is nothing, and there is no play.

This is perhaps fitting since The Flesh and Blood Show is also nothing. The title promises two things but provides only one, and in fact much of the time it seems like Walker is using the barest bones of a horror concept as a vehicle for nudity, of which there's a fair amount. All of it gratuitous, of course -- when the three actors we meet first (played by Luan Peters, David Howey, and Judy Matheson) arrive at the theater, they see two other young actors sleeping in the stalls, and the female of the two (Penny Meredith) is topless, for no particular reason that I could find. When she wakes up and sees that she's been observed, she says "Gor blimey!" (paraphrase) and covers up. It's that sort of movie. There's also lesbian shoulder rubbing.

It's worth pointing out that these sleeping actors are initially mistaken for deceased actors, and this is the second time in about ten minutes of screen time that someone is mistakenly believed to be dead. Those instances account for nearly half of the violence in the film. The Flesh and Blood Show is almost shockingly bloodless, despite the fact that it does include a decapitation (off-screen). In an interview on the Blu-ray, Walker chalks this up to censorship, and I'm sure he's right, but because the film, specifically as a horror film, has nothing else that it especially feels like offering to its audience, it's left with nowhere to go. I should say that of course the actors start being murdered, and who the hell summoned them to this theater in the first place anyway? So you'd think that what you're getting here is a proto-slasher film, but without any slashing. And I suppose it still is a proto-slasher film in some basic ways, but there's no push to wallow in anything. I've never seen a more humdrum lesbian scene than that shoulder rubbing bit, is what I'm really upset about.

One thing that's sort of interesting about The Flesh and Blood Show, and this is another way in which it differs from slasher films, is that not every character is killed -- in fact, most of them survive. This makes it seem almost like a murder mystery, which it sort of also is, though this element of the film doesn't have any energy either. But it is sort of interesting that the body count is so low -- I can get behind that, in fact. I was reminded of the rarity of this in horror films just a couple of nights later I watched The Prowler, Joseph Zito's somewhat notorious slasher film from 1981. That movie leaves a lot of people breathing at the end, too, and in some strange way kind of feels like an attempt to correct The Flesh and Blood Show, because while the body count is low, the gore is intense. The work of Tom Savini, naturally, the violence in The Prowler is some of the most disturbing I've seen in a slasher film (hence the film's cult status, I suppose). Savini was an infernal kind of wizard back then, and his make-up effects could seem not terribly far removed from what one might conceivably imagine the real thing looking like -- what does it look like when a nude woman taking a shower is actually stabbed to death with a pitchfork? Watch The Prowler and you'll have a pretty good idea. Of course, like The Flesh and Blood Show, The Prowler is otherwise quite bad, and everyone is content to hitch their star to Savini's wagon. Pete Walker had no Savini to carry him through The Flesh and Blood Show, and we're left with a film that Walker himself admits is "safe."

Not so Frightmare, however. This one also has a very simple story, though in this case it's one with a bit more potential to have something interesting squeezed out of it. In the 1950s, a married couple are arrested, tried, and convicted of a series of cannibalistic murders. In the opening flashback, we learn that the wife was the truly Satanic one, but the husband was fully complicit in her evil, so they're both locked up in an asylum until they become sane, an outcome the judge seems to think can be guaranteed. When Frightmare's main action begins, we soon learn that about fifteen years after being locked up, the couple -- Edmund and Dorothy, played respectively by Rupert Davies and Sheila Keith -- have been deemed sane and released. They have two daughters, one grown, named Jackie (Deborah Fairfax) and one still a teenager, named Debbie (Kim Butcher) who was born while Dorothy was locked up and then put in an orphanage. Jackie and Debbie are together as the film opens, though Debbie believes her parents are dead. Jackie still sees her mom and dad, and indeed her dad does seem mentally stable. But Dorothy very much is not, and Jackie and Edmund know it. They want to stop her, even if it means tricking her, from tipping all the way back over into cannibalism. I'll tell you right now that they fail.

Frightmare is imperfect, but excellent. As is often the case with Pete Walker films, the youngsters who populate his stories are all blandly hip professionals played by actors who might be good if they were more carefully directed -- it's almost impossible to say. Though they all look different, they're all, men and women, basically the same person, more or less, at least those who aren't morally corrupt. What you also get with Frightmare, however, and which you also got with The House of Whipcord, is performances by more seasoned (older) actors. In this case, Rupert Davies, for example, is rather wonderful in a sad kind of way. You wouldn't be able to call this film a character study, whatever that means anyway, but Davies does sketch out the life of a man who found himself committing, or helping his wife commit, unspeakable acts, and you can tell that when he was convicted fifteen years ago he's the sort of person who believed his sentence was better than he deserved. Now that he's been granted a freedom he doesn't believe is his due, his only hope is to stop it from ever happening again. Very little of this is in the script, but Davies plays it.

Then you have Sheila Keith. Dorothy is the killer here, the source of horror, and she's magnificent -- she's terrifying, even, and Walker doesn't make some kind of grotesque joke out of her age (Keith wasn't elderly when she made the film, but she's one of those people who always looked older than she was) -- he simply lets go of her leash. The first scene where Keith is allowed to become fully berserk is truly chilling, a disturbing mix between "movie psycho" and the unpleasant thought that perhaps this is what being in a room with a psychopathic cannibal is really like. And she enjoys it. Keith's Dorothy loves murder, and loves sadism, and loves to eat flesh and lick human blood off her hands. It's how much Keith seems to relish it all that really turns your stomach, because while Frightmare is considerably more violent than The Flesh and Blood Show, Walker still isn't working with Tom Savini. But Savini isn't missed. Keith more than picks up the slack.

To begin with The Flesh and Blood Show, well, where do I begin? The plot is simple: various young actors, all but two of whom are strangers to each other, are summoned by the promise of paying work to a once-abandoned but supposedly now up-and-running-again theater located in a small English seaside village. The show they are to put on, as the director Mike (Ray Brooks), who was summoned in the same way as the actors by the same mysterious employer, never ceases to explain, will be entirely improvised (we see a little of what they're putting together, and what they've decided on, apparently, is some kind of interpretive dance piece about cavemen). This means nothing in itself, however, and I think the improvisational nature of their show is just a short-cut by Walker and screenwriter Alfred Shaughnessy so that they can quickly move past any questions about what the play is. The play is nothing, and there is no play.

This is perhaps fitting since The Flesh and Blood Show is also nothing. The title promises two things but provides only one, and in fact much of the time it seems like Walker is using the barest bones of a horror concept as a vehicle for nudity, of which there's a fair amount. All of it gratuitous, of course -- when the three actors we meet first (played by Luan Peters, David Howey, and Judy Matheson) arrive at the theater, they see two other young actors sleeping in the stalls, and the female of the two (Penny Meredith) is topless, for no particular reason that I could find. When she wakes up and sees that she's been observed, she says "Gor blimey!" (paraphrase) and covers up. It's that sort of movie. There's also lesbian shoulder rubbing.

It's worth pointing out that these sleeping actors are initially mistaken for deceased actors, and this is the second time in about ten minutes of screen time that someone is mistakenly believed to be dead. Those instances account for nearly half of the violence in the film. The Flesh and Blood Show is almost shockingly bloodless, despite the fact that it does include a decapitation (off-screen). In an interview on the Blu-ray, Walker chalks this up to censorship, and I'm sure he's right, but because the film, specifically as a horror film, has nothing else that it especially feels like offering to its audience, it's left with nowhere to go. I should say that of course the actors start being murdered, and who the hell summoned them to this theater in the first place anyway? So you'd think that what you're getting here is a proto-slasher film, but without any slashing. And I suppose it still is a proto-slasher film in some basic ways, but there's no push to wallow in anything. I've never seen a more humdrum lesbian scene than that shoulder rubbing bit, is what I'm really upset about.

One thing that's sort of interesting about The Flesh and Blood Show, and this is another way in which it differs from slasher films, is that not every character is killed -- in fact, most of them survive. This makes it seem almost like a murder mystery, which it sort of also is, though this element of the film doesn't have any energy either. But it is sort of interesting that the body count is so low -- I can get behind that, in fact. I was reminded of the rarity of this in horror films just a couple of nights later I watched The Prowler, Joseph Zito's somewhat notorious slasher film from 1981. That movie leaves a lot of people breathing at the end, too, and in some strange way kind of feels like an attempt to correct The Flesh and Blood Show, because while the body count is low, the gore is intense. The work of Tom Savini, naturally, the violence in The Prowler is some of the most disturbing I've seen in a slasher film (hence the film's cult status, I suppose). Savini was an infernal kind of wizard back then, and his make-up effects could seem not terribly far removed from what one might conceivably imagine the real thing looking like -- what does it look like when a nude woman taking a shower is actually stabbed to death with a pitchfork? Watch The Prowler and you'll have a pretty good idea. Of course, like The Flesh and Blood Show, The Prowler is otherwise quite bad, and everyone is content to hitch their star to Savini's wagon. Pete Walker had no Savini to carry him through The Flesh and Blood Show, and we're left with a film that Walker himself admits is "safe."

Not so Frightmare, however. This one also has a very simple story, though in this case it's one with a bit more potential to have something interesting squeezed out of it. In the 1950s, a married couple are arrested, tried, and convicted of a series of cannibalistic murders. In the opening flashback, we learn that the wife was the truly Satanic one, but the husband was fully complicit in her evil, so they're both locked up in an asylum until they become sane, an outcome the judge seems to think can be guaranteed. When Frightmare's main action begins, we soon learn that about fifteen years after being locked up, the couple -- Edmund and Dorothy, played respectively by Rupert Davies and Sheila Keith -- have been deemed sane and released. They have two daughters, one grown, named Jackie (Deborah Fairfax) and one still a teenager, named Debbie (Kim Butcher) who was born while Dorothy was locked up and then put in an orphanage. Jackie and Debbie are together as the film opens, though Debbie believes her parents are dead. Jackie still sees her mom and dad, and indeed her dad does seem mentally stable. But Dorothy very much is not, and Jackie and Edmund know it. They want to stop her, even if it means tricking her, from tipping all the way back over into cannibalism. I'll tell you right now that they fail.

Frightmare is imperfect, but excellent. As is often the case with Pete Walker films, the youngsters who populate his stories are all blandly hip professionals played by actors who might be good if they were more carefully directed -- it's almost impossible to say. Though they all look different, they're all, men and women, basically the same person, more or less, at least those who aren't morally corrupt. What you also get with Frightmare, however, and which you also got with The House of Whipcord, is performances by more seasoned (older) actors. In this case, Rupert Davies, for example, is rather wonderful in a sad kind of way. You wouldn't be able to call this film a character study, whatever that means anyway, but Davies does sketch out the life of a man who found himself committing, or helping his wife commit, unspeakable acts, and you can tell that when he was convicted fifteen years ago he's the sort of person who believed his sentence was better than he deserved. Now that he's been granted a freedom he doesn't believe is his due, his only hope is to stop it from ever happening again. Very little of this is in the script, but Davies plays it.

Then you have Sheila Keith. Dorothy is the killer here, the source of horror, and she's magnificent -- she's terrifying, even, and Walker doesn't make some kind of grotesque joke out of her age (Keith wasn't elderly when she made the film, but she's one of those people who always looked older than she was) -- he simply lets go of her leash. The first scene where Keith is allowed to become fully berserk is truly chilling, a disturbing mix between "movie psycho" and the unpleasant thought that perhaps this is what being in a room with a psychopathic cannibal is really like. And she enjoys it. Keith's Dorothy loves murder, and loves sadism, and loves to eat flesh and lick human blood off her hands. It's how much Keith seems to relish it all that really turns your stomach, because while Frightmare is considerably more violent than The Flesh and Blood Show, Walker still isn't working with Tom Savini. But Savini isn't missed. Keith more than picks up the slack.

Monday, March 17, 2014

The Mind of God

It occurred to me recently that if you wanted to make a particularly strong case for the auteur theory, you might want to look at documentary filmmakers. Or rather, my thinking went like this: If you wanted to make a strong case for the auteur theory, what about looking at documentary filmmakers? Oh because most of them are stylistically and artistically barren. Because the auteur theory isn't supposed to have anything to do with rhetoric or activism, the pool of documentarians to which you could beneficially -- for you or them -- apply it is a shrinking one. Maybe hasn't always been, but is now. When you think about it, though, documentary filmmakers are hemmed in by facts, if they're honest and ethical (and the pool grows ever smaller) so that the only way they can really distinguish themselves is through a creative, artistic point of view. Still, the great non-fiction (a dicey term, which is another thing, but never mind) filmmakers don't often find themselves roped into that debate, and they should be. Or some should be. Or one should be.

In 1978, Errol Morris released his first film, the documentary Gates of Heaven, about pet cemeteries in Napa Valley. Roger Ebert flipped his damn lid for the movie, and rightly so, and this reaction by the world's most popular film critic no doubt helped this strange, quietly breathtaking piece of work, which could very uncharitably, blindly, and myopically be described as a collection of talking head interviews, not actually fall of the edge of the Earth. I watched Gates of Heaven the other night, having not seen it in years, and among the many things that are striking about it is that even then, even before his major breakthrough film, The Thin Blue Line from 1988, and even before Morris's invention of the Interretron, a rough description of which would paint it as a camera attachment that allows Morris and his interview subject to view each other through separate camera lenses so that the speaker, Morris's subject, is talking to Morris but looking directly into the camera, even before all of this, his style was intact. In terms of the kinds of things held within the frame, Gates of Heaven really doesn't offer much; most of it really does consist of a speaker, or speakers, positioned in the middle of the frame. There are very few scenes that even call for cutting from one speaker to another (I can think of one such scene, a partial pet funeral that appears maybe halfway through the film), and with one or two notable exceptions I don't think the camera ever moves. Yet somehow out of this -- and certainly with the help of the unique subjects Morris seems to have an unerring skill for turning up -- and in just over 80 minutes, he created a sort of whispering philosophical epic about pets and pet cemeteries (literally -- Morris is too smart and too curious to use them only as a metaphor), the 1970s, naiveté, insensitivity, sensitivity, mortality, and, frankly, just loads more. Gates of Heaven is a very direct film in some ways -- the way in which it is so very much about the 1970s, and the burgeoning self-help culture, and how the children of the 60s and 70s were not the same kind of people as their parents, comes through very strongly. However as the film fades out, there is a lingering mystery to it, a sense that for all a given audience may have understood, and may have "gotten" about it, there are still depths that have been plumbed by Morris but perhaps not yet by us. And though I'm not here today to talk much more about Gates of Heaven, my own theory is that the source of this exhilarating uncertainty is, in fact, the pets. The silent montage of pet headstones near the end seems to change everything. Why? Because, maybe, it's a reminder that everything else you've now got on your mind because of this film started here.

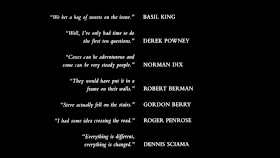

So that was his first film. How did Morris do it? Well, as implied above, by seemingly doing nothing. But of course that can't be it, can it? I'll tell you, though, the movie that's my ostensible subject here, offers another example of his mysterious genius. That film is A Brief History of Time, Morris's film about Stephen Hawking from 1991, and his follow up to The Thin Blue Line. There are a lot of standard documentary tools that Morris likes to dispense with -- not every time out, but when it suits him, at least -- and one of those tools is chyrons, which are the on-screen graphics that tell you who a speaker is. I'm talking about Harlan Ellison again or how much I hate Bonnie and Clyde again, and under my fat head it says "BILL RYAN, THINKER" or whatever. A useful tool, one must admit, but if Morris can get by without them, he will -- he does in Gates of Heaven, but through context, and because people keep talking about each other, the viewer can figure it out. But in A Brief History of Time there are a whole lot more speakers than there are in Gates of Heaven, and all of them are talking about one of two things, and often both at once: black holes, and Stephen Hawking. So while it might be easy to figure out who Hawking's mother and sister are by what they're saying, his various classmates from Oxford and Cambridge, for instance, are rather harder to place a name to. It doesn't matter a great deal -- again, Hawking is the film's subject, and their's as well -- but you do still kind of wonder. Then the movie ends and the credits roll, and we get a list of the speakers, credited beside -- and this is the kicker -- one of their quotes from the film. Like so:

Now, I don't know what anyone else's experience with this has been, but when I read those quotes I immediately was able to place the words to a face. It could be that this was achieved by the film simply being well edited, by which I mean all the good stuff was left in and the bad stuff was taken out, but it still feels a little bit like a magic trick. "How did he know I'd remember that phrase?" Or maybe because this film is also just about 80 minutes and my memory's not as devastated as I sometimes think it is. Morris is still taking a lot on faith, or putting a lot of it into his audience.

A Brief History of Time, I should probably point out, has been the "lost" Morris film just about since it's release. For whatever reason, while everything else he's made, including more obscure movies like Vernon, Florida, has been more or less readily available, A Brief History of Time never got a standard DVD release, and in this interview with The Dissolve, Morris describes his quest to buy it back and then working with Criterion to have it added to their collection. Which is why we find ourselves here today, with the Criterion release happening tomorrow. Pardon my frank enthusiasm, but this is a wonderful thing in general, and a wonderfully put together release. An adaptation of Stephen Hawking's physics text/memoir (which I confess with much chagrin I've never read) of the same name, in A Brief History of Time Morris juxtaposes biographical material, usually delivered by Hawking's friends, family, and colleagues, with Hawking speaking about his work, his scientific philosophy, as well as the history of black hole theory, in the development of which Hawking played a key role.

Which will have to do for a plot summary. Visually, Morris gets away from the strict talking head aesthetic -- and it is an aesthetic, at least the way he does it -- that he'd already gotten away from anyway with The Thin Blue Line, and, in the way that earlier "true crime" film employed reenactments of the murder of a Dallas police officer to make a case for the innocence of the man who was convicted and against the man who turned out to actually be guilty, sort of "reenacts" classic metaphors (the chicken and the egg) and those original to Hawking (a shattering teacup) to illustrate quite abstract scientific concepts. And when photographing his interview subjects, with the indispensable assistance of cinematographer John Bailey, Morris goes deeply, and perhaps wryly, British. Almost everybody, except Hawking's family and one or two others, is just on the edge, and sometimes partly within, a kind of dim, leathery shadow -- no one is shown smoking a pipe but you can smell one anyway. Even if this is only a depiction of what the environments that housed scientific debates in Cambridge, Oxford, and elsewhere in the UK some fifty years ago might look like only in the current popular imagination, it nevertheless, as aesthetic choices that concern themselves with the past must do, makes it all feel immediate -- the exhilaration of discovery, even one that may later be disproved, somehow comes through the words of these pleasant but reserved men because something about the visuals puts us there. That, and of course the structure of the storytelling, the easily skilled storytelling by both Morris and his subjects, and the fact that this giant is sitting apart, shrunken and rendered immobile by his debilitating disease, his mind so breathtakingly dextrous that his distance from everyone else in the film puts him not just on another street, as one former classmate of Hawking says of him with great reverence, but another planet.

"He liked dancing, you see," Hawking's aunt says at one point, speaking of the scientist as he existed before the effects of ASL changed his life. Morris shows us photographs of this other young man, and while they're plainly the same person it can still be hard to reconcile these pictures with the famous scientist we all know. Morris lets this disconnect and lines like those spoken by his aunt just sit and accumulate so that along with everything else A Brief History of Time is, it's also quite melancholy. Melancholy, though never pitying -- not that it could be expected to be the latter, because what a boneheaded misstep that would have been, but it would be hard to watch the film and not walk away from it feeling both sad and humbled. Stories told about Hawking's early symptoms and eventual diagnosis, not to mention the initial prognosis that he would only live another year and a half -- this being told to him over fifty years ago now -- feel horrifying even todau, the intense focus that his never-weakened mind was finally able to summon still bewildering. But while Hawking's mother does speculate that his ASL allowed him to work harder than he might have had he not had the disease, she is quick to dismiss the notion that it could ever be considered any kind of blessing. This is the strange nature of Stephen Hawking as a public figure, that we might consider and wonder about but never understand. That Morris does not use his film to pretend to find an answer to Hawking's full and deepest thinking about his situation is not only as it should be, but it's in keeping with the rest of his work, and Hawking's. At different times in the film, Hawking points out where Einstein was wrong, as well as where his own theories have been mistaken. Nothing is ever certain, including a healthy life.

A Brief History of Time is the first of Morris's two science documentaries, the other being 1997's Fast, Cheap & Out of Control, which juggles the stories of four disparate men with four disparate jobs -- a lion tamer, a topiary gardener, an expert on naked mole rats, and an MIT scientist who builds robots. That film, which wonders about our relationship to animals (like Gates of Heaven) and the, when you think about it, resemblance of so much in life, including our own bodies, to insects, finds the cosmic here on Earth. Even the topiary gardener, as shot by Morris and DP Robert Richardson, seems to be creating an alien environment that we're as yet incapable of fully understanding. The fact that he's doing this by manipulating flora to look like fauna, and that this is juxtaposed with images of artificial life in the form of the MIT scientist's (insect-like, it should be noted) robots, with mammals that behave like insects, and with lions who have been trained to entertain us and thereby actually resemble us, well, it's a lot to take in. And this is Morris actually scaling back from A Brief History of Time, at least in terms of scope. But going earthbound only serves to show how little we understand about what we do and see every day, and by the way at this point in his career Morris's Interrotron was in full working order, so this new tweak to his style adds a shot of surrealism -- these people on screen are looking right at me -- that is somehow both a gimmick and yet wholly unfeigned. It's an honest gimmick that makes the way a person looks at you when they're talking to you appear off-kilter. So basically Morris drags us back down to Earth and suddenly that's when things go crazy. That film seems to ask the question "What the hell are we, anyway?" Meanwhile, in A Brief History of Time, so much is unsolvable, or anyway unsolved, the questions and goals of Hawking and his fellow scientists so overwhelmingly massive, but it's all rooted in Hawking's life and humanity, that the result is a kind of drifting, general feeling that we're all in this together -- we don't know what this is about, but one day we will. The last shot of the film is of the back of Hawking's wheelchair, which is superimposed over a field of stars, the idea being that Hawking is facing and moving towards those stars. As an image in an Errol Morris film it's perhaps a little bit on the nose, but so little else in his career has been that just one can't hurt.

In 1978, Errol Morris released his first film, the documentary Gates of Heaven, about pet cemeteries in Napa Valley. Roger Ebert flipped his damn lid for the movie, and rightly so, and this reaction by the world's most popular film critic no doubt helped this strange, quietly breathtaking piece of work, which could very uncharitably, blindly, and myopically be described as a collection of talking head interviews, not actually fall of the edge of the Earth. I watched Gates of Heaven the other night, having not seen it in years, and among the many things that are striking about it is that even then, even before his major breakthrough film, The Thin Blue Line from 1988, and even before Morris's invention of the Interretron, a rough description of which would paint it as a camera attachment that allows Morris and his interview subject to view each other through separate camera lenses so that the speaker, Morris's subject, is talking to Morris but looking directly into the camera, even before all of this, his style was intact. In terms of the kinds of things held within the frame, Gates of Heaven really doesn't offer much; most of it really does consist of a speaker, or speakers, positioned in the middle of the frame. There are very few scenes that even call for cutting from one speaker to another (I can think of one such scene, a partial pet funeral that appears maybe halfway through the film), and with one or two notable exceptions I don't think the camera ever moves. Yet somehow out of this -- and certainly with the help of the unique subjects Morris seems to have an unerring skill for turning up -- and in just over 80 minutes, he created a sort of whispering philosophical epic about pets and pet cemeteries (literally -- Morris is too smart and too curious to use them only as a metaphor), the 1970s, naiveté, insensitivity, sensitivity, mortality, and, frankly, just loads more. Gates of Heaven is a very direct film in some ways -- the way in which it is so very much about the 1970s, and the burgeoning self-help culture, and how the children of the 60s and 70s were not the same kind of people as their parents, comes through very strongly. However as the film fades out, there is a lingering mystery to it, a sense that for all a given audience may have understood, and may have "gotten" about it, there are still depths that have been plumbed by Morris but perhaps not yet by us. And though I'm not here today to talk much more about Gates of Heaven, my own theory is that the source of this exhilarating uncertainty is, in fact, the pets. The silent montage of pet headstones near the end seems to change everything. Why? Because, maybe, it's a reminder that everything else you've now got on your mind because of this film started here.

So that was his first film. How did Morris do it? Well, as implied above, by seemingly doing nothing. But of course that can't be it, can it? I'll tell you, though, the movie that's my ostensible subject here, offers another example of his mysterious genius. That film is A Brief History of Time, Morris's film about Stephen Hawking from 1991, and his follow up to The Thin Blue Line. There are a lot of standard documentary tools that Morris likes to dispense with -- not every time out, but when it suits him, at least -- and one of those tools is chyrons, which are the on-screen graphics that tell you who a speaker is. I'm talking about Harlan Ellison again or how much I hate Bonnie and Clyde again, and under my fat head it says "BILL RYAN, THINKER" or whatever. A useful tool, one must admit, but if Morris can get by without them, he will -- he does in Gates of Heaven, but through context, and because people keep talking about each other, the viewer can figure it out. But in A Brief History of Time there are a whole lot more speakers than there are in Gates of Heaven, and all of them are talking about one of two things, and often both at once: black holes, and Stephen Hawking. So while it might be easy to figure out who Hawking's mother and sister are by what they're saying, his various classmates from Oxford and Cambridge, for instance, are rather harder to place a name to. It doesn't matter a great deal -- again, Hawking is the film's subject, and their's as well -- but you do still kind of wonder. Then the movie ends and the credits roll, and we get a list of the speakers, credited beside -- and this is the kicker -- one of their quotes from the film. Like so:

Now, I don't know what anyone else's experience with this has been, but when I read those quotes I immediately was able to place the words to a face. It could be that this was achieved by the film simply being well edited, by which I mean all the good stuff was left in and the bad stuff was taken out, but it still feels a little bit like a magic trick. "How did he know I'd remember that phrase?" Or maybe because this film is also just about 80 minutes and my memory's not as devastated as I sometimes think it is. Morris is still taking a lot on faith, or putting a lot of it into his audience.

A Brief History of Time, I should probably point out, has been the "lost" Morris film just about since it's release. For whatever reason, while everything else he's made, including more obscure movies like Vernon, Florida, has been more or less readily available, A Brief History of Time never got a standard DVD release, and in this interview with The Dissolve, Morris describes his quest to buy it back and then working with Criterion to have it added to their collection. Which is why we find ourselves here today, with the Criterion release happening tomorrow. Pardon my frank enthusiasm, but this is a wonderful thing in general, and a wonderfully put together release. An adaptation of Stephen Hawking's physics text/memoir (which I confess with much chagrin I've never read) of the same name, in A Brief History of Time Morris juxtaposes biographical material, usually delivered by Hawking's friends, family, and colleagues, with Hawking speaking about his work, his scientific philosophy, as well as the history of black hole theory, in the development of which Hawking played a key role.

Which will have to do for a plot summary. Visually, Morris gets away from the strict talking head aesthetic -- and it is an aesthetic, at least the way he does it -- that he'd already gotten away from anyway with The Thin Blue Line, and, in the way that earlier "true crime" film employed reenactments of the murder of a Dallas police officer to make a case for the innocence of the man who was convicted and against the man who turned out to actually be guilty, sort of "reenacts" classic metaphors (the chicken and the egg) and those original to Hawking (a shattering teacup) to illustrate quite abstract scientific concepts. And when photographing his interview subjects, with the indispensable assistance of cinematographer John Bailey, Morris goes deeply, and perhaps wryly, British. Almost everybody, except Hawking's family and one or two others, is just on the edge, and sometimes partly within, a kind of dim, leathery shadow -- no one is shown smoking a pipe but you can smell one anyway. Even if this is only a depiction of what the environments that housed scientific debates in Cambridge, Oxford, and elsewhere in the UK some fifty years ago might look like only in the current popular imagination, it nevertheless, as aesthetic choices that concern themselves with the past must do, makes it all feel immediate -- the exhilaration of discovery, even one that may later be disproved, somehow comes through the words of these pleasant but reserved men because something about the visuals puts us there. That, and of course the structure of the storytelling, the easily skilled storytelling by both Morris and his subjects, and the fact that this giant is sitting apart, shrunken and rendered immobile by his debilitating disease, his mind so breathtakingly dextrous that his distance from everyone else in the film puts him not just on another street, as one former classmate of Hawking says of him with great reverence, but another planet.

"He liked dancing, you see," Hawking's aunt says at one point, speaking of the scientist as he existed before the effects of ASL changed his life. Morris shows us photographs of this other young man, and while they're plainly the same person it can still be hard to reconcile these pictures with the famous scientist we all know. Morris lets this disconnect and lines like those spoken by his aunt just sit and accumulate so that along with everything else A Brief History of Time is, it's also quite melancholy. Melancholy, though never pitying -- not that it could be expected to be the latter, because what a boneheaded misstep that would have been, but it would be hard to watch the film and not walk away from it feeling both sad and humbled. Stories told about Hawking's early symptoms and eventual diagnosis, not to mention the initial prognosis that he would only live another year and a half -- this being told to him over fifty years ago now -- feel horrifying even todau, the intense focus that his never-weakened mind was finally able to summon still bewildering. But while Hawking's mother does speculate that his ASL allowed him to work harder than he might have had he not had the disease, she is quick to dismiss the notion that it could ever be considered any kind of blessing. This is the strange nature of Stephen Hawking as a public figure, that we might consider and wonder about but never understand. That Morris does not use his film to pretend to find an answer to Hawking's full and deepest thinking about his situation is not only as it should be, but it's in keeping with the rest of his work, and Hawking's. At different times in the film, Hawking points out where Einstein was wrong, as well as where his own theories have been mistaken. Nothing is ever certain, including a healthy life.

A Brief History of Time is the first of Morris's two science documentaries, the other being 1997's Fast, Cheap & Out of Control, which juggles the stories of four disparate men with four disparate jobs -- a lion tamer, a topiary gardener, an expert on naked mole rats, and an MIT scientist who builds robots. That film, which wonders about our relationship to animals (like Gates of Heaven) and the, when you think about it, resemblance of so much in life, including our own bodies, to insects, finds the cosmic here on Earth. Even the topiary gardener, as shot by Morris and DP Robert Richardson, seems to be creating an alien environment that we're as yet incapable of fully understanding. The fact that he's doing this by manipulating flora to look like fauna, and that this is juxtaposed with images of artificial life in the form of the MIT scientist's (insect-like, it should be noted) robots, with mammals that behave like insects, and with lions who have been trained to entertain us and thereby actually resemble us, well, it's a lot to take in. And this is Morris actually scaling back from A Brief History of Time, at least in terms of scope. But going earthbound only serves to show how little we understand about what we do and see every day, and by the way at this point in his career Morris's Interrotron was in full working order, so this new tweak to his style adds a shot of surrealism -- these people on screen are looking right at me -- that is somehow both a gimmick and yet wholly unfeigned. It's an honest gimmick that makes the way a person looks at you when they're talking to you appear off-kilter. So basically Morris drags us back down to Earth and suddenly that's when things go crazy. That film seems to ask the question "What the hell are we, anyway?" Meanwhile, in A Brief History of Time, so much is unsolvable, or anyway unsolved, the questions and goals of Hawking and his fellow scientists so overwhelmingly massive, but it's all rooted in Hawking's life and humanity, that the result is a kind of drifting, general feeling that we're all in this together -- we don't know what this is about, but one day we will. The last shot of the film is of the back of Hawking's wheelchair, which is superimposed over a field of stars, the idea being that Hawking is facing and moving towards those stars. As an image in an Errol Morris film it's perhaps a little bit on the nose, but so little else in his career has been that just one can't hurt.

Monday, March 3, 2014

It's Cold Out There Every Day

[This post contains spoilers for The Ice Harvest as well as Groundhog Day, but you've all seen the latter anyway]

Shortly after seeing Harold Ramis's The Ice Harvest in 2006, something occurred to me. Before I tell you what that something is, I should note that The Ice Harvest, a somewhat neglected entry in the late Ramis's filmography, is a favorite of mine, and when Ramis died on February 24 it was the first movie I thought to watch in his honor. If you haven't seen it, I highly recommend that you take care of this as soon as you possibly can, and once you have perhaps you, too, will find something occurring to you. And that something is that The Ice Harvest in many ways closely resembles, and in fact functions as a sort of inverted restating of, Ramis's beloved 1993 masterpiece Groundhog Day.

In Groundhog Day, to catch you up, Bill Murray plays Phil Connors a cynical and intensely arrogant Pittsburgh weatherman who, as the film begins, is begrudgingly making his annual trip to Punxsutawney, PA to cover the Groundhog Day ceremony, which involves the removing of Punxsutawney Phil, groundhog, from a hole and announcing his prognostication regarding how many more weeks of winter we will or will not have. So with his his cameraman Larry (Chris Elliott) and his producer Rita (Andie MacDowell) in tow, Phil, weatherman, goes there and in general acts like a big-city asshole. However, his prediction that a blizzard will not hit the area turns out to be wrong, and Phil realizes he's snowed in, in Punxsutawney. The next morning, he wakes up to the same sounds and sights and conversations he'd had the morning before. He's freaked out, but just tries to roll with it, until it happens again the next morning. And again and again and again.

So that's the premise. In The Ice Harvest, John Cusack plays Charlie Arglist, a mob lawyer in Wichita, KS who, on Christmas Eve, and during a terrible ice storm, and with Vic Cavanaugh (Bill Bob Thornton), his pornographer colleague -- "friend" seems too strong -- has just robbed Bill Guerrard (Randy Quaid), Wichita's reigning mob boss. The ice storm has made it impossible for the men to skip town as expeditiously as they'd like, so they have no choice but to wait it out. As it happens, though, "waiting it out" ends up involving Charlie nursing the love he has for Renata (Connie Nielsen), who owns the strip club Charlie frequents, and therefore choosing to help her blackmail a local politician. Charlie also spends a lot of time escorting his drunk friend Pete (Oliver Platt), who is unhappily married to Charlie's ex-wife. Charlie also spends a lot of time afraid that Roy Gelles (Mike Starr), one of Guerrard's thugs, is on to the robbery, and communicating (in person, since he slipped on the ice and broke his cell phone) with an aggravated Vic, to see what should be done about this. And so on and so on.

Now, those two summaries may not seem to you to offer up a lot of similarities, but I do hope you'll have noticed on theme joining the two, which is the inability to escape an unhappy situation due to inclement weather -- this is sort of key. A blizzard keeps Phil Connors locked into this fantasy zone of Punxsutawney (let's just say that Punxsutawney is magical and that's why this happened) and so forces him to relive the same day over and over again. One of the many ingenious aspects of Groundhog Day is the logical progression of Phil's attitude towards his situation. First, he's frightened, but soon he sees the potential to take advantage of every selfish, even borderline sociopathic, impulse his natural personality has ever entertained, and without consequence. But when one of those impulses -- to seduce Rita by using what he's learned about her over the course of possibly hundreds of conversations with her that he remembers but which she doesn't -- leads him to fall in love with her, only to start from zero the next morning, an existential despair takes hold and he turns to suicide. Which doesn't work.

The Ice Harvest, meanwhile, begins with Charlie in the grip of existential despair. He's about at the point Phil is after maybe suicide attempt number three, though without the "let's throw this at the wall and see what sticks" attitude Phil is able to bring to his attempts, Charlie is content to simply do something that many people would only consider suicidal, which is, he rips off a violent mob boss. He hopes it will free him from the clutches of his miserable, amoral existence, but while the fear of death is a key motivator of Charlie's actions throughout the film, its not unreasonable to think that somewhere in his subconscious his thinking is "No matter how this ends up, I'm out." What's great about the character of Charlie Arglist is that he's a miserable shit of a human being who knows exactly what he is and hates himself. By the time we meet him, most of the miserable shittiness he's ever done in his life has already been done, but the regret of it all hangs like death over him, and lives in Cusack's face (this is Cusack's best performance, as far as I'm concerned). Now he wants to start from scratch, as Phil does every morning, or barring that, to die.

So, picking up with Groundhog Day, Phil's inability to kill himself flips a switch in his mind and he begins a new phase. He begins to learn things, to not behave selfishly, to help prevent as many of the big and small mishaps that he has by now learned will transpire over the course of one February 2 in Punxsutawney (the fact that he can't prevent the death of an elderly homeless man, no matter how hard he tries, is perhaps one of the many nods by Ramis to his own self-defined "Budd-ish"-ness). In short, he starts to become a better person. I put the bit about Ramis being "Budd-ish" in parentheses, but of course it's more than a parenthetical in Groundhog Day, as each new day is sort of a new life, and as he goes along his wisdom expands, his self-absorption drains away, and he becomes the shining light of Punxsutawney.

Of course, this doesn't quite happen to Charlie Arglist, but some version of it does. As his night wears on, Charlie witnesses, and even takes part in, some horrendous things. He has associated himself, willingly, with murderers. He disposes of corpses. He sees people die. He kills people (he sort of has to, but the Buddhists would frown on it anyway). Pete, who is maybe his best friend, is a drunken lout. In all honesty, the film tries to let Charlie off the hook a little bit regarding his ex-wife by giving evidence that she's no prize, but they don't let him off the hook regarding his kids, who have clearly suffered because of him, and on top of that, when Charlie and Pete blunder into Pete's home in the middle of a Christmas Eve dinner with the in-laws, Pete's father-in-law offers the two of them a pretty strong and utterly fair rebuke. Pete behaves appallingly, drunk and boorish and profane, no matter how unpleasant his wife, Charlie's ex, is, because she ain't the only one sitting down to dinner. Anyway, so this is Charlie's friend. And as this all plays out, the horrors of Charlie's Christmas Eve, Charlie's disgust, with himself and others, continues to boil. Like Phil, he breaks through the awfulness. Phil becomes a wonderful person, and Charlie becomes, at best, an acceptable person. In Groundhog Day, as things get better for Phil, Phil gets better. In The Ice Harvest, Charlie gets better as things get worse for him. By the end of Groundhog Day Phil has helped out pretty much everybody in town. The last thing Charlie does before finally getting out of Wichita is to help the strip club's bartender, who's trying to take his family to Six Flags, siphon some of his gas. It's something, anyway.

Phil's endless loop finally ends, and February 2 turns into February 3. There's no literal time loop in The Ice Harvest, but the film has sort of a motto that implies a metaphorical, or maybe linguistic, or anyway thematically appropriate if somewhat mysterious version. It's first seen written as graffiti above a urinal in the strip club men's room (curiously appropriate) and it says "As Wichita Falls, so falls Wichita Falls." At first glance it almost seems like the phrase is eating its own tail, but of course it isn't -- there's a way out of it. It also implies a sort of crumbling, of big things, everything, crashing down around your ears. But there's still a way out of it. The temperature warms up, the ice thaws, the roads clear, and you and your hungover friend can drive away from the ruins.